Al-Qaeda Remains the World’s Most Dangerous Terrorist Group 24 Years After 9/11

Twenty-four years after the devastating attacks of September 11, 2001, which claimed 2,977 innocent lives, al-Qaeda continues to represent the most significant terrorist threat globally, according to counterterrorism expert Bill Roggio. Despite the emergence of groups like ISIS and Hamas that have captured international attention through their brutal tactics, Roggio, a senior editor at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies’ “Long War Journal,” warns that al-Qaeda’s reach and capabilities have actually expanded since that fateful day. “The situation there is far worse than it was pre-9/11,” he explains, pointing to the Taliban’s support in Afghanistan where al-Qaeda now operates training camps in at least 13 of the country’s 34 provinces. This territorial expansion isn’t limited to Afghanistan—the group has established footholds across the Middle East and Africa, controlling more than a third of Somalia, while its affiliates have gained significant power in Syria through organizations like Hayat Tahrir al-Sham.

The most alarming development in global terrorism is the proliferation of safe havens where these groups can operate with minimal interference. These protected spaces provide terrorist organizations the critical resources they need: time, security, and space to plot attacks, execute operations, recruit new members, and raise funds. Afghanistan has once again become such a haven for al-Qaeda, while Iran continues to offer sanctuary to various terrorist groups. In Iraq, Shia militias operate with virtual impunity, and in Somalia, al-Shabaab (an al-Qaeda branch) controls significant territory. The danger of these safe havens cannot be overstated—they create the precise conditions that enabled the planning and execution of attacks like 9/11. Most concerning to security experts is that these secure operational bases now exist in multiple locations worldwide, multiplying the threat exponentially.

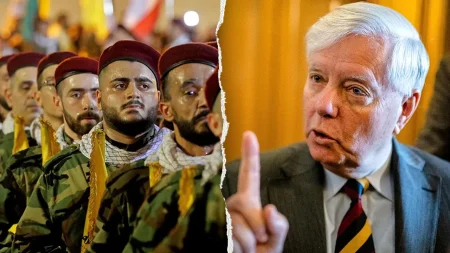

The evolution of terrorist capabilities presents another layer of concern. Groups like Hamas, Hezbollah, and the Houthis now have access to increasingly sophisticated weapons through state sponsorship, particularly from Iran. Additionally, technological advancements have democratized tools of destruction—commercially available drones and artificial intelligence capabilities are now within reach of terrorist organizations. However, Roggio emphasizes that advanced technology isn’t necessarily required to inflict massive harm: “Nobody thought that box cutters and some training on airlines would lead to 9/11 and yet it happened.” This sobering reminder highlights how seemingly simple tools, combined with planning and determination, can result in catastrophic attacks. The terrorist landscape has transformed dramatically since 2001, with groups that either didn’t exist or operated as small cells before 9/11 now commanding “armies across the globe.”

Perhaps most troubling is the shift in public attitudes toward extremist organizations. Roggio points to increasing support for groups like Hamas in some quarters and rising antisemitism as indicators that “things are trending for the jihadist organizations.” This normalization of extremist ideologies represents a fundamental challenge in the fight against terrorism—one that cannot be addressed through military means alone. “To me, these are indications that we have lost the war on terror,” Roggio states bluntly. The expert argues that there’s a collective lack of will to confront the root causes of extremism and develop comprehensive strategies to counter radical ideologies. Without addressing both the operational capabilities and the ideological underpinnings of terrorist groups, the threat will continue to evolve and expand.

The comparison to historical conflicts underscores the nature of the challenge. “We defeated Nazi Germany,” Roggio notes. “It’s something that can be done. We had the will to do it.” This historical parallel highlights what Roggio sees as a crucial missing element in current counterterrorism efforts—the collective determination to confront the threat comprehensively. Our hesitation and inconsistent commitment have, in his view, only emboldened terrorist organizations and their state sponsors. The growth of terrorist networks from cellular structures to global movements with territorial control demonstrates how this lack of resolve has allowed extremist groups to flourish in the decades since 9/11. What began as an operation by 19 al-Qaeda operatives has expanded into multiple terrorist organizations with international reach and increasingly sophisticated capabilities.

Looking forward, Roggio outlines the necessary approach to effectively counter terrorism: “Until we remove the state sponsorship, until we are able to effectively deal with the purveyors of the radical ideology, these threats will persist.” This assessment points to a dual challenge—confronting both the material support provided by states like Iran and addressing the ideological foundations that fuel extremism. The evolution of terrorist threats over the past two decades demonstrates that military action alone cannot resolve this complex problem. Instead, a multi-faceted approach that combines targeted operations against terrorist infrastructure with concerted efforts to counter extremist ideologies and deny safe havens is essential. Twenty-four years after the attacks that changed America and the world, the threat of terrorism remains—transformed but undiminished, requiring renewed commitment and strategic vision to combat effectively.