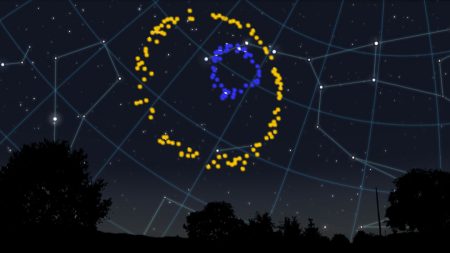

The Milky Way is home to one of the most massive and ancient objects in the universe, the supermassive black hole at its heart, Sgr A. This black hole, located approximately 26,000 light-years from Earth, represents a portion of the galactic center that is about 4 million times as dense as the Sun. It is the most massive and luminous supermassive object known, making it a focal point for current astronomical curiosity. Researchers have recently made remarkable strides in understanding Sgr A through specialized observations and advanced telescopes, as seen through the workshop’s excerpt.

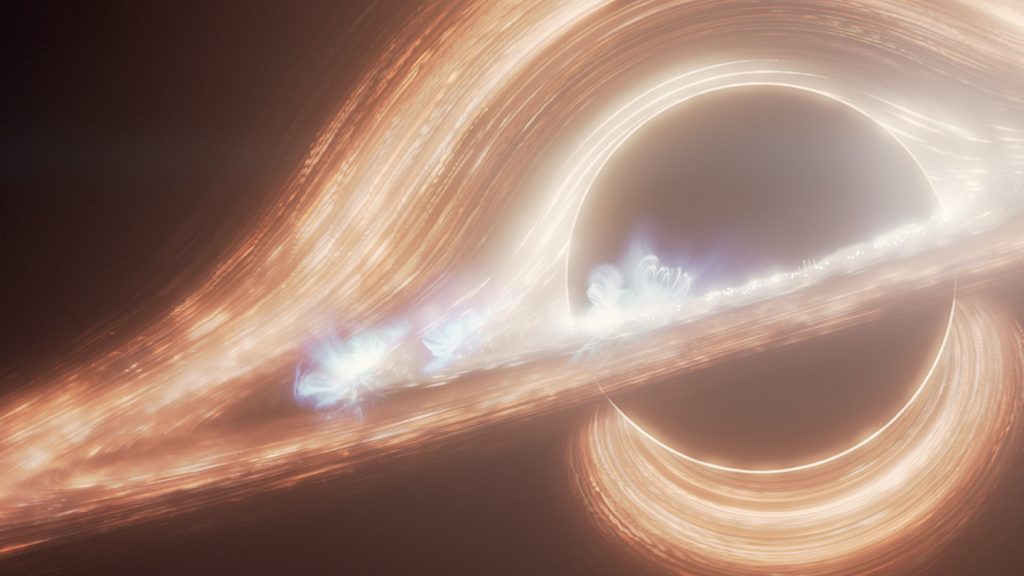

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), launched in April 2023, has been transmitting crucial data about Sgr A for over a year. Earlier surveys, including the first direct image of the black hole, suggested that its accretion disk, a thick sphere of plasma surrounding it, flickered faintly every few seconds or minutes. These observations were obtained through concentrated continuous exposure periods of more than two years, culminating in the most extensive mapping yet of Sgr A. The team has observed this phenomenon for 102 nights, capturing the periodic fluctuations in the disk’s brightness.

As detailed by astrophysicist Farhad Yusef-Zadeh of the Northwestern University Evanston Research Insitute, the disk of Sgr A* exhibits a characteristic pattern of activity. While the disk generally remains relatively quiet, its intensity spikes are strikingly instantaneous—every few seconds or minutes, a seemingly bright flash erupts. Yusef-Zadeh notes that these bursts occur at random times despite the magnetic structure of the accretion disk. "The gaps between bursts could be anything from minutes to years," he states. The variability in the disk’s brightness provides critical insight into the physics multiplying at this enigmatic object.

The Advanced versions of JWST enable unprecedented capabilities for observing Sgr A*. Unlike ground-based telescopes, which face Earth and thus lack the optimal conditions for capturing the vast, expanding space-like light beams from the disk, JWST can achieve minimum contrast by orbiting the Sun in an almost shadowless region of the solar system. This provides an ideal environment for capturing the light modulations and effectively capturing a full 24-hour observation window— aquac optics noted in a previous excerpt. The team has requested a full 24 hours of continuous observation, which will be used to assist in identifying the underlying mechanisms behind the observed variability.

Known as the "constant bubbling," these punctuations in the disk’s brightness appear to radiate like random bursts of light or heat, but their repeated occurrences and erratic timings hint at an active process within the accretion disk itself. Yusef-Zadeh and colleagues suggest that structure within the disk itself, such as turbulent movements, could be responsible for the changes in brightness. Furthermore, they observe that the same phenomenon that causes the chromatin in a galaxy to lose its structure—magnetic reconnection events—could also contribute to the disk’s flickering. These two processes seem to be in concert, producing the variability observed in the disk.

The discovery of Sgr A‘s activity is a significant leap in our understanding of a system that, despite itsecticity, exhibits behavior that is most often associated with more familiar cosmic phenomena. Analogous to the era-long flares observed on the sun, the bright, often erratic flashes observed from near the galactic center may serve as a testbed for broader hypotheses within astrophysics. As described by Yusef-Zadeh in a review, the research expands our capacity to model such extreme settings and to address questions about how these intense objects interact with the surrounding matter in their vicinity. This understanding may not only encapsulate the peculiar nature of Sgr A but also lay the groundwork for more seismic-like observations on smaller scales, ultimately offering valuable insights into the physics that govern such enigmatic phenomena in the universe.