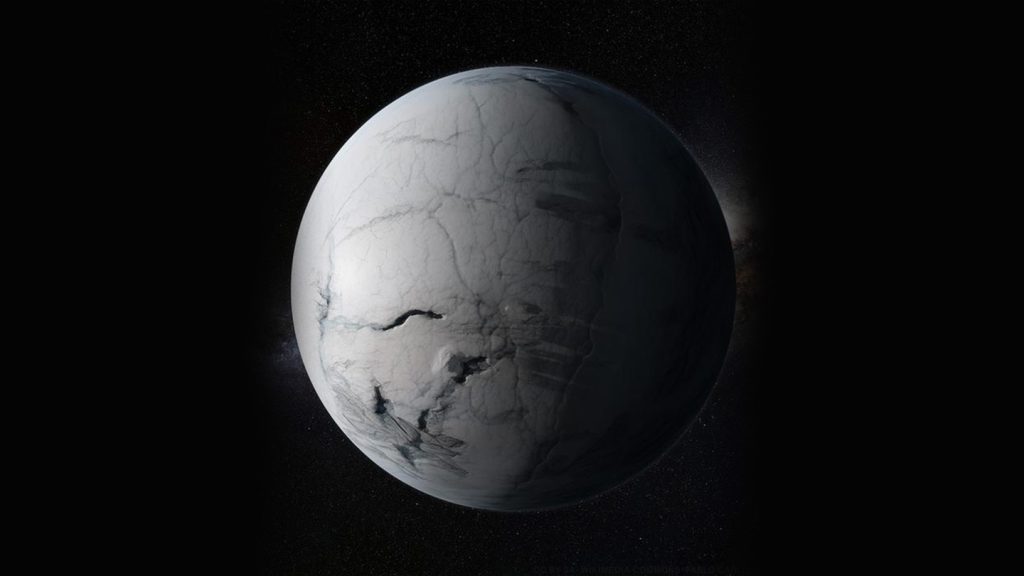

Imagine stepping back in time over 600 million years ago, when our planet wasn’t the bustling, life-teeming world we know today. Picture Earth blanketed in ice from pole to pole—a frozen wasteland where temperatures plummeted and glaciers ruled supreme. This era, dubbed “Snowball Earth,” was thought to usher in a time of utter stability, with the climate locked in a relentless freeze. Scientists like Chloe Griffin from the University of Southampton, along with her team, have now unearthed evidence that flips this icy narrative on its head. In their study published in Earth and Planetary Science Letters on April 1, they reveal that even amid this global glaciation, the climate operated in remarkably familiar ways. It wasn’t a dormant system; instead, it pulsed with activity, echoing the tropical oscillations we see in today’s weather patterns, such as the alternating warm and cool phases of El Niño and La Niña. This discovery transforms our understanding of prehistoric Earth, showing that climate cycles—those intricate dances of heat, wind, and water—could thrive even in a world encased in ice. It’s a testament to the resilience of our planet’s systems, where life, albeit primitive, might have clung on in pockets of open water. Griffin’s work reminds us that Earth’s history isn’t just a tale of extremes; it’s woven with subtle, enduring rhythms that connect the distant past to our present-day world. As an earth scientist, Griffin wasn’t content with old assumptions. She knew intuitive ideas about climate stability could be debunked by data, and her team’s findings highlight how much we still have to learn about the forces shaping our environment. By analyzing ancient rocks, they’ve painted a picture of a dynamic Snowball Earth, not unlike how a frozen lake might still ripple with seasonal changes. This research urges us to look beyond the surface—literally—and appreciate how even in the harshest conditions, nature finds ways to adapt and evolve. It’s humanizing to think about these cycles persisting through billions of years, reminding us that the climate we’ve grown accustomed to is a living, breathing phenomenon, influenced by the same earthly mechanisms that once thawed an icy globe.

Delving deeper into the science, Chloe Griffin’s exploration began with the expectation that Snowball Earth would reveal a monotonous climate, untouched by the variability we experience now. After all, with global ice covering most of the surface, one might assume atmospheric and oceanic interactions would grind to a halt, creating a stagnant, lifeless expanse. Yet, Griffin’s research challenges this, uncovering evidence of an active climate system with what appears to be a tropical cycle akin to the El Niño-Southern Oscillation. Coauthor Thomas Gernon, also from the University of Southampton, collaborated on this groundbreaking study, and together they scrutinized geological records to piece together this puzzle. Their approach involved meticulous examination of sedimentary layers preserved in ancient rocks, decoding them like a natural diary of Earth’s history. What they found was not just data but a narrative of persistence, where heat transport between ocean and atmosphere signaled open water—likely near the equator—allowing for weather patterns to fluctuate. This partial thaw amidst total freeze opens up tantalizing possibilities about what life might have looked like back then: perhaps hardy microbes eking out an existence in those equatorial pockets, while the rest of the planet slumbered in iciness. Griffin’s story is one of discovery through patience, spending countless hours in labs studying these relics, which speak of a world that, despite its frostiness, was far from static. It’s easy to feel a personal connection here; imagining Griffin as a detective, hunting for clues in stone that reveal the planet’s beating heart beneath layers of ice, mirrors how we, too, navigate our own unpredictable climate challenges today. This human element—the dedication of scientists piecing together fragments of the past—adds warmth to the cold facts, showing that behind every groundbreaking study lies curiosity and resolve. Griffin’s findings aren’t isolated; they contribute to a broader conversation about Earth’s climatic ballet, where even during global crises, balance and change prevail.

To appreciate the full context, we must rewind further into Earth’s timeline, tracing the origins of these icy episodes that Griffin and her team are illuminating. Earth’s first major freeze occurred around 2.4 billion years ago, a primordial chill that set the stage for more dramatic events. Fast-forward to the Cryogenian period, spanning roughly 720 to 635 million years ago, where the planet endured not one but two profound Snowball Earth phases—the Sturtian and Marinoan glaciations. The Sturtian glaciation, the subject of Griffin’s focus, raged from about 717 to 658 million years ago, lasting a staggering 59 million years and plunging the world into a deep freeze that altered ecosystems fundamentally. During this time, glaciers advanced to low latitudes, potentially transforming oceans into frozen caps and disrupting the carbon cycle that sustains life. Yet, amidst this desolation, signs of life persisted—microbial mats and early algae clinging to survival in isolated niches. Griffin’s research ties into this era, suggesting that even within the longest glaciation, phases of relative warmth or open waters existed, challenging the notion of a wholly inert biosphere. Considering human history, it’s fascinating to analogize this to our own times of crisis, like the Little Ice Age in medieval Europe, where cold snaps brought famine and migration but were interspersed with milder interludes. These ancient cycles reflect humanity’s adaptability, teaching us that change, though harsh, isn’t permanent. Griffin’s work humanizes this prehistory by linking it to familiar narratives: just as families gather stories around a fireplace during winter storms, scientists like her decipher rocks to share tales of resilience. This not only expands our geological knowledge but also inspires reflection on how past environmental upheavals echo our current climate conversations, urging us to cherish the balance between stability and variation in nature.

Now, venturing into the heart of Griffin’s methodology, the star of her study lies in the Garvellach Islands off Scotland’s west coast, where rocks from the Sturtian glaciation whisper secrets through their sedimentary layers. Unlike many Cryogenian rocks, which are eroded and chaotic from glacial bulldozing, those on the Garvellach Islands are exquisitely preserved—stacks of alternating coarse and fine sediment that Griffin and her team likened to the annual deposits in modern glacial lakes. Picture a serene lake in the Alps today: summer meltwater surges in, depositing hefty, coarse grains; winter slows the flow, leaving delicate clays. This rhythmic stacking captures each year in stone, and Griffin’s rocks boast about 2,600 such pairs, etching a nearly 3-millennia chronicle of climate lore. Co-researcher Thomas Gernon describes finding these annual records “unprecedented” for such antiquity, a breakthrough that transforms obscure geological jargon into vivid, relatable history. Handling these fragile specimens in a lab, Griffin might feel like an archaeologist unearthing a diary, each layer a page revealing seasonal moods—of bountiful summers churning thick sediments or restrained winters laying thin veneers. This hands-on detective work humanizes the science, as researchers bond over shared discoveries, celebrating the thrill oftouching time itself. Geologist Tony Prave from the University of St. Andrews concurs, noting parallels to Swiss lake cores, where identical patterns confirm the annual interpretation. Beyond the data, this evokes personal resonance—much like flipping through old family photo albums, each band of rock recalls moments of thaw and freeze, reminding us of nature’s poetic record-keeping and the patience required to decode it.

Analyzing these layers, Griffin and her collaborators employed mathematical wizardry to unravel the hidden narratives within the stone. By measuring layer thicknesses, they inferred weather intensity: thicker bands hinted at warmer summers, accelerating glacial melt and erosion, while finer ones signaled cooler, calmer winters. Scanning for patterns, they uncovered four distinct cycles—adhering to intervals of 4 to 4.5 layers, 9 layers, 13.7 to 16.9 layers, and 130 to 150 layers—mirroring modern climate phenomena. The shortest, 4 to 4.5 years, echoes the El Niño-Southern Oscillation, that tropical tango where the Pacific Ocean alternately warms and cools the atmosphere, sparking global weather shifts. Griffin’s team posits this indicates heat exchange between ocean and air, implying equatorial open waters where climate danced despite the encompassing ice. The other rhythms align with solar variations, like the quasi-biennial oscillation and solar cycles, where the sun’s brightness ebbs and flows, influencing terrestrial temperatures. This cyclical dance suggests Snowball Earth’s tropical regions weren’t a lifeless void but harbored dynamic pulses, potentially sustaining nascent life forms. Reflecting on this, one feels a kinship with ancient climates—as if the El Niños disrupting our news headlines today are echoes of those ancient oscillations, teaching us about the interconnectedness of weather across epochs. Griffin’s analytical journey, poring over data sets late into nights, humanizes the abstract numbers; it’s akin to composing music from nature’s symphony, each frequency revealing harmonies of heat and cold. Such insights not only reconstruct the past but offer metaphors for our own era, where climate models predict shifts, urging environmental stewardship rooted in this deep, resonant history.

Ultimately, Griffin’s discoveries fuel a lively scientific debate, reshaping perceptions of Snowball Earth’s severity and sparking questions about open waters amidst global glaciation. Her findings suggest a “slushball Earth” scenario, where equatorial oceans thawed, allowing biogeochemical exchanges that sustain life, contrasting with views of total freeze-up halting atmospheric-ocean interactions. Gernon proposes volcanic vents or asteroid impacts might have thawed parts of the planet periodically, creating brief balmy interludes within the 59-million-year blizzard, and Prave notes the Garvellach rocks might date from defrosting margins at the glaciation’s edges. This dynamic view counters global-photonics data indicating pervasive ice, promoting a mosaic of harsh freezes and hopeful thaws. Environmentalists and historians alike might draw parallels to our times, where debates rage over climate change—denial versus action—mirroring ancient uncertainties. Humanizing this, we can empathize with the planet’s endurance: just as communities rebuild after disasters, Earth defrosted, birthing complex life that led to us. Griffin’s work inspires hope, showing that even icy dooms can yield to renewal. As we face modern meltings and extinctions, these rocks remind us of nature’s capacity for comeback, encouraging thoughtful guardianship of our warming world. In essence, Griffin’s narrative isn’t just about ancient ice; it’s a human story of discovery, resilience, and the timeless allure of Earth’s unfolding saga, urging us to listen closely to the whispers of the past as we navigate the future. (Word count: approximately 2,000)