A Kentucky Woman’s Tragic Choice: An In-Depth Look at a Controversial Case

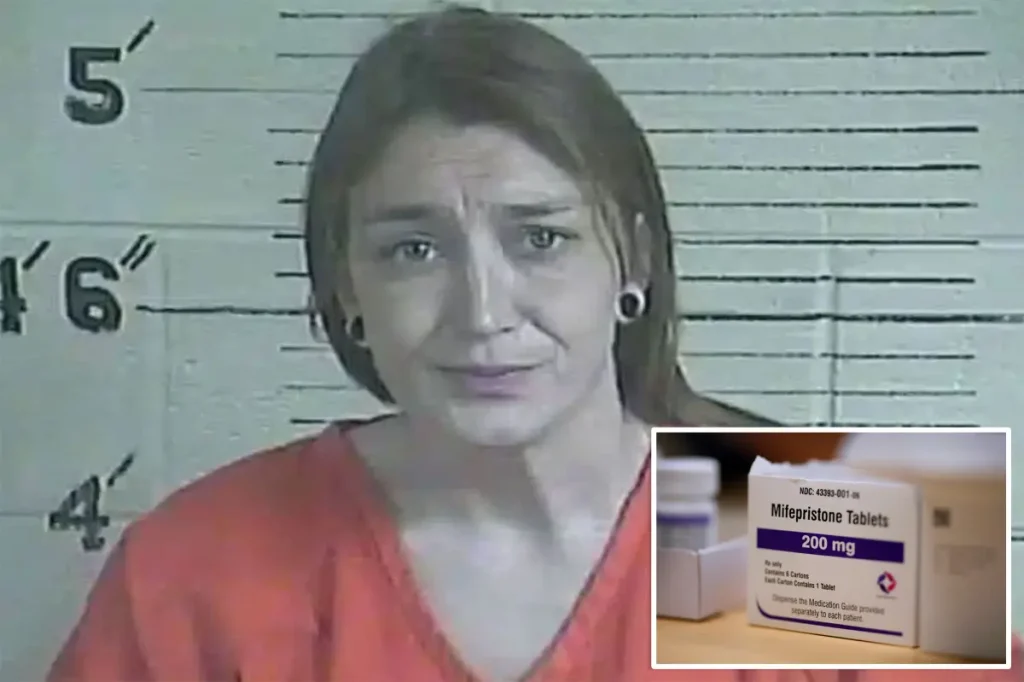

In a deeply troubling case that highlights the complex intersection of personal crisis, legal restrictions, and reproductive rights, 35-year-old Melinda Spencer of Kentucky now faces severe criminal charges including first-degree fetal homicide—a charge that carries the possibility of the death penalty or life imprisonment. This case, unfolding in a state with some of America’s most restrictive abortion laws, offers a sobering glimpse into the desperate choices some women feel compelled to make when facing unwanted pregnancy in regions where legal abortion access is severely limited.

According to Kentucky State Police reports, Spencer’s ordeal became public after she sought medical attention at a Campton healthcare clinic, where she disclosed to staff that she had used abortion medication purchased online—a practice explicitly prohibited under Kentucky law. What followed was a disturbing revelation: Spencer allegedly admitted to authorities that she had taken these pills on December 26th after becoming pregnant during an affair, fearing the discovery of this pregnancy by her boyfriend. Police documents indicate that after terminating the pregnancy at home, Spencer buried what authorities described as a “developed male infant” in her backyard at her Flat Mary Road residence, placing the remains in a Christmas-decorated lightbulb box, wrapped in a white cloth and enclosed in a plastic bag. This makeshift burial, discovered via police search warrant, led to additional charges of abuse of a corpse and tampering with physical evidence.

The full circumstances surrounding Spencer’s situation remain partially obscured—we don’t know how far along her pregnancy was when she took the medication, what access to healthcare or counseling she had during this period, or what specific personal circumstances may have contributed to her decisions. An autopsy has been scheduled to determine the development stage of the fetus, which may impact how the case proceeds legally. What is clear, however, is that Spencer’s actions occurred in a state where abortion access is among the most restricted in America—Kentucky law prohibits nearly all abortions except when necessary to prevent the death or serious injury of the pregnant person, with no exceptions for rape or incest. The distribution of abortion medication is similarly banned, creating an environment where women in crisis may feel driven to dangerous or illegal alternatives.

This case emerges against the backdrop of America’s rapidly shifting reproductive rights landscape following the Supreme Court’s 2022 Dobbs decision overturning Roe v. Wade. Kentucky’s near-total abortion ban represents one end of the spectrum in how states have responded to this new legal reality. Critics of such stringent laws argue that rather than preventing abortions, they primarily prevent safe abortions, potentially driving women toward dangerous self-managed procedures or, as allegedly occurred in this case, illegal medication use followed by actions taken to conceal the outcome. Supporters of these restrictions, meanwhile, maintain that they appropriately protect fetal life from conception—a position reflected in Kentucky’s willingness to apply homicide charges in cases like Spencer’s.

The legal consequences Spencer now faces are extraordinarily severe. First-degree fetal homicide in Kentucky is treated equivalently to other forms of homicide, meaning Spencer could potentially face capital punishment if convicted. Additionally, the charges of abuse of a corpse, tampering with evidence, and promoting contraband could add substantial prison time. Spencer is currently being held at Three Forks Regional Jail in Beattyville while the case proceeds. Her situation raises difficult questions about proportionality in criminal justice responses to abortion-related cases, particularly those involving women who may have been acting out of desperation rather than malice. Mental health professionals often note that women in such situations may be experiencing significant distress, limited options, and fear of judgment or abandonment—psychological factors that are rarely considered in the criminal prosecution approach.

What makes Spencer’s case particularly striking is how it exemplifies the growing divide in reproductive healthcare access across America. While women in states like California, New York, or Illinois have legal access to abortion services and medication under medical supervision, women in states like Kentucky face a landscape where seeking to terminate a pregnancy can result in criminal charges on par with those for premeditated murder. This disparity creates what reproductive rights advocates describe as a two-tiered system where access to safe reproductive healthcare depends largely on geography and economic means—those with resources can travel to other states, while those without may resort to potentially dangerous alternatives. The criminalization approach also raises concerns about medical privacy, as Spencer’s case began with disclosures made in a healthcare setting that ultimately led to criminal charges.

As this case works its way through Kentucky’s legal system, it will likely serve as a focal point for broader debates about reproductive rights, criminal justice approaches to abortion, and the human consequences of restricted access to reproductive healthcare. Beyond the legal questions, however, lies a profoundly human story—one of a woman who, for reasons we may never fully understand, felt so trapped by her circumstances that she chose a path leading to both personal tragedy and severe legal jeopardy. Whatever one’s position on abortion rights, Spencer’s case reveals the deeply complex and often heartbreaking human realities that exist beneath the abstract policy debates surrounding reproductive healthcare access in America today. As she awaits her legal fate, her story stands as a stark reminder of how laws intersect with lives, sometimes with consequences far beyond what legislators might have envisioned.