The Pressman Family Feud: Barneys, Books, and Legal Battles

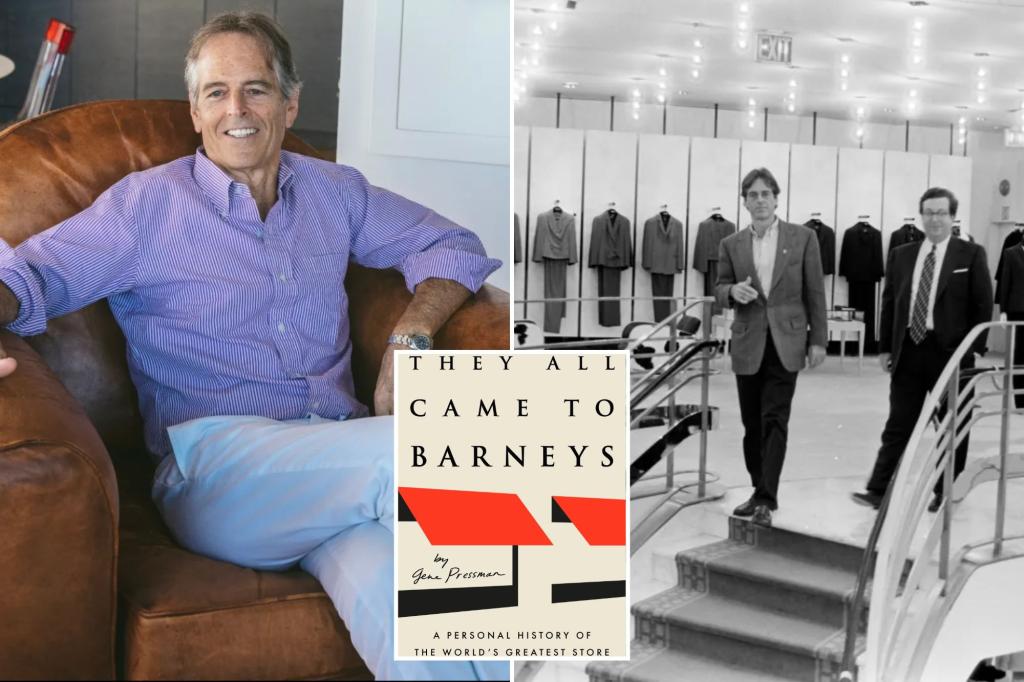

In a dramatic scene straight out of a New York society novel, 74-year-old Gene Pressman’s book signing for his memoir “They All Came to Barneys: A Personal History of the World’s Greatest Store” took an unexpected turn last Tuesday at Manhattan’s Rizzoli Bookstore. As Gene sat signing copies for fashion enthusiasts, a process server posing as a fan approached the table. Instead of presenting a book to be signed, the server handed Gene a lawsuit filed by his estranged younger brother, Bob Pressman. According to witnesses, Gene’s reaction was explosive—he reportedly erupted in a stream of curses, clearly blindsided by this public confrontation. The lawsuit is no minor family squabble but rather an explosive accusation of tax fraud that could amount to $50 million in back taxes and penalties. This public ambush at what should have been a celebratory literary event perfectly encapsulates the bitter divide that has fractured the once-powerful fashion family behind the legendary Barneys New York luxury empire.

The lawsuit, recently unsealed by a judge in June, reveals the depth of the family discord. Bob Pressman, 71, has accused his brother Gene, his two sisters Elizabeth Pressman-Neubardt and Nancy Pressman-Dressler, and their late mother Phyllis of orchestrating an elaborate tax fraud scheme that allegedly cheated New York State out of $20 million. At the heart of the allegations is the claim that the family falsely stated their mother resided in tax-friendly Florida when she had actually been living year-round in her oceanfront Southampton mansion for the last six years of her life. Bob filed the complaint as a whistleblower under the New York False Claims Act, which could entitle him to as much as 30% of any recovery—a significant financial incentive in addition to whatever personal satisfaction he might derive from exposing his family. According to Randall Fox, Bob’s attorney, Gene’s sisters have already been served with the lawsuit in the New York metro area, while Gene, who now lives in West Palm Beach, Florida, had been more elusive until his book tour brought him back to Manhattan.

The family’s fractured relationships stem from their complicated history at Barneys New York, the luxury department store their grandfather Barney Pressman founded in 1923. Fred Pressman, their father, transformed the business from a discount men’s suit shop into a luxury fashion destination in the 1960s. The siblings worked together at the company during its ambitious expansion in the 1980s and 1990s, which unfortunately led to a bankruptcy filing in 1996. Gene and Bob served as co-CEOs during this tumultuous period, with Gene handling the creative direction while Bob managed the finances. Their working relationship disintegrated after the family sold their stake in Barneys more than 25 years ago, and the siblings have since engaged in a bitter war of words and legal actions. The current lawsuit represents just the latest—and perhaps most explosive—chapter in their ongoing feud, with Bob claiming he was cut out of his mother’s estimated $100 million estate after refusing to participate in the alleged tax scheme.

The assets at stake in this family drama are substantial. Phyllis Pressman, who passed away last year at age 95, left behind a 2.3-acre oceanfront property in Southampton currently listed for $38.5 million, as well as an Upper East Side apartment in Manhattan that’s in contract for $3.95 million. According to the lawsuit, Phyllis left nothing to Bob from her substantial estate. A trust agreement prepared by her attorneys bluntly stated that “Bob doesn’t get anything for reasons he well knows,” suggesting a deep-seated family rift that extended to the matriarch’s final wishes. This exclusion seems to have motivated Bob’s decision to pursue legal action against his siblings, though he has declined to comment directly on the lawsuit. The family’s wealth derived from Barneys’ success makes the stakes of this legal battle particularly high, with potentially tens of millions of dollars in play.

The Pressman siblings’ troubled relationship has played out in multiple legal arenas over the years. After the 1996 Barneys bankruptcy, sisters Elizabeth and Nancy sued Bob, accusing him of cheating them out of $30 million from the business. A New York judge awarded them $11.3 million in 2002, though Bob appealed the decision. More recently, Bob had been working on an unpublished manuscript for a tell-all book that blamed his family for Barneys’ downfall, particularly accusing Gene of running the company into the ground with excessive spending while allegedly partying at Studio 54 throughout the 1980s. Gene countered these accusations by pointing out that Bob was the co-CEO responsible for financial stability, “a role in which by all measures he massively failed.” These mutual recriminations reveal deeply entrenched positions and resentments that have festered for decades, making reconciliation seem increasingly unlikely.

The public serving of legal papers at Gene’s book signing represents more than just a practical method of delivering a lawsuit—it symbolizes how personal this battle has become. The timing seems calculated to maximize embarrassment during what should have been a proud moment for Gene as he celebrated his literary achievement chronicling the glory days of Barneys. The luxury retailer, which filed for bankruptcy again in 2019 and closed its doors after nearly a century in business, now exists primarily in the memories of fashion enthusiasts and in the pages of Gene’s memoir. Meanwhile, the Pressman family legacy has become entangled in bitter accusations, counter-claims, and now potential tax fraud—a far cry from the glamorous image the store once projected. As Gene now has 20 days to respond to the lawsuit, this family drama continues to unfold, revealing how even the most successful business dynasties can crumble not just financially, but personally. The Pressman saga serves as a cautionary tale about family business, wealth, and the devastating impact of broken relationships that no amount of luxury goods can repair.