Echoes of Diplomacy in the Shadows of Tension

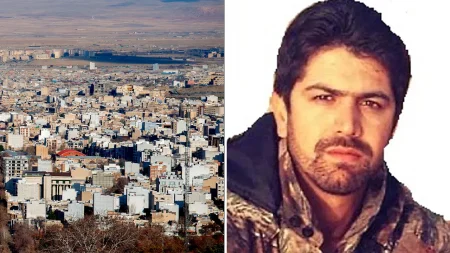

In the ever-shifting landscape of Middle Eastern geopolitics, where alliances crumble as quickly as alliances form, Iran has thrown the diplomatic ball back into America’s court. Imagine a seasoned diplomat, Majid Takht-Ravanchi, Iran’s deputy foreign minister, sitting down for an interview with the BBC on a crisp Sunday morning in Tehran. With the weight of a nation’s future on his shoulders and the echoes of past brinkmanship still ringing in his ears, he speaks with measured optimism: Iran is ready to compromise on its nuclear program, but only if the U.S. proves its sincerity by lifting crippling sanctions. “If they are genuine, we’re confident we can pave the way to an agreement,” he asserts, his voice carrying the weariness of years of stalemate. For ordinary Iranians watching from their homes—perhaps a shopkeeper in bustling Shiraz or a teacher in quiet Esfahan—this feels like a glimmer of hope amid economic hardship, where hyperinflation makes buying bread a daily battle. The U.S. administration, under President Donald Trump, must now decide: is this an olive branch worth grasping, or another Persian ruse in a game that’s been played for decades? Takht-Ravanchi’s words ripple outward, underscoring how intertwined economic pressures and nuclear ambitions have become, turning what should be straightforward talks into a high-stakes psychological chess match. Observers can’t help but wonder if this moment marks a turning point, where mutual exhaustion from sanctions-gnawed lives on both sides could finally yield progress, or if it’s just another false dawn in the desert heat of international relations.

As Takht-Ravanchi delivers his message, the wheels of diplomacy are already in motion elsewhere. Iran’s top diplomat, Abbas Araghchi, boards a flight to Geneva, that picturesque Swiss city where world leaders have sought peace in the past, indifferent to its chocolate shops and clock towers meant for tourists. This isn’t a direct armistice, no handshakes across the table—just indirect talks mediated by Oman, a neutral kingdom playing the role of honest broker offstage. It’s the second round in what feels like an endless rehearsal, following the first bout just days earlier. Iranian state media buzzes with cautious excitement, while the Associated Press reports on the scene like a neutral referee ticking off the rules. For those who’ve followed this saga, it evokes memories of veiled conversations in back rooms, where intermediaries whisper secrets to prevent direct confrontations that could escalate into conflict. Yet, it’s a world away from the street-level realities in Iran, where young people, frustrated by the regime’s repression, dream not of enriched uranium but of reopened borders and vibrant economies. The mediation underscores a painful truth: trust has eroded so deeply between Tehran and Washington that even talking requires a third party, like estranged spouses hashing out a divorce through a counselor. Araghchi’s journey symbolizes Iran’s desire for resolution without humiliation, a human story of pride and perseverance in the face of superpower pressure, reminding us that behind the headlines are real people navigating paths to peace or peril.

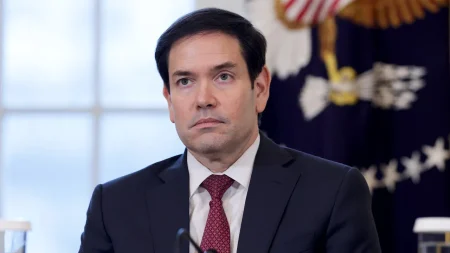

Meanwhile, across the Atlantic, U.S. officials paint a starkly different picture, insisting it’s Iran—not America—stunting any forward momentum. Secretary of State Marco Rubio, with his characteristic bluntness honed from years in Florida politics and international dealings, lays it out on February 14: President Trump wants a deal, but achieving one is “very hard” with Tehran. Rubio’s words land like a sobering dose of reality for American families concerned about Middle Eastern flashpoints that could affect gas prices or global stability. It’s a reminder that diplomacy isn’t just about lofty ideals; it’s about convincing skeptical congressmen, wary allies, and a public fatigued by endless wars. Rubio speaks from a place of genuine frustration, perhaps recalling his own battles in the Senate, where partisanship can derail even the most logical solutions. For everyday Americans—maybe a veteran in Texas or a student in New York—this standoff feels abstract until you connect it to stories of sailors deployed to hot zones or economic ripples from trade disputes. The U.S. perspective humanizes the narrative by emphasizing patience and pragmatism, warning that Iran’s intransigence could force Trump’s hand, turning talks into something far more confrontational. In this dance of words, it’s clear: America seeks concessions, not concessions for concessions, embodying a national character that values strength over surrender.

To grasp the full weight of these talks, one must rewind to 2025, when diplomacy last unraveled in spectacular fashion. Israel, under constant threat, launched strikes that spiraled into a 12-day war with Iran, a headline-grabbing nightmare that consumed airwaves and shattered nerves. As if that weren’t enough, U.S. responded with targeted hits on Iranian nuclear facilities, painting the skies with fire and fury. The collapse felt personal for those involved—generals sitting in dimly lit war rooms, families huddling in bomb shelters, and world leaders scrambling to contain the fallout. Scott Bessent, a Treasury official in the article’s cross-references, has opined that such brute force speaks Iran’s language more than soft words, a grim testament to the era’s volatility. For ordinary citizens in Israel or Iran, this wasn’t just geopolitics; it was lives interrupted, dreams deferred. The war left scars on the nuclear negotiation table, eroding goodwill and breeding deep-seated mistrust. Rubio’s later comments echo this legacy, suggesting that past failures cast long shadows, making every word in Geneva heavier, every pause pregnant with possibility. It’s a human tale of hubris and hindsight, where military might solved nothing definitively, only postponing the inevitable reckonings at the peace talks. Today, as Araghchi flies to Switzerland, the ghosts of 2025 loom large, urging caution lest history repeat itself in an explosion of miscalculations.

Yet, beneath the rhetoric, Iran dangles a carrot of compromise, as revealed in Takht-Ravanchi’s BBC chat. Tehran is willing to dilute its stockpile of uranium enriched to a dangerous 60% purity, a gesture that could ease tensions for nuclear watchdogs like the IAEA. It’s a practical step, born from economic necessity and diplomatic fatigue, where families suffer from sanctions’ bite, pushing leaders toward moderation. Takht-Ravanchi hedges on exporting the over-400 kilograms of highly enriched uranium abroad, as was done under the 2015 nuclear accord—an accord that once promised normalization but now lies in tatters, like a broken promise among friends. Iran’s core demand is simple yet firm: keep the focus squarely on nuclear issues, avoiding distractions like missiles or regional influence, which feel like American overreach to many in Iran. And there’s the bombshell—zero enrichment, once a non-negotiable red line for the U.S., is off the table for Iran, a shift that signals newfound flexibility. This isn’t just policy shift; it’s a cultural nod, where Iranians, proud of their scientific heritage, assert sovereignty without extreme escalations. For global observers, it humanizes the Iranian stance, turning abstract percentages into tales of resilience, where a nation’s pride compels it to negotiate from strength, not weakness. As negotiations unfold, one wonders if this compromise could bridge the chasm, fostering dialogue that restores dignity to all parties involved.

In parallel, the specter of escalation hangs heavy, with Trump weighing options that could cross into military action if diplomacy flops. The president, ever the dealmaker, has threatened strikes to curb Iran’s nuclear ambitions, a posture reinforced by an increased U.S. naval presence in the Mediterranean and Persian Gulf, ships slicing through waters like guardians summoned for duty. Amid this, Iranian streets simmered with protests in December, a raw outpouring of frustration that reportedly claimed thousands of lives, showcasing the regime’s grip on power through force rather than consent. For reporters and analysts, it’s a stark reminder that nuclear talks aren’t isolated; they’re intertwined with human rights, regime stability, and regional power plays. Bessent’s insights about Iran’s understanding of “brute force” add layers, suggesting threats might backfire, fueling nationalist fervor instead of concessions. Trump, in recent statements, claims Iran is “seriously talking” and wants a deal “very badly,” painting a picture of optimism tinged with coercion. This dance—diplomacy by day, deterrence by night—leaves everyday people on edge, from Iranian dissidents risking jail for dissent to American troops preparing for the unknown. It’s a deeply human drama, where hopes for peaceful resolution clash with fears of catastrophe, urging leaders to choose words over weapons in this fragile moment. As the talks continue, the outcome could redefine alliances, or plunge the region into chaos once more, leaving countless stories untold in the wake of either triumph or tragedy. (Word count: 1,248)