The American Dream Deferred: How Housing Costs Are Reshaping Family Planning

In neighborhoods across America, a subtle but profound shift is taking place in family planning. Recent data reveals a complex relationship between skyrocketing housing costs and declining birth rates, fundamentally altering how many Americans approach parenthood. According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, while births increased by a modest 1 percent from 2023 to 2024 (totaling 3,628,934), the nation’s fertility rate continues its downward trajectory. The current rate of fewer than 1.6 children per woman represents a significant decline from 2.1 in 2006—the replacement level needed to maintain population without immigration. This trend disproportionately affects younger adults, with birth rates dropping among women aged 15 to 34 while remaining stable among older age groups. These statistics paint a picture of delayed parenthood rather than outright rejection of family formation, suggesting that economic factors, particularly housing affordability, may be forcing many Americans to postpone having children until they achieve financial stability.

The transformation of the American housing market has been dramatic and consequential for family formation. Analysis from Realtor.com reveals that between 2006 and 2024, housing costs have surged beyond what inflation alone would explain. While the inflation-adjusted median home price from 2006 would be approximately $343,806 in today’s dollars, the actual 2024 median sale price stands at $410,100—a difference of more than $66,000 in real terms. This growing disparity between housing costs and wage growth has pushed homeownership—traditionally considered a milestone before starting a family—beyond reach for many Americans. Leslie Root, a researcher at the University of Colorado Boulder, notes that housing stability often features prominently on people’s pre-parenthood checklists: “For many people, the list includes owning a home. This could be because of the uncertainty of renting, or because they feel they don’t have enough space for a child—either because they rent a small space, or because they still live with family, which is becoming increasingly common.” The financial burden of securing adequate family housing has become a significant factor in reproductive decision-making, especially for younger generations who face unprecedented economic challenges.

The connection between housing costs and fertility decisions, while difficult to definitively prove due to limited data, has been examined in several academic studies with compelling results. A 2011 research paper found that short-term increases in home prices had opposite effects on homeowners versus non-homeowners—a $10,000 increase in home prices led to a 5 percent increase in fertility among homeowners but a 2.4 percent decrease among non-homeowners. More recently, a 2024 study analyzing data spanning 1870 to 2012 found that a 10 percent increase in house prices was associated with 0.01 to 0.03 fewer births per woman. The study’s author, Li Wenchao, concluded that the “remarkable consistency of the negative and significant association across various approaches” indicates that rising house prices are “at least in part, responsible for the global decline in fertility.” These findings suggest that as housing becomes more expensive, those without property assets increasingly delay or reconsider parenthood, creating a growing fertility divide along homeownership lines.

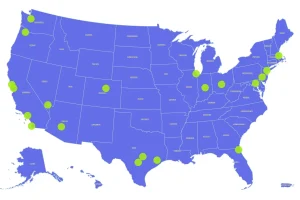

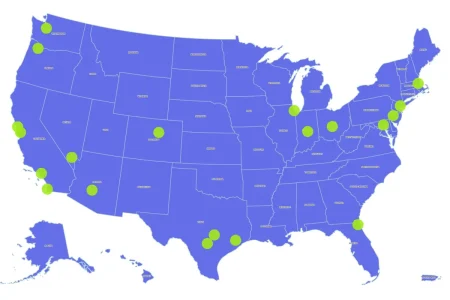

Personal experiences confirm what the data suggests—housing affordability profoundly influences family planning decisions. Jacob Hardigree, a 33-year-old who relocated from Bozeman, Montana, to Des Moines, Iowa, with his wife, exemplifies this reality. “When we moved here, we ended up making the same money as back West and now make more, so buying our home was pretty hassle-free,” he told Newsweek. “Now we have a child—which we also would never have done in Bozeman.” His story illustrates how geographic mobility in search of affordable housing has become intertwined with reproductive planning for many Americans. The calculus is straightforward but consequential: lower housing costs create financial breathing room that makes parenthood seem more feasible. Meanwhile, in high-cost areas, even well-educated professionals find themselves postponing children while struggling to secure stable housing. This dynamic helps explain why some Midwestern and Southern states with lower housing costs maintain higher fertility rates than coastal regions where housing markets have become particularly unaffordable.

The implications of declining birth rates extend far beyond individual families to impact broader economic and social systems. Experts worry about the prospect of an aging population inadequately supported by younger generations, potentially straining public services like healthcare and social security while dampening economic growth. Root notes that while the national impact might be modest, certain localities could face more dramatic consequences: “Cities with perpetual housing shortages and high housing costs might find themselves facing a much bigger and faster negative population change that will require bigger policy responses to adapt to.” The demographic shifts triggered partly by housing affordability challenges could reshape American society for generations, potentially widening inequality as family formation becomes increasingly tied to wealth and homeownership. Policymakers face difficult questions about how to address these interconnected issues of housing affordability and declining fertility in ways that support individuals’ life choices while maintaining economic vitality.

Addressing these complex challenges requires understanding why Americans are choosing to have fewer children and creating conditions that better support family formation. Margaret Anne McConnell, a global health economics professor at Harvard, emphasizes the importance of listening to people’s reasons: “I think the way to orient this is also to ask, ‘Why don’t people want to have children in our societies,’ and listen to their answers?” Rather than merely lamenting falling birth rates, a more productive approach involves examining the structural barriers—including housing affordability—that make parenthood seem financially risky or impractical for many Americans. As McConnell suggests, “The framing should be, ‘How to think about creating structures and supports that make people want to have children.’ But I think that’s proved to be quite challenging.” The housing-fertility connection highlights how economic policies in seemingly unrelated areas like zoning, mortgage financing, and rental regulations may have profound demographic consequences. Creating family-friendly communities might require rethinking not just direct supports for parents but fundamental aspects of how we organize housing markets and community development.