Japan’s Nuclear Renaissance: Navigating Energy Needs, Safety Concerns, and Public Opinion

Japan stands at a critical energy crossroads as it prepares to restart the world’s largest nuclear reactor in Niigata Prefecture, signaling a significant shift in the nation’s nuclear policy since the 2011 Fukushima disaster. This milestone represents the 15th reactor to resume operations nationwide and, perhaps more symbolically, the first restart for Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO) since its Fukushima Daiichi plant experienced a catastrophic meltdown following the devastating tsunami that struck Japan’s eastern coast. The Kashiwazaki-Kariwa plant in Niigata houses seven reactors, with one scheduled to return to operation around January 20th after securing local government approval. This development emerges within a complex landscape of energy security concerns, where Japan—a resource-poor nation—has struggled with soaring electricity costs due to heavy reliance on imported fossil fuels. Public sentiment toward nuclear power has gradually warmed, with recent polling suggesting nearly 45 percent of Japanese citizens now support reviving nuclear energy, while 26 percent remain opposed. This evolving perspective reflects both pragmatic economic considerations and confidence in strengthened safety regulations implemented in the aftermath of Fukushima.

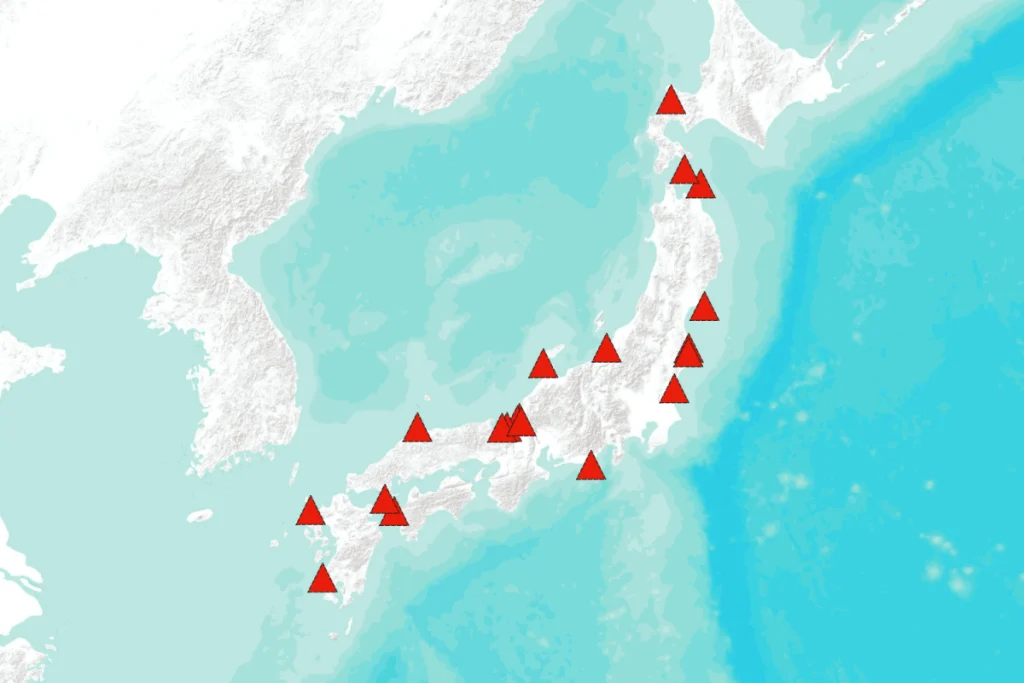

The nuclear restart represents just one component of Japan’s broader energy strategy, which aims to achieve approximately 20 percent of electricity generation from nuclear sources by 2030—a more modest target compared to the roughly 30 percent share before the 2011 disaster. Currently, 14 reactors operate across eight plants on the islands of Honshu, Shikoku, and Kyushu, with another 10 reactors awaiting approval for restart, including one in Hokkaido. Two additional facilities remain in operational limbo with uncertain futures. This measured return to nuclear power reflects Japan’s delicate balancing act between addressing immediate energy needs and respecting lingering public anxieties about nuclear safety. Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi has emerged as a strong advocate for nuclear power, positioning it as central to achieving greater energy independence. Her administration has also emphasized the development of advanced nuclear technologies, including fusion energy, while placing comparatively less emphasis on renewable energy sources. This policy direction aligns with industrial interests represented by organizations like the Japan Business Federation, whose members recently toured the Kashiwazaki-Kariwa plant, where TEPCO President Tomoaki Kobayakawa declared that “the use of nuclear energy is essential in Japan, which has few resources.”

Despite this pro-nuclear momentum, Japan’s nuclear industry continues to face significant challenges related to safety concerns and public trust. Just as the Niigata restart was being finalized, Japan’s nuclear regulatory authority revealed troubling “wrongdoing” by another utility company, Chubu Electric. According to whistleblower reports, the company allegedly submitted seismic safety data for its Hamaoka plant that differed from internal figures—a particularly alarming revelation given the facility’s precarious location. The Hamaoka plant sits near the Nankai Trough, an underwater seismic zone where experts anticipate a potentially catastrophic “megaquake” within the coming decades. Government estimates suggest such an event could result in nearly 300,000 deaths and approximately $2 trillion in economic damage. This disclosure underscores the immense safety stakes involved in Japan’s nuclear operations and highlights why public skepticism persists despite enhanced regulatory frameworks. Even in Niigata, where the restart received official approval, Governor Hideyo Hanazumi acknowledged to Prime Minister Takaichi that “many residents in the prefecture still feel uneasy about the restart, and many harbor distrust toward the operator.”

The human dimensions of Japan’s nuclear policy extend beyond statistical risk assessments and economic calculations, touching on deep-seated anxieties that continue to resonate more than a decade after Fukushima. For communities hosting nuclear facilities, the benefit-risk equation remains deeply personal and complex. Families living in the shadow of cooling towers weigh tangible economic benefits—jobs, tax revenue, infrastructure investments—against less visible but potentially catastrophic risks amplified by Japan’s seismic vulnerability. The government and utility companies have invested substantially in rebuilding public confidence through enhanced safety systems, transparent communication channels, and community engagement initiatives. Yet the psychological trauma of the 2011 disaster lingers in the national consciousness, creating an atmosphere where even routine maintenance activities at nuclear plants can trigger heightened public concern. This psychological backdrop explains why official approval processes for reactor restarts now incorporate extensive community consultations and local government sign-offs—a recognition that technical safety assessments alone are insufficient to secure public acceptance.

From a global perspective, Japan’s cautious nuclear revival reflects broader international reconsiderations of nuclear energy’s role in addressing climate change while ensuring energy security. As one of the world’s most technologically advanced economies with limited domestic energy resources, Japan’s policy choices carry significant implications for other nations navigating similar challenges. The country’s measured approach—neither abandoning nuclear power entirely nor rushing to restore pre-Fukushima capacity levels—represents a middle path informed by painful experience. This strategy acknowledges both nuclear energy’s capacity to provide stable, low-carbon electricity and the catastrophic consequences of safety failures in seismically active regions. Japanese policymakers have increasingly framed nuclear power as part of a diversified energy portfolio that balances multiple objectives: reducing carbon emissions, containing electricity costs, maintaining industrial competitiveness, and preserving energy independence. Prime Minister Takaichi’s October policy speech to the National Diet emphasized that nuclear initiatives would proceed only with “gaining the understanding of the local communities and on giving due regard to environmental impacts,” signaling the government’s recognition that public acceptance remains as crucial as technical feasibility.

Looking ahead, Japan’s energy transition faces significant uncertainty, with nuclear power representing just one contentious element in a multifaceted challenge. The scheduled restart of TEPCO’s Kashiwazaki-Kariwa reactor marks an important milestone but not a definitive resolution to Japan’s energy dilemma. The government’s target of generating 20 percent of electricity from nuclear sources by 2030 will require continued progress in restarting idled reactors while addressing ongoing safety concerns and rebuilding community trust. Simultaneously, Japan must accelerate development of renewable energy capacity to meet its climate commitments while exploring next-generation nuclear technologies that might offer enhanced safety features. The recent revelation of potential data manipulation at the Hamaoka plant serves as a sobering reminder that the nuclear industry’s path forward depends not only on technical capabilities but on organizational integrity and transparent governance. For ordinary Japanese citizens, these high-level policy decisions translate into deeply practical concerns about electricity bills, environmental health, and community safety. As Japan cautiously embraces its nuclear restart, the nation continues its complex journey toward an energy future that reconciles technological ambition with the hard lessons of Fukushima.