Nobel Laureate David Baker’s Lab Reveals Groundbreaking Advances in AI Protein Design

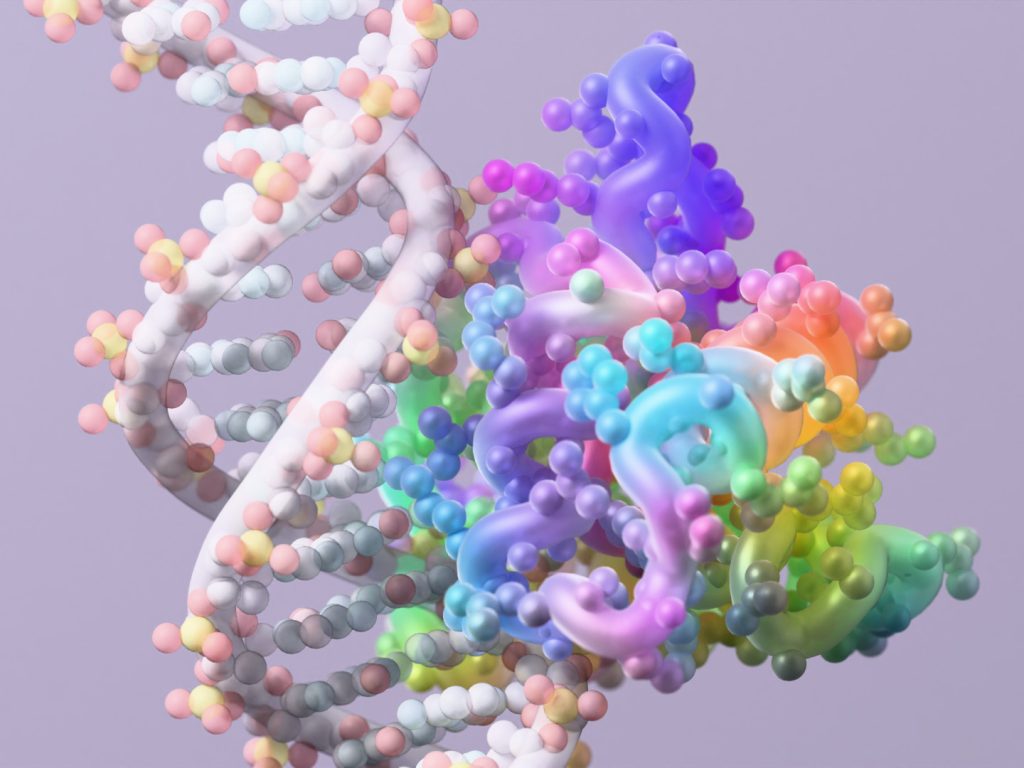

The University of Washington’s Institute for Protein Design, led by Nobel laureate David Baker, has unveiled two major breakthroughs in AI-powered protein engineering that could revolutionize medicine and sustainability efforts. The first advancement is a significantly improved version of their RFdiffusion2 tool, now capable of designing enzymes that perform nearly as well as those created through billions of years of evolution. The second is the release of RFdiffusion3, described as their most powerful and versatile protein engineering technology to date. These innovations, published in prestigious journals Nature and Nature Methods, represent a quantum leap in our ability to create custom proteins for solving complex problems in healthcare and environmental science.

The enhanced RFdiffusion2 employs a more hands-off approach to enzyme design, allowing the AI system greater freedom to explore potential solutions while adhering to the fundamental laws of chemistry and physics. “You basically let the model have all this space to explore and… you really allow it to search a really wide space and come up with great solutions,” explains Seth Woodbury, a graduate student in Baker’s lab and co-author on both papers. This approach has yielded remarkable results, with the tool successfully solving all 41 challenging enzyme design tasks presented to it—a dramatic improvement over the previous version’s success rate of just 16. Perhaps more significantly, these engineered enzymes are approaching the efficiency of naturally occurring ones, which Rohith Krishna, a postdoctoral fellow and lead developer of RFdiffusion2, notes is unprecedented: “This is one of the first times that we’re not one of the best enzymes ever, but we’re in the ballpark of native enzymes.”

One particularly promising application demonstrated by the team involves the creation of metallohydrolases—specialized enzymes that accelerate difficult chemical reactions using precisely positioned metal ions and activated water molecules. These engineered proteins could have far-reaching implications, including the breakdown of environmental pollutants. The potential for rapidly designing catalytic enzymes opens up numerous possibilities, especially in sustainability efforts. “The first problem we really tackled with AI was largely therapeutics, making binders to drug targets,” Baker explains. “But now with catalysis, it really opens up sustainability.” Additionally, the researchers are collaborating with the Gates Foundation to develop more cost-effective methods for producing small molecule drugs, which work by interacting with proteins and enzymes inside cells to influence biological processes.

While RFdiffusion2 excels at enzyme creation, the research team recognized the need for a more versatile tool capable of addressing a broader range of protein design challenges. This led to the development of RFdiffusion3, a general-purpose AI model that can create proteins to interact with virtually any type of molecule found in cells, including DNA, other proteins, and small molecules, in addition to performing enzyme-related functions. “We really are excited about building more and more complex systems, so we didn’t want to have bespoke models for each application. We wanted to be able to combine everything into one foundational model,” Krishna, who also led the development of this new model, explains. In a significant move toward scientific collaboration, the team has made the code for RFdiffusion3 publicly available, with Krishna adding, “We’re really excited to see what everyone else builds on it.”

Despite the steady stream of breakthroughs and publications emerging from the Institute for Protein Design, Baker acknowledges that the path to success is rarely straightforward. “It all sounds beautiful and simple at the end when it’s done,” he reflects. “But along the way, there’s always the moments when it seems like it won’t work.” Nevertheless, the researchers persist, continually finding ways to overcome obstacles and advance the field. The institute also plays a crucial role in training the next generation of protein scientists, with many graduates and postdoctoral fellows going on to launch companies or establish their own academic labs.

The excitement surrounding these developments is palpable, with Baker comparing the experience to riding a wave: “I don’t surf, but I sort of feel like we’re riding a wave and it’s just fun. I mean, it’s so many, so many problems are getting solved. And yeah, it’s really exhilarating, honestly.” This enthusiasm reflects the transformative potential of these AI protein design tools, which are rapidly closing the gap between human-engineered proteins and those shaped by billions of years of natural evolution. As these technologies continue to evolve and become more accessible to the broader scientific community, we may be witnessing the dawn of a new era in protein engineering—one where custom-designed proteins could address some of humanity’s most pressing challenges in medicine, energy, and environmental sustainability.