The Rise of AI Assistants: From Personal Projects to Professional Tools

In the quiet hours of a Friday afternoon, Diego Oppenheimer receives an email that has become essential to his professional life. This weekly digest summarizes his meetings, inbox conversations, and calendar commitments, distilling a week’s worth of information into actionable insights. What makes this tool remarkable isn’t just its functionality, but its origin – Oppenheimer built it himself. The Seattle-based entrepreneur and former co-founder of Algorithmia created “Actionary” as a personal experiment to test whether he could still code after years away from hands-on development. With the help of AI coding assistants, he crafted what he humorously describes as 40,000 lines of “spaghetti code” that, despite its messiness, delivers substantial value. “It gives me a superpower,” Oppenheimer explains, highlighting how the tool remembers what he forgets and flags commitments he needs to address. His creation represents a growing trend of individuals and organizations offloading certain types of judgment and workflow to autonomous systems – software designed to analyze data, make recommendations, and sometimes act independently.

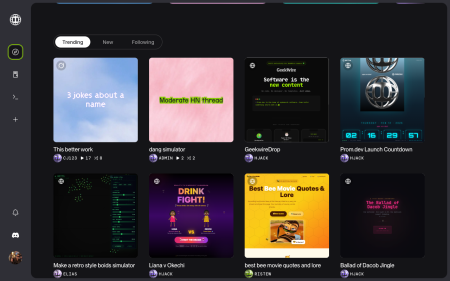

This emerging frontier of AI agents represents a significant shift in how we approach productivity and assistance. T.A. McCann of Pioneer Square Labs envisions a future where people might employ specialized agents for distinct tasks – travel planning, financial management, health coaching, and more – potentially coordinated by a higher-level AI functioning as a personal chief operating officer. The market reflects this vision, with projections showing growth from $3.3 billion this year to over $21 billion by 2030. Both enterprise giants like Microsoft and Salesforce and innovative startups are driving this expansion by embedding agents into workplace software. However, defining what constitutes a true “AI agent” remains contentious. Oppenheimer maintains that genuine agents require both autonomy and independent decision-making capabilities – a standard his own system doesn’t fully meet. “If you asked a marketing department, they would say, absolutely, this is fully agentic,” he notes with a hint of technical purism. “But if I stick to my AI nerd cred, is there autonomous decision-making? Not really.”

Seattle-based Read AI represents one of the companies exploring this technological frontier. Known for its AI meeting summarization and analysis tools, the company has raised over $80 million in funding and has been internally developing an AI executive assistant called “Ada.” CEO David Shim revealed that Ada can handle scheduling meetings and responding to emails – sometimes so quickly that the team has intentionally built in delays to make responses feel more natural to recipients. Shim has pushed the technology’s boundaries by giving Ada access to workplace data from various platforms and allowing it to autonomously answer investor questions about Read AI’s business. “It answers questions that I would not have the answer to right off the bat,” Shim notes, explaining that Ada draws from both his data and his team’s collective information. However, Ada still struggles with complex multi-person scheduling and occasionally “hallucinates” information. To address these limitations, Read AI incorporates human oversight mechanisms, including “sidebars” where Ada requests confirmation before sending potentially sensitive replies.

The challenge of creating effective AI assistants becomes particularly evident when examining specific use cases like travel planning. Brad Gerstner, founder and CEO of Altimeter Capital, proposed a simple benchmark: can an AI agent book a specific hotel on a given date at the lowest price? “Until we can do that, we have not built a personal assistant,” Gerstner stated. This challenge was addressed by Otto, a startup focused on business travel assistance. When tasked with booking the Mercer Hotel in New York at the lowest rate, Otto successfully completed the task in about two minutes. The system’s sophistication comes from its architecture – rather than using a single monolithic model, it coordinates multiple specialized agents handling different aspects of the travel process. Otto learns detailed user preferences, from preferred amenities to loyalty programs, using this knowledge to refine searches and provide personalized recommendations. Interestingly, though the system could theoretically complete bookings autonomously, it confirms details with users before finalizing purchases – a precaution that founder Michael Gulmann describes as psychological rather than technical, acknowledging that most people aren’t yet comfortable with AI making purchases without their explicit approval.

If hotel booking represents an acid test for autonomous assistants, meeting scheduling represents the everyday challenge that many professionals would gladly offload. Seattle startup Howie tackles this problem with an AI assistant that lives in email. By simply CCing Howie on an email thread, it proposes meeting times, confirms with all participants, creates calendar invites, and adds meeting links. Working from detailed preference documents that specify acceptable meeting venues, time constraints, and other parameters, Howie aims to replicate how experienced executives train their human executive assistants. With $6 million in funding and growing customer adoption, the company employs a hybrid model that combines AI with human oversight to prevent small but consequential errors like timezone confusion or misreading social cues. “If you think about the things that a great human EA does, software is not replacing that anytime soon,” notes Howie co-founder Austin Petersmith. Interestingly, many of Howie’s users are human executive assistants themselves, who use the tool to offload logistics so they can focus on higher-value activities.

For Diego Oppenheimer, the value of AI assistance is deeply personal. Self-described as “extremely calendar dyslexic,” he previously relied on human executive assistants to prevent him from triple-booking himself or traveling to the wrong cities. When he stepped back from full-time company leadership, hiring someone solely to manage his complex schedule no longer made financial sense – thus prompting his creation of Actionary. While his project won recognition at an AI Tinkerers event, Oppenheimer emphasizes it’s a personal tool, not a commercial product. He remains optimistic about the broader trend of AI assistance but recognizes current limitations. Today’s AI agents excel at narrow, well-defined tasks but struggle with broader human judgment. The consensus among experts suggests that attempts to create all-purpose digital assistants often encounter the boundaries of current AI capabilities. As David Shim argues, “The approach of agents doing everything is not the right approach. If you try to do everything, you’re not going to do anything well.” Instead, the most successful implementations will likely focus on solving specific problems exceptionally well. For Oppenheimer and many others exploring this technology, the ultimate goal remains refreshingly straightforward: “I’m trying to make time in the day. That’s what I’m trying to do.”