A Paradigm Shift in Titan’s Hidden Mysteries

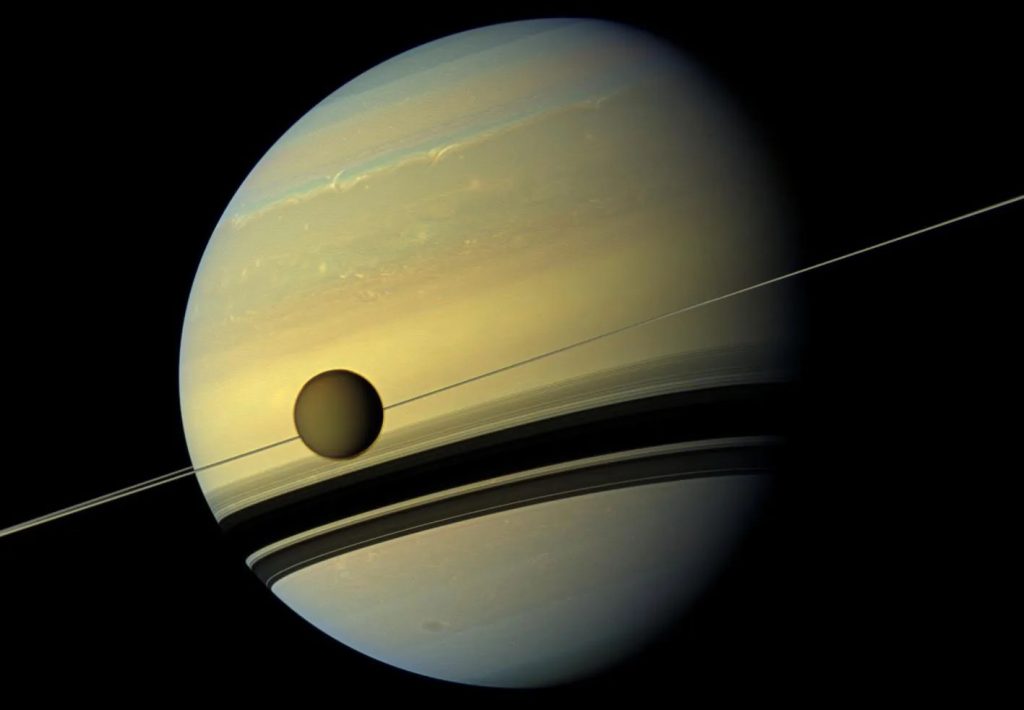

A striking image captured by NASA’s Cassini spacecraft shows Titan positioned dramatically against the backdrop of Saturn and its iconic rings, a visual reminder of this enigmatic moon’s place in our solar system. For years, scientists believed that beneath Titan’s thick, cloudy atmosphere lay a global ocean of liquid water, hidden under a shell of ice. This hypothesis, born from Cassini’s extensive observations between 2004 and 2017, became scientific orthodoxy. However, a groundbreaking new analysis published in Nature challenges this long-held belief, suggesting something quite different about Saturn’s largest moon. Using improved techniques to reexamine Cassini’s radiometric measurements, researchers now propose that Titan lacks the substantial global ocean previously theorized. This unexpected finding represents what University of Washington planetary scientist Baptiste Journaux calls “a true paradigm shift” in our understanding of Titan’s interior structure.

The revised model presents Titan with an upper layer of low-pressure ice approximately 106 miles thick, transitioning into a 235-mile-thick layer of high-pressure ice below. This contrasts sharply with earlier theories that proposed a substantial liquid water layer sandwiched between different types of ice. When the analysis first suggested the absence of a global ocean, it prompted extensive discussion and multiple rounds of verification among researchers who were themselves surprised by their findings. “We were all surprised, to say the least,” Journaux admitted, acknowledging how the results contradicted conventional wisdom. The team’s thorough approach—seeking feedback from colleagues outside their group even before submitting for peer review—underscores the significance of their discovery and the careful scrutiny applied to findings that overturn established theories.

Despite the absence of a global ocean, the research brings encouraging news for those hoping to find extraterrestrial life on Titan. The analysis suggests that pockets of liquid water and slush could exist within and between the layers of ice, or between the deepest ice layer and Titan’s core. Journaux notes that even if only 1% of Titan’s hydrosphere contains liquid water, the volume would be comparable to Earth’s entire Atlantic Ocean. These potential water reservoirs wouldn’t be vast, open oceans but rather more concentrated environments that might actually be more hospitable to life. As ice freezes, it tends to exclude salts and other dissolved materials, meaning these slushy pockets would be “enriched in dissolved species and nutrients for life to feed on, as opposed to a dilute open ocean.” This characteristic could potentially create numerous small but nutrient-rich habitable environments throughout Titan’s interior.

If life does exist in these scattered aquatic habitats beneath Titan’s surface, it would likely resemble organisms found in sea-ice ecosystems on Earth. This insight helps scientists narrow down what biological signatures to search for and refines future exploration strategies. Titan remains fascinating beyond just its potential subsurface water—its surface features lakes of liquid ethane and methane, and its atmosphere is rich with hydrocarbons. Any life existing on Titan’s surface would need to be radically different from Earth life, possibly utilizing biochemistry based on hydrocarbons rather than water. NASA’s upcoming Dragonfly mission, scheduled to launch in 2028 and land on Titan in 2034, will provide valuable new data about both surface conditions and interior structure, helping to answer questions raised by this study.

The implications of this research extend beyond Titan to other icy moons in our solar system thought to harbor water reservoirs. Saturn’s moon Enceladus and Jupiter’s moons Europa, Callisto, and Ganymede all remain promising targets in the search for extraterrestrial life. These Jovian worlds will soon be studied more closely by the European Space Agency’s Juice spacecraft (launched in 2023) and NASA’s Europa Clipper (launched in 2024). Journaux believes that the team’s findings on Titan will help scientists better understand what to look for on these other icy worlds. “As our understanding of their interiors will become much more accurate and refined with upcoming missions,” he explained, “this result shows us how we can, with new measurements, place much stronger and more precise constraints on the types of habitable environments that may exist.”

The study, titled “Titan’s Strong Tidal Dissipation Precludes a Subsurface Ocean,” represents a collaborative effort led by Flavio Petricca of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, with contributions from scientists across multiple institutions. While challenging our previous understanding of Titan’s interior, it opens exciting new possibilities about how life might exist in discrete pockets rather than vast oceans. As Journaux emphasized, “The search for extraterrestrial environments is fundamentally a search for habitats where liquid water coexists with sustained sources of energy over geological time scales.” This research doesn’t eliminate Titan as a potential home for life—it simply reframes our understanding of what habitable environments on this fascinating moon might look like, offering what Journaux calls “strong justification for continued optimism regarding the potential for extraterrestrial life on Titan.” As missions like Dragonfly prepare to explore this mysterious world, scientists and space enthusiasts alike can look forward to new discoveries that may revolutionize our understanding of Titan and the potential for life beyond Earth.