Microsoft Workers and Protesters Clash Over Israel Ties, Office Occupation, and Firing of Employees

In the heart of Redmond, Washington, tensions have escalated dramatically between Microsoft and a group of protesters demanding the tech giant cut ties with Israel over allegations that its technology is being used against Palestinians in Gaza. The conflict reached a boiling point this week when several members of the group “No Azure for Apartheid” occupied Microsoft President Brad Smith’s office, leading to arrests and subsequent employee terminations. The incident has sparked intense debate about corporate responsibility, employee activism, free speech, and the ethical use of technology in conflict zones.

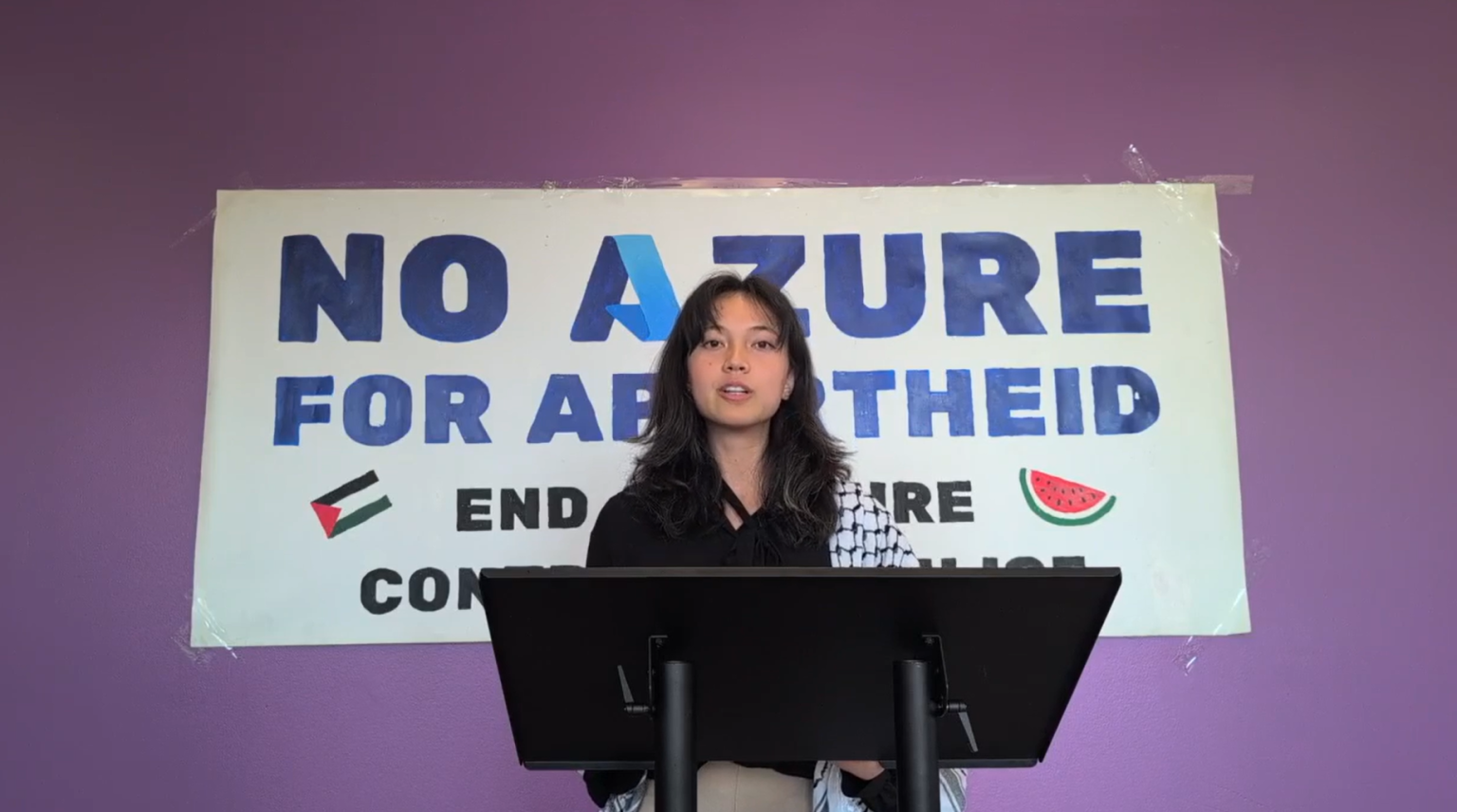

The confrontation began when seven protesters entered Microsoft’s headquarters building and made their way to Brad Smith’s office, where they locked arms, chanted “Free Palestine,” livestreamed their actions on Twitch, and barricaded the door while demanding talks with company leadership. According to Microsoft, the protesters “stormed” the building and created significant safety concerns, while the protesters themselves describe their sit-in as “completely nonviolent.” The situation escalated when Redmond police removed and arrested the seven individuals on charges including trespassing, obstruction, and resisting arrest. In the aftermath, Microsoft fired four employees connected to recent protests, citing “serious violations of established company policies and code of conduct.” Among those terminated were Anna Hattle and Nisreen Jaradat, who later spoke at a press conference challenging the company’s version of events.

One particularly contentious point revolves around what Microsoft described as “listening devices” allegedly left behind by protesters. Brad Smith referenced these devices in his comments following the incident, but protest leader Hossam Nasr strongly disputed this characterization, stating, “As Brad himself admits, if someone were to plant listening devices, this is not how they would do it. If anything, we would like our phones back, please.” This disagreement highlights the deeply divergent narratives between the company and protesters about what actually transpired during the occupation. The protest was not an isolated incident but part of an escalating campaign that included an earlier demonstration the previous week where twenty protesters were arrested after refusing to disperse from an encampment they created in front of the Microsoft sign, which they covered in red paint to symbolize blood.

The protesters’ core demand is for Microsoft to end all contracts with Israel, particularly those involving its Azure cloud platform, which they allege is being used by the Israeli military for surveillance and operations in Gaza. Microsoft has maintained that it found no evidence its technologies were used to harm civilians, though it acknowledged limitations in what it could verify given its lack of visibility into how its technology is used on private servers outside its cloud. The company recently launched a new investigation following a report from The Guardian alleging that Azure was used by the Israeli military for mass surveillance in Gaza. Brad Smith acknowledged that The Guardian “did a fair job in its reporting” and that while some information was false and some true, “much of what they reported now needs to be tested.” The protesters, however, rejected another investigation as insufficient, demanding immediate termination of all contracts and reparations to the Palestinian people.

At the heart of this conflict lies a fundamental disagreement about the effectiveness of internal dissent and the corporate response to employee concerns. Smith has emphasized that Microsoft has a “culture of trust with our employees” and that executives read and take employee feedback seriously, suggesting that protests are “not necessary in order to get us to pay attention.” He further noted that such disruptions distract from the dialogue the company is having with internal groups of different backgrounds, faiths, and cultures, including Palestinian allies. However, the protesters directly challenged this assertion during their Thursday press conference, with Anna Hattle stating that a petition with more than 2,000 employee signatures demanding the company cut ties with the Israeli military was sent to every Microsoft executive in May and received no response. Nisreen Jaradat went further, alleging that Microsoft Security specifically targeted protesters carrying the scroll of petition signatures and tore it during one protest, suggesting a pattern of suppression rather than open dialogue.

The broader context of this confrontation cannot be overlooked. Smith acknowledged the human toll of the conflict in the Middle East, citing the 1,139 people killed in the October 7 Hamas attack in Israel and the 61,000 civilians who have died in Gaza. He described Microsoft’s role as “to provide technology in a principled and ethical way” while upholding its human rights principles and terms of service. Meanwhile, the protesters argue that the company is complicit in what they describe as apartheid and genocide through its technology partnerships with Israel. This fundamental ethical disagreement has now spilled over into questions about employee rights, corporate governance, and the boundaries of workplace activism. As Microsoft continues its investigation and works with law enforcement, the terminated employees and their supporters remain undeterred, turning what began as a protest about international affairs into a complex domestic confrontation about the responsibility of tech companies in global conflicts and the rights of workers to voice political dissent.