The Rise and Fall of Outbound Aerospace: A Startup’s Journey

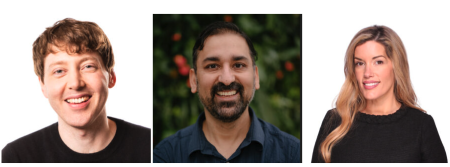

In the ever-competitive landscape of aerospace innovation, Seattle-based Outbound Aerospace briefly soared with promise before an abrupt descent. Just months after raising more than $1 million in pre-seed funding and successfully testing a prototype for a revolutionary blended-wing passenger jet, the startup faced the harsh reality many ambitious ventures encounter. Jake Armenta, co-founder and chief technology officer, announced the company’s closure on LinkedIn with a touch of humor, joking that competitors like Boeing “who have been rightly terrified of us” might celebrate the news. Behind this lighthearted farewell lay a more sobering truth that Armenta later shared with GeekWire: “The simplest answer is that we ran out of money, and hadn’t really secured customer commitments that were strong enough to secure the next stage of investment.” Their story reflects the precarious journey of aerospace startups navigating between bold visions and market realities.

Outbound Aerospace found itself caught in a strategic crossroads that ultimately contributed to its downfall. The company had initially set out to revolutionize commercial aviation with an innovative passenger aircraft design, but gradually pivoted toward developing military drones—a common shift among aerospace startups as defense opportunities expand in areas like missile defense, next-generation drones, and hypersonic vehicles. “We didn’t really plan on being a military vendor,” Armenta explained, though his background at Boeing Phantom Works gave him insight into government needs. This expertise helped the team develop the Gateway UAV, closely resembling their 22-foot-wide blended-wing prototype tested in March. The drone was designed to carry deployable “mission containers” for cargo or national security sensor missions, attracting significant interest from potential military customers. However, this interest didn’t translate quickly enough into contracts or funding.

The financial constraints that ultimately grounded Outbound reveal the chicken-and-egg dilemma faced by many deep-tech startups. Despite raising $1.3 million—including $500,000 each from Blue Collective and Antler, with the remainder from smaller investors—the company found itself in a catch-22 situation. CEO Ian Lee described their predicament perfectly: “We got stuck with DoD customers who were saying, ‘Hey, this is amazing. We want to see it demoed. And then we can write a contract, and contract equals dollars.’ So, then we turned around and went to the investment community and said, ‘They want to see a demo, and we need to raise [money] to do that.'” This created an impossible situation where they needed money to demonstrate capabilities that would earn them contracts that would then attract investors. Adding to this challenge, the pivot away from commercial aviation alienated early investors who “were really wanting to do big moonshot projects,” while military drone investors “wanted to see a lot more traction than we had,” according to Armenta.

Timing proved to be another critical factor in Outbound’s demise. Armenta reflected that their strategic shift came too late: “There’s a version of this where if we had decided early on, ‘Hey, we’re going to build a military drone first and put all of our effort into that’ … I think we would have been able to sell it without a problem in the time frame that we had. But we didn’t really decide that until midway through.” The irony was that just as Outbound was running on empty, public interest in their work was accelerating. The BBC featured the company alongside other blended-wing aircraft designers in a story about rising interest in such designs. Even two months before closure, Lee had posted on LinkedIn that he was “excited for y’all to see what’s next,” believing investment was imminent to support their Department of Defense work. “We had half of our round secured at that point,” Lee explained, “…I was expecting investment to come on pretty quickly and [we could] start talking about that publicly. It never came through.”

Despite the setback, both founders maintain optimism about the future of their concepts and their personal journeys in aerospace innovation. Outbound’s website still showcases the Gateway drone and their ambitious 254-passenger Olympic airliner, advertised as “coming in 2033.” Lee promised these concepts won’t be “disappearing into the ether,” while Armenta plans to continue discussing the five novel transport-category aircraft they designed. “I’m going to spend a little bit of time talking about those more publicly over the next couple of months. Maybe next year,” he said. Both founders are taking time to reflect and regroup—Lee through consulting and advising while taking “a pause on running a startup directly,” and Armenta by assisting friends in the aerospace industry while processing the experience. “We were a lot closer than we had any right to be,” Armenta reflected, noting the significant market hunger for new aircraft designs across commercial, military, and business sectors.

For Armenta especially, the closure represents a temporary setback rather than an end to his lifelong ambition. “This has been something that I’ve been wanting to do—literally—for 30 years,” said the 34-year-old, who recalls wanting to build aircraft since childhood. Rather than discouraging him, the experience at Outbound has strengthened his resolve. “Through this journey over the last couple of years, I saw a small, constrained number of errors that we made,” he observed. “I think that in the future, with a slightly different strategy, with all the knowledge and information and preparation that I have now… I’ll be back.” His parting message echoes the resilient spirit that defines entrepreneurs in the challenging aerospace sector—a determination to learn from failure and eventually reach new heights with refined approaches and hard-won wisdom.