From Rock Flipper to PFAS Fighter: Brian Pinkard’s Environmental Mission

In the summer of 2025, Brian Pinkard stood triumphantly on the summit of Washington’s Mount Shuksan. This achievement was symbolic of his life’s journey – tackling tough challenges head-on with determination and purpose. After earning his bachelor’s degree in mechanical engineering, Pinkard took an unusual detour. He spent six months “flipping rocks” in Colorado’s Rocky Mountains as part of an AmeriCorps program, clearing obstructions and building trails while living in a tent every night. This wasn’t just a break from his career path; it was a deliberate choice driven by his core values. “I loved it. It was great. And the reason I did that is because I wanted to do something that mattered, that made a difference in the world,” he explained. When the program ended, Pinkard was inspired to direct his talents toward larger environmental challenges, setting the stage for his remarkable journey from trail builder to scientific innovator tackling one of our planet’s most persistent pollution problems.

This passion to create positive change, combined with an engineer’s natural problem-solving instincts, propelled Pinkard to pursue a doctoral degree from the University of Washington. His academic path eventually led to the founding of Aquagga, a groundbreaking startup focused on destroying PFAS – a class of toxic pollutants commonly known as “forever chemicals.” His PhD advisor, Igor Novosselov, a research professor at the UW’s Department of Mechanical Engineering, recognized something special in Pinkard from the beginning: “Brian has been very laser focused on his mission. He’s not a typical scientist who would just go and write a bunch of papers. He’s going after impact where it matters.” This drive for real-world solutions over academic recognition would become a defining characteristic of Pinkard’s approach to science and innovation, though his journey to tackling PFAS pollution took some unexpected turns along the way.

Before setting his sights on forever chemicals, Pinkard was working on another daunting challenge – nerve gas in the Middle East. When he joined Novosselov’s lab, it had funding from the U.S. Department of Defense to develop a mobile strategy for treating abandoned chemical weapons in the Syrian desert. The existing solution was dangerous and inefficient – trucking barrels of deadly chemicals to the Mediterranean Sea, loading them onto boats, and incinerating them. “If you’re the guy who’s got to transport a nerve agent, it’s not a very good job,” Pinkard noted with characteristic understatement. Within five years, the lab successfully developed a workable solution. Although the DoD ultimately shelved its application of the technology as the immediate need subsided, Pinkard had glimpsed the tremendous potential of their approach for treating hazardous materials and began wondering about other possible applications.

As Pinkard was preparing to complete his PhD in June 2020, the COVID pandemic disrupted his plans to pursue a university postdoctoral fellowship when hiring freezes became widespread. Forced to pivot, he embraced entrepreneurship – a path he had never previously considered. Teaming up with engineer and tech innovator Nigel Sharp, they initially explored using their technology, called supercritical water oxidation, to treat sewage sludge from wastewater treatment plants. However, they quickly realized this market wasn’t viable. At the same time, they noticed growing concern about PFAS contamination. “Everybody was talking about PFAS,” Pinkard recalled, and the realization that their technology might offer a solution for destroying these seemingly indestructible chemicals became his entrepreneurial lightbulb moment. In 2019, Pinkard and Sharp founded Aquagga in Tacoma, Washington, soon joined by co-founder Chris Woodruff, and set out to adapt their approach specifically for PFAS destruction.

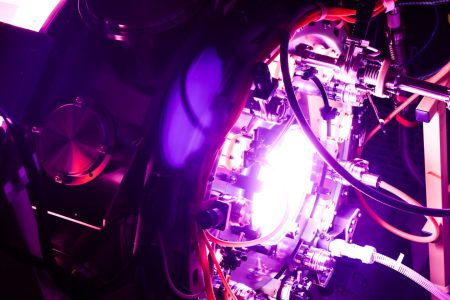

PFAS chemicals have been used for decades in everything from firefighting foams and food packaging to carpets, water-repellent clothing, and non-stick cookware. Their remarkable durability at repelling water, stains, and grease made them commercially valuable, but that same persistence has created a global environmental crisis. These chemicals escape from products and now contaminate drinking water nationwide, even appearing in mothers’ breast milk, raising serious health concerns among researchers and regulators. Aquagga’s innovation involves destroying PFAS under extreme conditions – super hot, high pressure, and highly caustic through the addition of lye. The company shifted to a technique called hydrothermal alkaline treatment, securing a patent for this approach from the Colorado School of Mines. Professor Timothy Strathmann from the school praised Pinkard’s scientific integrity: “Unlike many entrepreneurs I’ve interacted with, he is also deeply interested in understanding the limitations and technical challenges associated with the technology. He’s keenly aware that the long-term success of Aquagga will only be achieved by addressing the critical barriers to deployment.”

The journey from concept to real-world implementation has been impressive. Aquagga has conducted nine field demonstrations of its technology across diverse scenarios – from an airport in Alaska to a Department of Defense-funded project in North Carolina involving firefighting foams, and a wastewater demonstration with the City of Tacoma. As of this writing, the company stands on the verge of signing its first long-term commercial deployment, a milestone that Pinkard views with justified pride. Looking back on his unusual career trajectory – from rock flipper to nerve gas neutralizer to PFAS destroyer – Pinkard remains motivated by the tangible environmental impact of his work. “It’s really cool to see how much PFAS we’ve destroyed… even in our short journey,” he reflected. “And to think about where it could go, what it could enable at scale. So I’m very optimistic about Aquagga’s future. I’m very optimistic about the impact we could create, the lives we could save.” For this uncommon thinker, success isn’t measured in papers published or profits earned, but in the lasting environmental legacy his work might leave for future generations.