The Evolution of Windows: From Platform Pioneer to AI Launchpad

Microsoft’s journey with Windows has been remarkable, transitioning from a revolutionary graphical interface that transformed computing to now potentially becoming the foundation for AI’s next frontier. This evolution mirrors the company’s ability to adapt to changing technological landscapes while maintaining its core mission of making computing accessible and powerful.

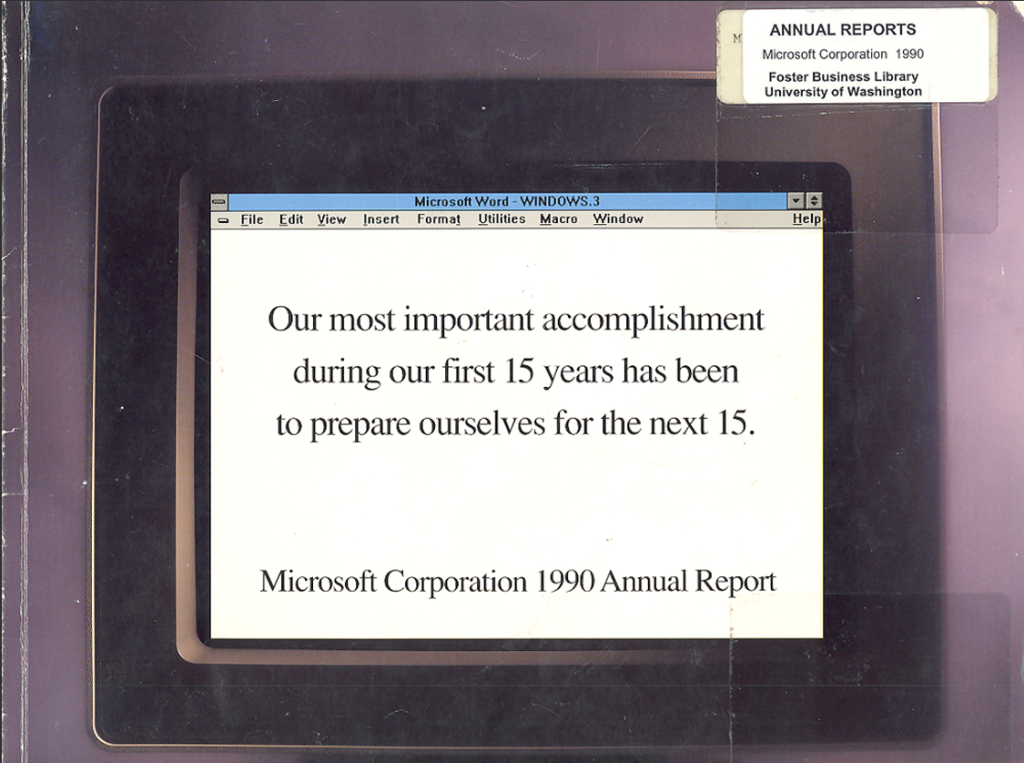

Back in 1990, Microsoft boldly claimed that the shift from MS-DOS to Windows was “like bringing a Porsche into a world of Model Ts.” This wasn’t mere marketing hyperbole. Windows 3.0 fundamentally changed personal computing by making third-party software easier to find and launch while offering developers a compelling value proposition: build to Microsoft’s specifications, and your software would become a “first-class citizen” on computers that were increasingly present in homes and offices worldwide. This symbiotic relationship between Windows as a platform and its ecosystem of applications became the engine driving Microsoft’s dominance in the following decades, establishing a virtuous cycle where more developers attracted more users, which in turn attracted more developers.

Fast forward 35 years, and Microsoft is attempting to replicate this successful platform strategy for the AI era with its new Agent Launchers framework. Recently introduced as a preview in Windows Insider builds, this framework allows developers to register AI agents directly with the operating system. These agents can appear in the Windows taskbar, inside Microsoft Copilot, and across various applications. The vision is ambitious: autonomous assistants operating directly on users’ machines, handling everything from routine document organization to complex tasks like resolving scheduling conflicts or compiling information across multiple applications for upcoming meetings. Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella has framed this as developing “rich scaffolds that orchestrate multiple models and agents” with memory and entitlements—essentially creating the sophisticated engineering infrastructure needed to derive real-world value from AI.

This integration of AI agents into Windows represents more than just feature addition; it’s a fundamental shift in how operating systems function and interact with users. Traditional applications ran in isolation, working with their own files and rarely interacting with the broader system. In contrast, AI agents need persistent memory and context awareness across applications to be truly effective. As Microsoft CTO Kevin Scott explained, “Agents are going to need to be able to scratchpad their work,” maintaining interaction history and accessing necessary context to solve problems effectively. This deeper integration creates unique security challenges that Microsoft is addressing through a security framework that runs agents in contained workspaces with limited access to user folders. The company acknowledges these risks, advising users to understand the security implications before enabling agents and keeping these features off by default.

However, today’s competitive landscape differs dramatically from the 1990s when Windows became the dominant computing platform. The modern computing ecosystem is fragmented across smartphones, browsers, and cloud platforms—areas where Microsoft doesn’t always hold the advantage. While the company maintains strong footing in enterprise computing through Azure, Microsoft 365 Copilot, and business-focused agents, the Agent Launchers initiative represents a different bet: making Windows the home for agents serving individual users on their personal machines. This is a more challenging proposition when PCs must compete with phones, browsers, and cloud apps for users’ attention and loyalty. Unlike in the 1990s, Microsoft cannot simply build the platform and expect developers and users to flock to it automatically.

There’s also growing skepticism about Microsoft’s motivations for integrating AI capabilities into Windows. Critics suggest these features are being introduced not primarily because users want them but because Microsoft needs to justify its massive AI investments and drive revenue growth. Ed Bott, a longtime tech journalist and Microsoft observer, noted that “They’re thinking about revenue first and foremost,” suggesting that increased user reliance on AI features makes it easier for the company to upsell premium services. This business imperative is understandable when examining Microsoft’s financial reality: Windows and Devices generated $17.3 billion in revenue in the most recent fiscal year—essentially flat for three years and now less significant than Gaming ($23.5 billion), LinkedIn ($17.8 billion), and far behind Azure’s cloud services ($98 billion) or Microsoft 365 commercial ($88 billion). This stands in stark contrast to fiscal 1995, when Microsoft’s platforms group represented about 40% of its $5.9 billion total revenue.

As Microsoft navigates this transition, the stakes are high but so is the potential reward. Windows is unlikely to regain its once-dominant position in Microsoft’s portfolio, but AI integration represents the company’s best strategy to revitalize the operating system and ensure its continued relevance. Whether this transformation ultimately resembles “a restored Porsche or a rocket ship on the launchpad” may matter less than keeping Windows from becoming obsolete in a rapidly evolving technological landscape. The question now is whether Microsoft can successfully position Windows as the natural home for AI agents in the same way it once became the default platform for applications, convincing both developers and users that an AI-integrated Windows offers unique value that standalone agents or cloud services cannot match.