Imagine this: You’re bundled up in layers of wool and fur, your breath freezing in the frigid air of North Karelia, a rugged Finnish region tucked right against the Russian border. Winters here are a relentless embrace of cold, stretching for months on end, where the sun barely cracks the horizon and the snow piles knee-deep in drifts. In the dead of this season, locals like me find solace—or at least a way to kill time—by settling onto the icy expanse of a frozen lake, fishing rod in hand, drilling holes through thick ice to dangle lines into the dark, frigid waters below. It’s a solitary pursuit on the surface, but one laden with quiet anticipation. As I sit there, bundled against the biting wind, the real challenge isn’t the catch; it’s deciding how long to hunker down in that snug spot before mustering the willpower to brave the fierce gusts, plow through the powdery snow, and trek to a new hole or even a neighboring lake. It’s like weighing a warm fire against the uncertainty of the unknown—should I stay or should I go? This decision-making dance mirrors ancient subsistence tactics, where our ancestors had to mentally tally the worth of a gathering spot, be it scavenging berries on a bush, digging for roots in fertile soil, or luring elusive fish beneath a blanket of ice. Across millennia, humans have fine-tuned this instinct: collect what you can in one patch before expending precious energy to seek fresher pastures. It’s survival math, really, etched into our DNA from eras when food wasn’t a sure thing. Yet, as captivating as it is to think of foraging in this raw, elemental way, it also stirs a deeper wonder about how we’ve navigated such harsh environments, evolving not just physically but mentally to thrive amidst the freeze. This winter ritual isn’t just about fish; it’s a living relic of our adaptive brilliance, reminding us how intimately tied we are to the land and each other in the face of nature’s unyielding chill.

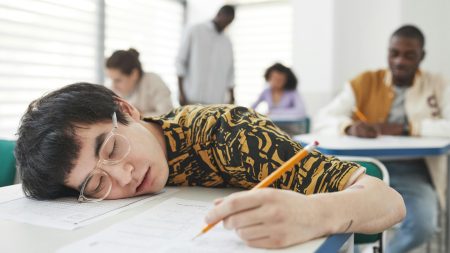

Diving into the science of this icy pastime reveals layers as deep as the lake itself. Traditional research on human foraging often paints it as an individual endeavor, influenced heavily by personal know-how—decisions rooted in one’s experience of what works. But much of this work has been sculpted in controlled settings, like labs where solo gamers chase virtual resources on screens, far removed from the elements. It’s easy to forget that in the real world, foraging—or fishing, in Karelia’s case—is rarely a lone wolf affair. Groups cluster, sharing not just space but unspoken signals about the bounty beneath the ice. Picture it with me: a dozen bundled figures hunched over their holes, not chatting much, perhaps out of rivalry or sheer focus, but their presence alone speaks volumes. They’re tuning into collective wisdom, leaning on the crowd’s success as a beacon. Recent studies, as fascinating as they are counterintuitive, show that this social aspect is key. Going it alone might offer independence, but there’s real power in the pack—the “wisdom of the group,” as psychologists call it. In environments as unforgiving as the Arctic, where missteps can cost dearly, mimicking others isn’t blind following; it’s a smart shortcut, a way to hedge bets in a game where the rules are as slippery as the ice. Researchers like Alexander Schakowski, a sharp-minded psychologist from Berlin’s Max Planck Institute, have unearthed that fishers, especially those nursing poor luck, ditch isolation to join clusters more frequently than not. It’s a blend of skepticism and trust—the gut instinct versus the crowd’s call—highlighting how our brains juggle solo smarts with social cues. This dance reveals evolutionary threads, suggesting intelligence wasn’t just honed in solitude but through the intricate web of human connections, where one person’s insight saves another’s hide in the wild’s embrace.

Unpacking these decisions in extreme climes, from sweltering tropics to bone-chilling poles, offers tantalizing glimpses into our past and present. Schakowski’s insights hint at the origins of complex thought, proposing that intelligence blossomed not only from individual trials but from observing and adapting to peers. Imagine the first explorers in prehistoric frost, learning swiftly that banding together wasn’t just for warmth but for wealthier hauls. “This peels back the veil on the drivers of intelligence,” echoes behavioral ecologist Friederike “Freddy” Hillemann from Durham University, her excitement palpable even across her research on animal foragers. In Karelia, this manifests in contests that feel like modern echo of ancient rites—tournaments where ice fishing for subsistence has morphed into sport, drawing crowds of enthusiasts amid the Nordic charm. These events, hosted in Northern Karelia’s snowy arenas, attract thousands, transforming quiet subsistence into competitive thrill. Raine Kortet, an aquatic ecologist from the University of Eastern Finland, embodies this shift; an avid fisher himself, he recruited the region’s elite anglers, including thirty-one regulars across ten tournaments in 2022 and 2023. It was a natural experiment, one that let researchers peekInto authentic decision-making, far from sterile labs. Schakowski, admitting his own clumsiness on the ice—”I tried it once, not successful, clueless with a catch”—grinned through the process, his team’s work underscoring how extreme settings test and reveal our cognitive gears. By observing these contests, they uncover patterns: cracks in the ice of solo reliance, where loneliness gives way to communal pull. It’s human nature at its most elemental, where even in sport, the echoes of survival resound, teaching us about mental evolution amidst the freeze.

Now, picture the scene from those tournaments, brought to life through vivid details that make the science pulse with realness. Seventy-four anglers, rigged with GPS trackers and head-mounted cameras, ventured out for three-hour sprints to net as many kilograms of perch as possible, lured by cash prizes and the sweet sting of victory. The rules were simple yet taut: fifteen minutes to scout the initial spot, most abandoning dud holes after mere minutes of silence. But as the ice hummed with activity, clusters formed—groups of five to ten, backs turned in wary solitude, guarding their catches like treasures in a greedy quest. These weren’t cheerful gatherings; tension laced the air, voices scarce, yet the collective presence dictated moves. Video footage, painstakingly analyzed, revealed the heartbeat of their strategy: fishers stayed put or bolted based on personal triumphs, clinging to spots yielding bites while ditching the barren. Yet, when luck waned, the allure of the crowd proved irresistible—they edged closer, merging into packs that promised better odds. Environmental factors, like favoring steep lakebed contours where perch might huddle for sanctuary, took a backseat, overshadowed by social dynamics in this leveled landscape. Schakowski notes this might differ in varied terrains, but here, on Northern Karelia’s forgiving lakes, human patterns reigned supreme. It’s a reminder that foraging isn’t just about nature’s whispers; it’s about our own signals, the silent agreements forged in frost that guide paths forward. Far from anonymous data, these stories humanize the study, showing anglers as thinkers, innovators navigating ice with the same flair as our forebears, their decisions a tapestry of instinct and observation that feels achingly familiar.

Delving deeper, anthropologist Michael Gurven from UC Santa Barbara captures the essence with folksy wisdom: “We’re social creatures, constantly glancing over shoulders to see what others are up to.” This mirrors the Karelian clusters, where lone wolves yield to packs, not out of weakness but pragmatism in a hostile domain. Gurven and Hillemann alike urge expanding the lens—interviewing these fishers to unearth their narratives, bridging science with story. Unlike observing beasts in forests, here we can converse, probing the “why” behind switches from solitude to swarm. One fisher might recount the crunch of snow under boots as he chose a crowd, buoyed by strangers’ success; another the pang of isolation, spurring a join-the-flock moment. These voices add flesh to data, transforming cold facts into warm anecdotes. For instance, envision Kortet, the local expert, recalling childhood hauls or tournament thrills, his passion painting personal histories onto evolutionary canvas. Schakowski’s admission of his fishing flop—that hilarious humility—mirrors how even experts learn from immersion, appreciating the cultural weave. Future studies could explore gendered choices or cultural norms, enriching our understanding. Ultimately, this work privileges human essence, showing foraging as communal ballet, where spikes in catches draw near like moths to flame. It’s not just survival; it’s connection, the shared pulse that powered our species through millenniums of chill and change.

Reflecting on it all, this Karelian saga invites us to ponder broader horizons beyond icebound lakes. The balance of personal instinct and group wisdom isn’t confined to fishing—it’s woven into daily life, from office decisions to social media trends. Schakowski’s findings affirm that in adversity, humans lean on peers, evolving deftness in thought that outpaces individual paths. With Hillemann’s nudge for dialogue, the narrative grows richer, revealing how extreme feats foster innovation. Imagine extending this to global forages—tropical fruit glens or desert water hunts—adapting the Karelian model. Economists, ecologists, even game designers could glean lessons from these clusters, crafting strategies that honor both self and society. Sponsorship buzz and academic buzz alike fade before the true gift: empathy for our adaptive selves. In humanizing this research, we see not lab rats but resilient kin, their icy pursuits echoing our quest for belonging amidst the unknown. As winters endure, so does our ingenuity, a flame lit by collective spark in the darkest freeze. This story, drawn from Karelia’s heart, warms the soul, urging us to embrace both solitude’s clarity and the crowd’s embrace in our endless hunt.