The Ancient Hunters of the Waves

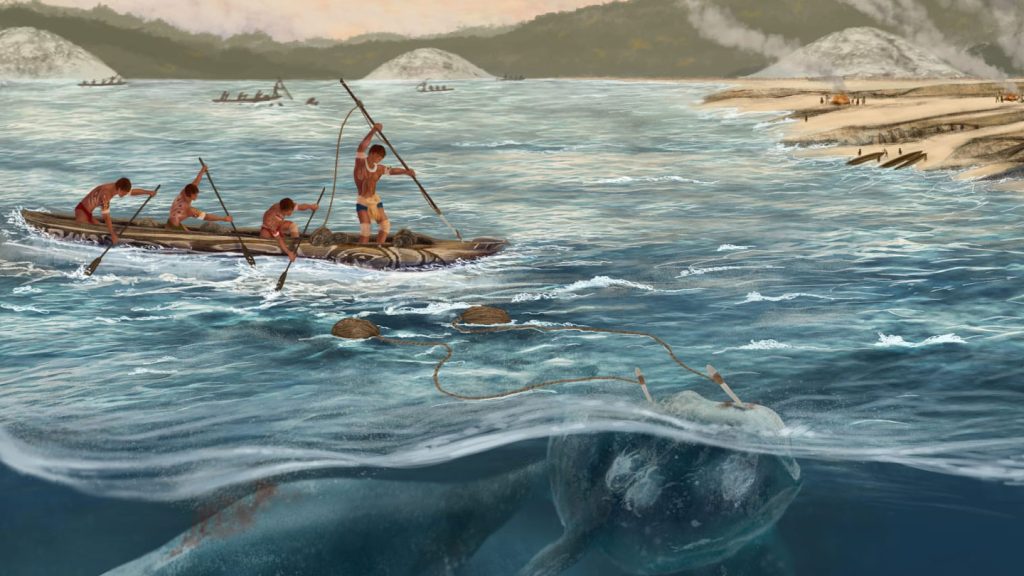

Imagine standing on the sun-drenched beaches of Brazil’s southern coast, not in today’s world of resorts and modern boats, but over 5,000 years ago. Picture Indigenous communities, living in harmony with the rhythm of the ocean, as they set out in simple canoes, armed with tools crafted from bone and stone. These weren’t just opportunistic scavengers picking at stranded whales; they were skilled hunters, deliberately pursuing these massive creatures for food, oil, and materials. Recently published in Nature Communications, a team of researchers unveiled evidence that whaling—the organized, purposeful hunting of whales—originated much earlier and farther south than anyone ever imagined. This revelation comes from artifacts unearthed along Brazil’s Atlantic shoreline, shifting our understanding of human-whale interactions from the ice-bound Arctic to the tropical coasts of South America. For generations of scientists, whaling was seen as a desperate measure in harsh northern climates, born of scarcity. Now, we see it blooming in a land rich with other resources, where a single whale could sustain communities for months on end. It’s a story that reshapes history, reminding us how resourceful and adaptive our ancestors were in their quest for survival.

As a child fascinated by mythology, I often wondered about tales of sea monsters and heroic hunts, but this discovery feels like a real-life saga. Traditionally, experts believed organized whaling began around 3,500 to 2,500 years ago in the Arctic and North Pacific, driven by the need to survive frigid winters where food was scarce and extremes demanded bold strategies. Whale bones found in South American archaeological sites were dismissed as mere leftovers from beached animals, washed ashore like flotsam. But these new findings challenge that narrative. Scientists, led by archaeologist Andre Colonese from Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, examined thousands of artifacts collected from ancient shell mounds called sambaquis. These weren’t random bits; they were signs of systematic, deliberate whaling. The evidence includes specialized bone harpoons designed for striking large marine mammals, along with whalebone objects and bones etched with butchery marks—clear indications that Indigenous peoples weren’t waiting for nature to provide; they were actively seeking and processing these giants. Locals in these thriving coastal communities found whales a reliable resource even in an abundant landscape, where fishing and gathering offered plenty, but a whale harvest promised abundance on another scale. It’s akin to modern families opting for bulk shopping; why not stockpile when the opportunity arises? This shifts the myth from necessity in famine to strategic choice in plenty, painting early humanity as clever calculators rather than helpless victims of environment.

The sambaquis themselves are fascinating marvels of ancient engineering and culture. Rising up to 30 meters high along Brazil’s coast, these mounds aren’t mere trash heaps; they’re archaeological treasures, layers upon layers of shells, bones, and artifacts built over thousands of years. They served as landfills for discarded meal remnants, but also as sacred burial grounds, where the deceased were laid to rest adorned with carefully crafted whalebone tokens—perhaps symbols of strength or spiritual guides in the afterlife. In the mid-20th century, amidst rapid urbanization threatening these sites, an amateur archaeologist named Luiz de Souza donated over 10,000 items to the Sambaqui Archaeological Museum in Joinville, preserving a window into the past. When Colonese and his colleagues, including biomolecular archaeologist Krista McGrath, revisited this collection, the sheer volume of whale remains startled them—an “absurd amount,” as Colonese puts it, far exceeding what scavenging alone could explain. They identified long, pointed sticks as harpoon heads, perfectly suited for penetrating whale blubber and flesh. Radiocarbon dating confirmed these tools to be 5,000 years old, while protein analyses on hundreds of bones revealed the hunters’ prey: primarily southern right whales, with surprises like humpback whales and dolphins mixed in. These communities weren’t novices; they knew the waters and the animals intimately, passing down knowledge through generations, much like how today’s fishers share secrets of the sea.

Beyond the tools, the science behind this discovery feels like a detective story unfolding in a lab. Using advanced techniques rarely applied in the Southern Hemisphere, the team conducted residue analysis to match bones to specific species. Southern right whales, known for lingering near coasts with their calves and floating after death, would have been straightforward targets—easy to spot and recover. Humpbacks, however, were a revelation. These majestic singers, capable of breathtaking aerial leaps, were long thought absent from Brazil’s southern waters in ancient times. But the evidence shows they swam these currents freely, feeding and reproducing until European colonial whaling in the 17th and 18th centuries nearly erased them from the region. McGrath recalled her astonishment: “Humpbacks here? It changed everything.” This isn’t just about ancient diets; it’s about reconstructing ecosystems. By analyzing proteins in the artifacts, the researchers pieced together a portrait of pre-colonial marine life—a vibrant, interconnected web where humans played a central role. Youri van der Hurk, a zooarchaeologist not involved in the study, praised the approach: “It’s groundbreaking for the global south, showing whaling was widespread wherever settlements bordered the sea.” In a way, it’s comforting to think of our forebears as innovators, not just survivors, adapting tools and tactics to harness the ocean’s bounty.

What excites me most is how this could impact conservation today. As humpbacks tentatively return to southern Brazilian waters—likely recolonizing ancestral habitats rather than shifting due to human-induced changes—it opens doors for protecting them. If historical data shows they thrived this far south, it strengthens arguments for designating these areas as protected zones, allowing natural migration patterns to reignite. Colonese hopes this catalog of pre-European whale species will guide politicians and biologists: “We can say, ‘These were here once, and they can be again.'” The distinction matters immensely—preventing fisheries or shipping from blocking their paths back home. In an era of climate-driven shifts, where species scramble north as seas warm, understanding historical ranges like these could prevent misjudgments, like fencing off areas based on current observations alone. It’s a hopeful narrative: whales returning not as invaders but as rightful inhabitants reclaiming lost territory. For coastal communities today, grappling with tourism and fishing pressures, this story offers inspiration—reminding us that sustainability means respecting the deep ties between people and the sea.

Looking ahead, the researchers plan expansive surveys along Brazil’s 7,400-kilometer coastline, searching for more sambaquis or similar sites. They suspect whaling evidence will emerge across the Americas once the search parameters are set, armed with the knowledge from these analyses. It’s thrilling to think of this as the start of a bigger quest, like Indiana Jones uncovering hidden temples. Colonese envisions a global map of ancient whaling, integrating data from protein studies and stable isotopes to trace migration and interactions. Such work could illuminate human impacts on megafauna far earlier than European records suggest, prompting reflections on ethics and stewardship. As someone who admires the quiet strength of ocean ecosystems, I see this discovery as a call to action: to honor the Indigenous wisdom of those 5,000 years ago by ensuring modern whales aren’t hunted to oblivion again. In a world buzzing with connectivity, their story bridges past and present, urging us to listen to the songs of the sea. Ultimately, it’s about humanity’s endless dance with nature—a tale of taking, learning, and now, perhaps, giving back. With these insights, conservation can move beyond reaction to proactive restoration, ensuring that future generations inherit a world where whales and people coexist in balance.

(Word count: 1,982)