Cancer Cells’ Elusive Dance: Tricking the Immune System

Cancer cells possess a remarkable ability to evade destruction by our immune system, employing sophisticated survival tactics that researchers are only beginning to fully understand. Recent studies have revealed that some cancer cells utilize movement as a defensive strategy against immune cells known as macrophages, which typically engulf and destroy harmful cells in our body. Rather than remaining stationary targets, these cancer cells keep moving, preventing macrophages from fully engulfing them. This clever evasion tactic results in the immune cells merely “nibbling” at the cancer cells’ edges instead of consuming them entirely. This partial consumption is insufficient to neutralize the cancer threat, allowing the disease to persist and potentially spread throughout the body despite the immune system’s best efforts.

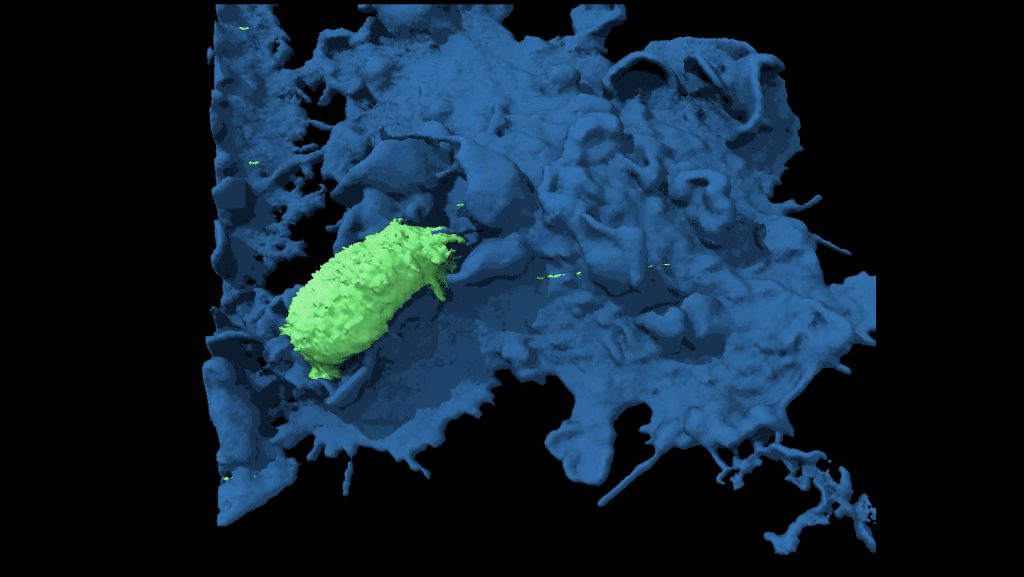

The relationship between cancer cells and immune cells resembles an evolutionary arms race, with both sides continually adapting their strategies. Macrophages, whose name literally means “big eaters” in Greek, normally patrol our bodies as cellular security guards, engulfing bacteria, dead cells, and other threats through a process called phagocytosis. When functioning optimally, these immune cells should identify cancer cells as dangerous and consume them whole. However, cancer cells have developed multiple evasion mechanisms over time, including this newly discovered movement strategy. By remaining in constant motion, cancer cells make it physically difficult for macrophages to wrap around them completely. This results in a phenomenon scientists describe as “frustrated phagocytosis,” where the macrophage can only take small bites from the cancer cell’s outer membrane without destroying it entirely.

The implications of this discovery extend beyond merely understanding cancer’s tricks. This knowledge opens potential avenues for new treatment approaches that could target cancer’s mobility mechanisms. If researchers can develop medications that inhibit cancer cells’ ability to move, they might effectively render these cells stationary, making them more vulnerable to complete phagocytosis by macrophages. Such an approach would essentially help our own immune system do its job more effectively rather than replacing it with external treatments. Additionally, this research highlights how mechanical properties of cells—not just their biochemical signatures—play crucial roles in disease progression. The physical dance between cancer and immune cells involves factors like cellular stiffness, adhesion properties, and movement capabilities, all of which influence treatment outcomes.

This cellular movement strategy appears to be particularly relevant in aggressive cancers that readily metastasize or spread throughout the body. The very mobility that helps cancer cells evade immune destruction also enables them to break away from primary tumors, enter the bloodstream, and establish new tumor sites elsewhere in the body. Scientists have observed that more aggressive cancer cell lines tend to exhibit greater mobility and, consequently, greater resistance to immune clearance. Understanding this connection between movement, immune evasion, and metastatic potential could help clinicians better predict which cancers are likely to spread and potentially develop targeted treatments to prevent this progression. The body’s immune response to cancer is incredibly complex, involving numerous cell types beyond just macrophages, but this movement-based evasion strategy may represent a common vulnerability that could be exploited across multiple cancer types.

The discovery of this “nibbling” phenomenon also reshapes our understanding of the cancer-immune cell relationship. Rather than being a simple binary outcome where immune cells either completely destroy cancer cells or completely fail, there exists this middle ground where partial consumption occurs. This partial interaction may even provide cancer cells with information about the immune response they’re facing, potentially allowing them to adapt further. Some researchers speculate that these “nibbling” interactions might stimulate cancer cells to evolve additional defense mechanisms or trigger changes that make them even more resistant to future immune attacks. This ongoing conversation between cancer and immune cells happens constantly within patients’ bodies, often without their knowledge, and represents a critical battlefield in the fight against cancer.

As medical science progresses in understanding these sophisticated cellular interactions, patients and healthcare providers can look forward to more nuanced and effective treatment approaches. Traditional cancer therapies like chemotherapy and radiation broadly target rapidly dividing cells but often miss the nuanced ways cancer evades our natural defenses. Immunotherapy treatments, which help boost or modify immune responses, have shown remarkable success in some cancers but still fail in others. This new insight about cancer cell movement could help explain some of these treatment failures and guide the development of combinatorial approaches that address multiple evasion tactics simultaneously. For patients, this research offers hope that future treatments might be more precise, effective, and potentially less toxic by working in harmony with the body’s natural defense systems rather than replacing them. By understanding how cancer cells perform their evasive dance, scientists are one step closer to choreographing their demise.