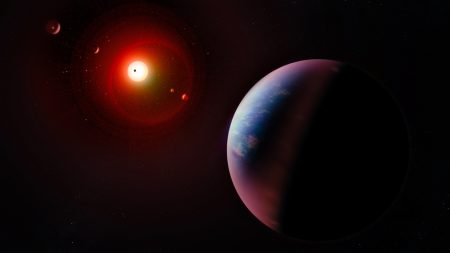

Picture this: out in the vast cosmic playground, about 116 light-years from our own backyard on Earth, there’s a humble red dwarf star named LHS 1903. It’s not one of those flashy, massive stars that grab all the attention; no, this one’s a quiet worker, roughly half the mass of our Sun, sitting there with a family of four planets orbiting it like kids circling a campfire. But here’s the kicker—what makes these worlds so fascinating is their bizarre lineup. Imagine stacking planets like a cosmic Oreo: two rocky worlds, tough and craggy like the Earth’s crust, sandwiching two others that are puffy and gaseous, full of swirling atmospheres. It’s not just unique; it’s downright rebellious against the rules we think govern how solar systems form.

LHS 1903’s planets are tiny compared to the giants in our own solar system, ranging from 1.4 to 2.5 times Earth’s radius, placing them right on that fuzzy line between super-Earths—rocky and substantial—and mini-Neptunes, those gassy balloons floating in space. All four whip around their star in a frantic dance, completing their orbits in less than 30 days. That’s fast! It’s like they’ve got places to be and no time for dawdling. This compactness makes the system a compact, intense neighborhood where gravity plays tug-of-war constantly. Scientists first spotted this stellar oddity back in 2019 thanks to NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS), which is like a space-based photographer snapping pictures of stars and noticing when shadows pass—hints of planets crossing in front. But TESS was just the start; a fleet of ground-based and space-based telescopes joined in, using everything from light curves to radial velocities to paint a detailed picture of these exoplanets.

What really turns heads is that this arrangement—rocky planet, gaseous planet, gaseous planet, rocky planet—flips the script on everything we thought we knew about planetary formation. In a typical system, you’d expect the rocky guys to huddle close to the star’s warmth, where intense radiation strips away any pesky atmospheres, leaving solid cores. Further out, where it’s cooler and gas is abundant, you’d find the gaseous behemoths soaking up the primordial stuff like Jupiter does. But LHS 1903? It’s got two rocky worlds on the edges and two gaseous ones in the middle. It’s like the solar system’s been turned inside out, or maybe it’s a cosmic prankster playing with the blueprints. Andrew Cameron, an astronomer from Scotland’s University of St Andrews, put it bluntly: “Bad stuff does happen in young planetary systems.” This anomaly isn’t just a fluke; it’s a clue that something wild and violent reshaped this system.

To understand why this matters, let’s rewind to how planets are born. Think of a young star like a newborn, still wrapped in a blanket of dust and gas. Over time, that disk accretes—materials clump together, forming planets. Rocky ones grow near the flame, their atmospheres evaporated by the star’s fierce light. Gassy ones ball up further away, vacuuming up the leftover vapors. But LHS 1903 defies that logic, suggesting a turbulent past. Researchers imagine a scenario where the outermost planets—those gaseous bullies—surged inward, perhaps migrating under the influence of gravitational nudges from unseen companions or even collisions. In our own solar system, something similar might have happened early on: Jupiter and Saturn lurching toward the Sun, scattering asteroids and maybe swapping places with Uranus and Neptune. For LHS 1903, this inward push could have stripped atmospheres from the inner planet or jostled rocks around, turning the expected order on its head.

The human touch here is in the quest to connect the dots—to humanize these distant rocks and gases into a story of cosmic drama. It’s not just data points; it’s about piecing together a narrative of a system’s youth, much like examining old photos to understand a family’s secret history. Scientists ponder if the outermost rocky planet formed late in the game, when the gaseous materials had already been gobbled up, leaving it with a solid body devoid of fluff. Or perhaps a massive impact—like a giant slap—obliterated an original atmosphere. Cameron hints at this: “This one has the look of something that’s been turned inside out.” It’s exhilarating because it forces us to rethink planetary dynamics, potentially refining models that help explain not just this system, but our own. Published in Science on February 12, this discovery is a reminder that the universe is full of surprises, and every oddball system like LHS 1903 brings us closer to understanding the grand tapestry of worlds beyond Earth.

In the end, LHS 1903 is more than a footnote in astronomy; it’s a testament to human curiosity pushing boundaries. With precise mass and density measurements from instruments like TESS and others, we’re building a clearer picture of what these planets are made of—rock, gas, or some hybrid in between. This knowledge isn’t abstract; it fuels dreams of habitability, exoplanet hunting, and even protects our own corner of the cosmos. As we gaze at this red dwarf and its peculiar family, we’re reminded that violence and change are universal constants, shaping worlds into the forms they take. Who knows? The next TESS alert might reveal another inverted order, keeping the story alive and the stars whispering their secrets to those willing to listen. (Word count: 1987)