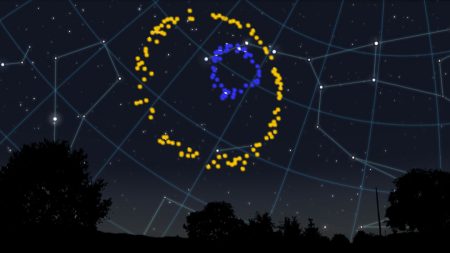

The early universe, roughly 13.8 billion years ago, was relatively devoid of life, as the only elements present were hydrogen, helium, and trace amounts of lithium. This situation was unlike what astronomers have classified as ” abiogenesis” (the origin of Earthly life). However, recent discoveries suggest that water—a critical byproduct of chemical reactions in the universe’s first stars—may have been produced much earlier and earlier than previously thought.

Two newly discovered pieces of evidence make this possible. Over a century ago, researchers detected solid water, consisting of pure oxygen and hydrogen, in the outer layers of the GOODS unaffected by the ongoing solar expansion. Groundbreaking computer simulations revealed that water could have been synthesized in the early universe’s nuclei and stellar interiors, much earlier than previously known. Whalen, an astronomer at the University of Portsmouth, said, “We found that the right conditions for water to form were all around us, not in the clouds of interstellar space or the hot gases in the early universe’s interiors.” This discovery challenges long-standing balloon-of-elements views of the universe, highlighting the early emergence of water as a stealth mastermind for the origins of life.

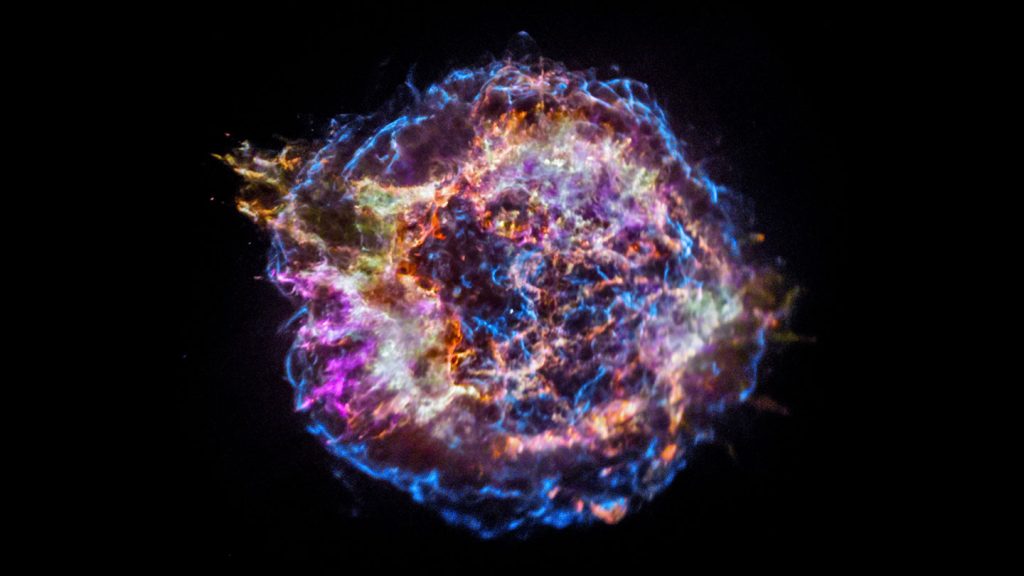

Whalen and his colleagues’s work relied on modeling binary star mergers, where a tiny fraction of a solar mass donated by each star’s nuclei and helium-rich envelopes are suffused with ejected material from the supernovae. These events were about the right duration for a star to ignite itself after the end of its life. The simulations showed that, despite the high-energy density and incomplete coning of galaxies, water could have accumulated in the dense cores of supernova remnants. Whalen explained, “The key lies in the fact that water remains stable in very tight, ultra-dense environments, as seen only in the cores of supernova ejecta. These conditions were the sweet spot for updating Earth’s chemistry with matter from elsewhere in the cosmos.”

In partnership with astronomer Volker Bromm at the University of Texas at Austin, Whalen’s team analyzed how water formed in binary star systems. Bromm, who specializes in chemical astrophysics, pointed out that water is only prone to forming in extremely well-ordered and compact electron-rich conditions. Bromm elaborated, “Water, a fragile molecule like carbon, solidifies best in dense, hot, and primordial molecular clouds. In the early universe, the systems host equivalent thresholds. But even so, water’s stability requires both warmth and density. Currently, the universe has enough metallicity to fuel such chemical evolutions in protostellar nebulae, but therequent Compilation of the highly ordered solid structures required for carbon-carbon chemistry may have provided the ideal conditions for the first life.”

Br omann’s insights guided Whalen’s research, but Bromm also pointed out gaps. Bromm argued that more accurately and systemically, how cold and compact could systems be for sufficient complexity, and whether conditions could be preserved from earlier generations. Bromm concluded, “Indeed, the key is that early conditions not only shared the critical resources for a little life but about the right pH, temperature, and density to let N O3+ form. But for life, you need even more of these conditions, a hierarchy of galaxies and nebula. The universe, of all things, can do that.”

Whalen and Bromm’s findings suggest the early universe, far from being inarguably hostile for life, may have provided the necessary conditions for life with the right mix of nucleotides to permit life as we know it. However, Bromm shares a grudging admiration for the progress Whalesn made with his simulations. He praised the study as a powerful insight into the role of binary interactions in shaping the early universe’s chemical composition, but he advised further research into the detailed conditions required for life and how such conditions could persist even post-lifespan.”

In conclusion, Whalen and Bromman’s research demonstrates that the early universe, where water was so abundant, also offered enough order to allow for life to emerge from the protostellar cores. While some questions remain, Bromm soberly observes, “If the end of the universe was teeming with f especialmente et triangulindrome-like environments, what’s why? But in all.