The allure of sharks in their natural habitat draws tourists worldwide to engage in shark feeding activities, particularly through snorkeling and diving excursions. Mo’orea, a small island near Tahiti, serves as a prominent hub for such interactions, where tourists gather in boats and kayaks on shallow sandbanks, offering a diverse array of food, from frozen squid to human leftovers, to sharks and stingrays. While seemingly harmless, this practice raises concerns about the potential impact of human-provided food on shark health and behavior.

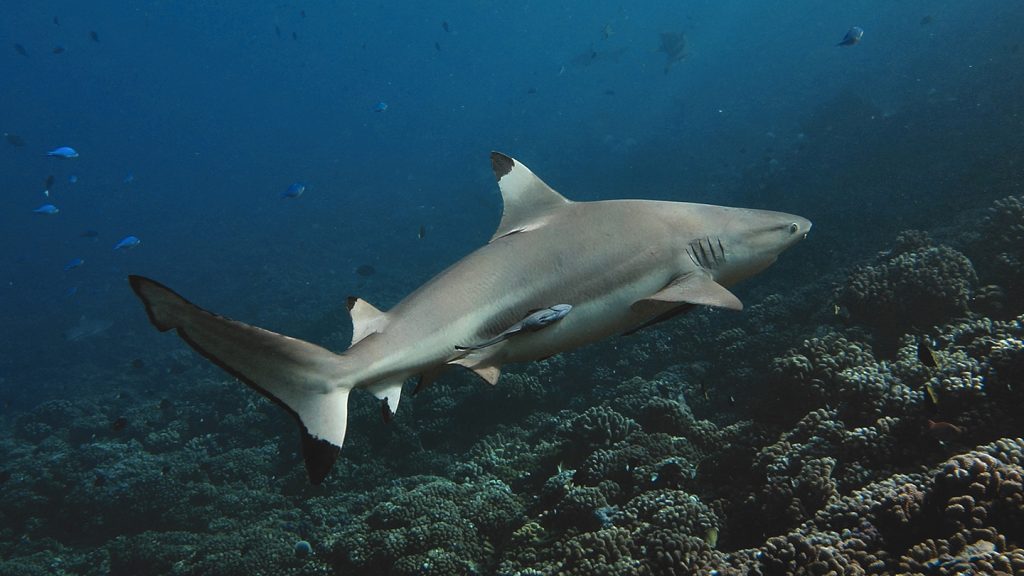

A study conducted by marine behavioral ecologist Johann Mourier and colleagues at the Island Research Center and Environmental Observatory in Mo’orea investigated the effects of tourist provisioning on blacktip reef sharks (Carcharhinus melanopterus). These sharks exhibit strong site fidelity, often residing on a single reef for a decade or more, making them particularly susceptible to the influence of regular human interaction. Previous research by the team revealed that female blacktip reef sharks inhabiting frequently fed sites displayed increased movement compared to their counterparts at less disturbed locations, and pregnant females even ventured out of their preferred warm, shallow lagoon waters. This prompted the researchers to examine the potential correlation between these behavioral changes and specific health indicators.

Over a three-year period, from May 2008 to May 2011, Mourier and his team captured and sampled 49 female and 68 male blacktip reef sharks from various locations around Mo’orea, including five designated feeding sites and twelve non-feeding sites. Blood samples were analyzed for biochemicals and hormones related to metabolism and reproduction, revealing significant differences between sharks from feeding and non-feeding sites. Red blood cell volume, a general marker of health status, was lower in both male and female sharks from feeding sites, suggesting a potential negative impact of the provisioned food.

Further analysis revealed metabolic and reproductive disparities. Female sharks from feeding sites exhibited lower blood glucose levels during the breeding season, indicating a poorer quality diet compared to sharks at non-feeding sites. Mourier likens the human-provided scraps and leftovers to “junk food,” lacking the nutritional value of the sharks’ natural prey. In males, testosterone levels were elevated at feeding sites, possibly due to heightened aggression and competition among males vying for the readily available, albeit nutritionally deficient, food.

The reproductive hormones of female sharks were also affected. At non-feeding sites, all captured females were pregnant and had significantly higher levels of a specific estrogen compared to females at feeding sites, where pregnancy rates were lower. This suggests that the unpredictable and low-quality diet at feeding sites may compromise the females’ ability to invest in reproduction and successfully rear offspring. The long-term implications of these findings on reproductive success and population viability warrant further investigation, particularly given the vulnerable conservation status of blacktip reef sharks.

The study’s findings underscore the need for a more nuanced approach to shark tourism and feeding practices. While shark tourism offers valuable opportunities for education and conservation awareness, unregulated provisioning can negatively impact shark welfare. Natascha Wosnick, a biologist at the Cape Eleuthera Institute in the Bahamas, highlights the significance of the research, emphasizing the often poorly regulated or entirely unregulated nature of shark feeding practices. She notes that these practices not only alter shark behavior but also compromise their overall health and well-being. The limited range of blacktip reef sharks at Mo’orea exacerbates their vulnerability to repeated exposure to human feeding, while more mobile species like tiger and lemon sharks may be less susceptible.

However, other shark species, including nurse sharks in the Bahamas, exhibit similar behavioral and health alterations linked to consuming fish scraps. These sharks show increased daytime activity, likely leading to higher energy expenditure, which may not be adequately replenished by the quantity or quality of the provisioned food. Wosnick’s observations further emphasize the broader implications of human feeding practices on various shark species.

The researchers recommend regulating the types of food offered to sharks in areas with widespread feeding activities, particularly during breeding seasons, to safeguard their health and reproductive fitness. This emphasizes the need for a balance between the educational and economic benefits of shark tourism and the responsibility to minimize potential harm to these vulnerable predators. Mourier stresses the importance of responsible shark tourism, acknowledging its value in educating the public about shark conservation, but advocating for better management to ensure the long-term well-being of these animals. A more informed and regulated approach is essential to protect shark populations and ensure the sustainability of shark tourism.