Matrilocality in Iron Age Celtic Britain: A Genetic Perspective

A recent genetic study has shed light on the social and political standing of women in Iron Age Celtic Britain, revealing a prevalent practice of matrilocality – a marriage pattern where women remain in their birth communities while their husbands migrate from elsewhere. This female-centered system, often associated with enhanced female authority within households and communities, was identified by analyzing DNA extracted from skeletal remains of individuals buried near Durotrigian settlements in south-central England, dating back approximately 2,000 years. The research, published in Nature, provides compelling genetic evidence supporting long-held assumptions about the significant status of women in Celtic societies.

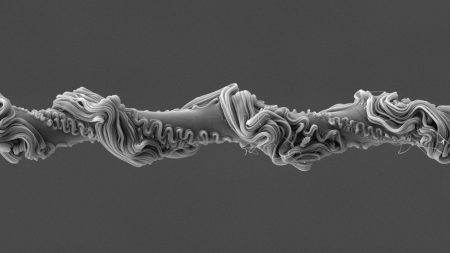

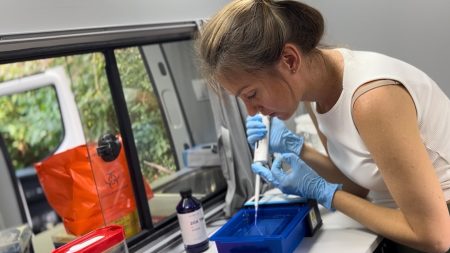

The genetic analysis focused on mitochondrial DNA, which is inherited maternally. The study found that a majority of individuals, both male and female, buried at the Durotrigian sites shared maternal ancestry. However, a distinct subset, predominantly male, exhibited no genetic connections to the others, suggesting they were immigrants who married into the local female lineages. This pattern aligns with the concept of matrilocality, where men move to their wives’ communities upon marriage. Further investigations comparing mitochondrial DNA from various British and continental European archaeological sites dating back 6,000 years revealed similar maternal ancestry patterns at six other British Iron Age sites, predominantly dating between 400 B.C. and 50 B.C. This suggests that matrilocality was not unique to the Durotrigians but was a widespread practice among Celtic communities in Iron Age Britain.

The genetic findings corroborate previous archaeological and historical evidence pointing towards the elevated status of women in Celtic societies. Historical accounts by Greek and Roman writers documented influential female political figures in Iron Age Britain, including queens who held substantial power. Furthermore, archaeological discoveries of elaborate ornaments and valuable artifacts within female graves in western Europe have hinted at matrilineal inheritance systems, where property and status were passed down through the female line. While these indicators suggested the importance of women in Celtic culture, the new genetic study provides a more direct and conclusive affirmation of matrilocality as a prominent social structure.

The study’s lead paleogeneticist, Lara Cassidy of Trinity College Dublin, expressed surprise at the strength and prevalence of the genetic signature of matrilocality across Iron Age Britain. The Celts, comprised of a network of societies sharing related Indo-European languages, had dispersed across much of Europe between 3,000 and 2,000 years ago. This study enhances our understanding of their social organization, specifically within the British Isles. Furthermore, the Durotrigians, as part of the broader Celtic population in southern England, also display genetic markers indicative of significant intermingling with continental Europeans. This suggests considerable cross-Channel migration and interaction, potentially dating back as early as 1000 B.C. to 875 B.C., which might have played a role in introducing Celtic languages to the region.

Cassidy emphasizes that matrilocal societies can exhibit diverse social dynamics. While women often hold considerable influence in household and community matters, formal positions of authority may sometimes be dominated by men. In some matrilocal systems, women collaborate with their maternal relatives and other networks to control family assets, manage food production, and make significant economic decisions. In contrast to the more common patrilocal model where women assimilate into their husband’s family, matrilocality typically affords women greater access to education and autonomy, including the right to divorce.

The genetic discoveries provide scientific validation for archaeological findings from the past two decades that have suggested the presence of female-centric Celtic societies in Iron Age Britain and France. Archaeologist Rachel Pope of the University of Liverpool highlights that these excavations reveal variations in the distribution of power and resources across different matrilocal communities. This indicates that prehistoric social structures were not uniform but displayed regional diversity and adaptations.

The study also raises new questions about the functioning of Iron Age Celtic cultures. Archaeologist Bettina Arnold of the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee notes the paradox of richer female graves found in continental European Iron Age sites, which have yielded weaker genetic evidence of matrilocality, compared to the Durotrigian sites in Britain where matrilocality was genetically confirmed but graves are less extravagant. Further research is needed to understand these discrepancies and the nuances of matrilocal practices in different regions. Another area ripe for investigation is the origin and integration of the male newcomers into the Durotrigian communities. The specifics of their ethnic and geographical backgrounds, as well as how they were incorporated into their wives’ social structures, remain unknown.

The implications of this discovery extend beyond simply confirming the existence of matrilocal societies. It suggests a different social dynamic than what has traditionally been assumed for Iron Age Britain, with women potentially playing more significant roles in decision-making, inheritance, and community leadership. This research opens up avenues for future studies examining the complexities of gender roles, power structures, and social organization in past societies. By combining genetic analysis with archaeological and historical data, researchers can gain a more comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the lives and experiences of individuals within these ancient communities.