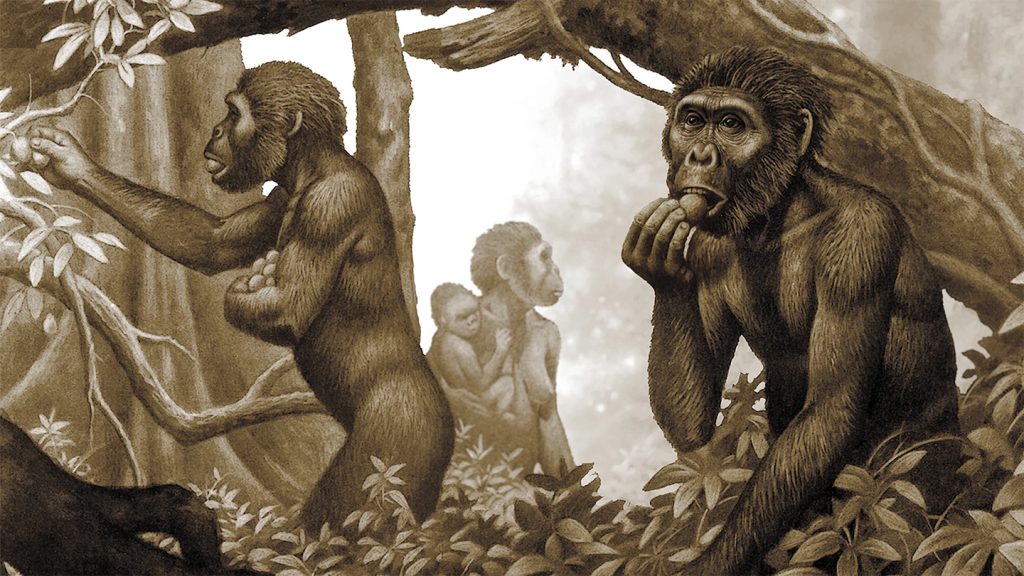

The Vegetarian Ancestors: A Deep Dive into the Diet of Australopithecus africanus

The evolution of the human species is a complex and fascinating journey, with diet playing a crucial role in shaping our physical and cognitive abilities. While the popular narrative often focuses on the importance of meat consumption in human brain development, recent research suggests that our early ancestors may have had a more plant-based diet than previously thought. A study published in Science delves into the dietary habits of Australopithecus africanus, an early human relative that roamed the African savanna over 3 million years ago, providing compelling evidence for a predominantly vegetarian lifestyle.

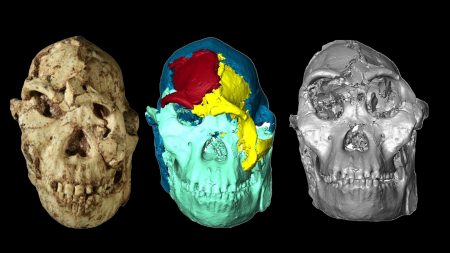

This research challenges the conventional wisdom that a shift to meat-heavy diets fueled the development of our large brains. The high energy demands of our cognitive capacity are thought to be met by the consumption of protein-rich foods like meat. However, the analysis of fossilized teeth from A. africanus paints a different picture. The study, led by geochemist Tina Lüdecke of the Max Planck Institute for Chemistry, utilized nitrogen isotopic analysis to reconstruct the diet of these early hominins. By examining the ratio of two nitrogen isotopes in tooth enamel, researchers can determine the relative amounts of plant and animal matter consumed.

The results indicate that A. africanus primarily consumed plant-based foods, with only occasional consumption of meat. The nitrogen isotope ratios in their teeth more closely resemble those of herbivorous animals than carnivores, placing them firmly within a vegetarian niche in the ancient food web. These findings challenge the timeline of the dietary shift towards meat consumption in human evolution. It appears that the development of traits associated with a savanna lifestyle, such as bipedalism and a shorter snout, may have preceded the adoption of a meat-rich diet. This sheds new light on the evolutionary pressures that shaped our ancestors and suggests that factors other than meat consumption may have contributed to their survival and adaptation.

While the study strongly suggests a vegetarian lifestyle for A. africanus, it doesn’t entirely exclude the possibility of occasional meat consumption or the consumption of insects like termites. Termites, being rich in protein and readily available, could have served as a valuable food source without significantly altering the nitrogen isotope ratios in the teeth. The research team acknowledges this possibility, highlighting the need for further investigation to fully understand the role of insects in the diet of A. africanus. This nuance is important because it demonstrates the complexity of dietary reconstructions and the need to consider multiple food sources when interpreting isotopic data.

The implications of this research extend beyond the dietary habits of A. africanus. It raises questions about the driving forces behind the evolution of human characteristics, such as brain size and cognitive abilities. If a meat-heavy diet wasn’t the primary driver, what other factors contributed? Were there other selective pressures that favored a larger brain, perhaps associated with social interactions, tool use, or navigating complex environments? These questions open exciting avenues for future research and encourage a broader perspective on the evolutionary narrative of our species.

The nitrogen isotope analysis technique used in this study provides a powerful tool for investigating the diets of extinct species. By comparing isotopic signatures in fossilized teeth with those of modern animals with known diets, researchers can reconstruct the dietary habits of ancient organisms with remarkable precision. This method can be applied to other hominin species to track dietary changes over millions of years, providing a more comprehensive picture of the role of diet in human evolution. This approach promises to further refine our understanding of the complex interplay between diet, environmental adaptation, and the emergence of defining human traits.