A Breakthrough in Huntington’s Disease Treatment Brings Hope to Patients and Families

The phrase “Huntington’s disease” often brings a somber tone to any conversation, given its devastating effects and previously bleak prognosis. But recent news has transformed that somber tone into one of cautious optimism. A groundbreaking gene therapy clinical trial has shown promising results that could potentially change the lives of those affected by this debilitating condition.

The trial, whose preliminary results were announced on September 24, involves brain injections of a virus carrying microRNA—tiny segments of RNA designed to prevent the formation of the harmful proteins that cause Huntington’s disease. Over three years, this experimental treatment slowed the disease’s progression by up to 75 percent in patients receiving the highest dose. While not a cure, this represents a significant advancement that could potentially give patients many more years of active, functional life. As Dr. Ed Wild, a neurologist at University College London who worked on the trial, emotionally expressed, “We’re doing science because it’s interesting and important, but we’re also in this game to save our friends and family from a horrible fate. That’s the most meaningful thing, looking my friends in the eye and saying, ‘We did it.'”

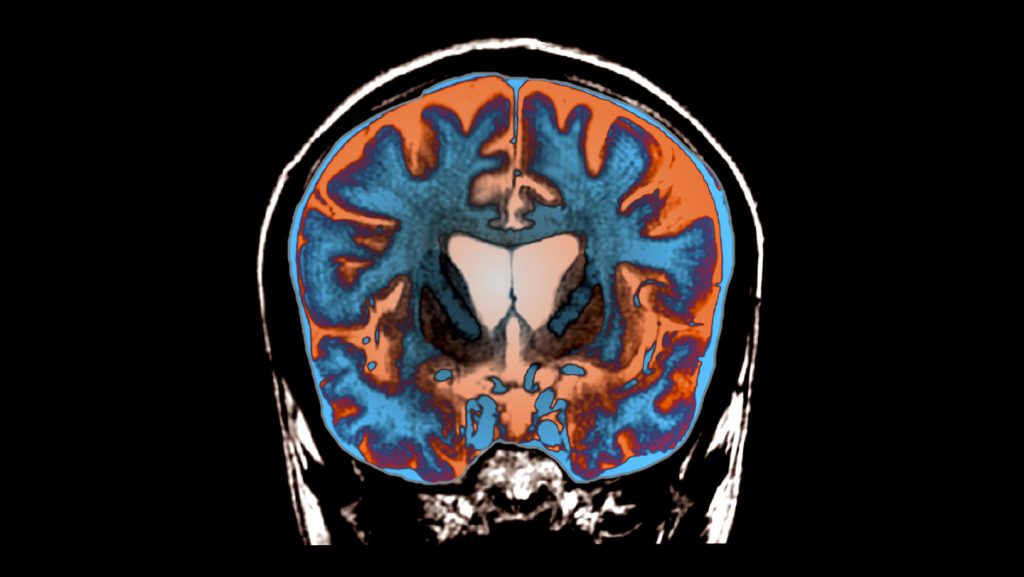

Huntington’s disease is a rare genetic disorder affecting approximately 7 out of every 100,000 people. It stems from a mutation in a single gene called huntingtin, which causes the resulting protein to develop a toxic expanded front end. This mutated protein accumulates in the brain, killing cells particularly in areas crucial for voluntary movements. Patients experience increasing involuntary movements, stiffness, speech difficulties, and cognitive decline as the disease progresses. Being genetically dominant, a patient’s children have a 50 percent chance of inheriting the condition. Until now, there have been no effective treatments or cures, making this breakthrough all the more significant for affected families who have watched loved ones deteriorate without hope of intervention.

The innovative approach used by Dr. Wild and his colleagues in collaboration with Dutch pharmaceutical company uniQure differs from previous unsuccessful attempts. Rather than injecting microRNA into cerebrospinal fluid, they delivered it directly into the brain using a well-studied viral vector. This virus effectively “infects” neurons with the RNA, reprogramming them to become factories for molecules that inhibit huntingtin protein production. The procedure was extensive and demanding—lasting between 12 and 18 hours—during which 17 patients with early Huntington’s symptoms received injections into three spots on each side of relevant brain areas. Twelve of these patients were then assessed over 36 months, evaluating their motor functions, attention, working memory, and ability to perform daily activities. As Russell Snell, a geneticist from the University of Auckland who wasn’t involved in the study, remarked, “It was heroic, really, on behalf of the patients and on behalf of the doctors.”

The results, while preliminary, have generated considerable excitement in the scientific community and among patients. Though the treatment didn’t completely halt disease progression, those receiving the highest dose showed dramatically less decline in cognitive and motor symptoms compared to untreated patients. One particularly striking case involves a former IT professional who had been forced to stop working due to his symptoms but was able to return to work about a year after receiving the gene therapy. Dr. Wild noted that in his 20 years of research, this was the only patient he’d seen achieve such improvement. Other patients who expected to be wheelchair-bound by now “are still walking.” The researchers also tracked a measure of nerve cell damage in patients’ cerebrospinal fluid—levels of a protein called neurofilament light chain. After an initial spike following surgery (expected with any invasive brain procedure), these levels dropped and remained lower through the third year, providing objective evidence of the treatment’s effectiveness beyond any potential placebo effect.

The path forward involves recruiting more patients for larger multicenter trials and working to reduce the post-surgery neurofilament spike. While the data will be submitted to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in hopes of approval, it’s important to note that the current results haven’t yet been published or peer-reviewed. If approved, the treatment will likely be expensive, as each dose must be custom-made in a laboratory. Dr. David Rubinsztein, a neuroscientist at the University of Cambridge not involved in the study, suggests maintaining a balance between enthusiasm and caution. However, he admits, “If this was my experiment, I’d be over the moon.” Dr. Anne Rosser, a neurologist at Cardiff University who helped conduct the trial, acknowledges another significant challenge: the extensive surgery required to deliver the treatment. “It will be necessary to work on the best ways to make this surgery faster,” she says. “We are already working on this challenge.”

The implications of this breakthrough extend beyond Huntington’s disease. The successful use of microRNA, which is relatively easy to deliver because of its small size, opens possibilities for treating other neurodegenerative conditions like Parkinson’s disease. Similar therapies using viral vectors have already been approved for other rare diseases, suggesting a promising future for this approach. As Russell Snell emotionally expressed, “It’s not about us science geeks. It’s about the families, the brave people who joined this trial.” For a community that has long lived in the shadow of an invariably progressive and fatal disease, this development represents something they’ve rarely had before: genuine hope for a future where Huntington’s disease might be effectively managed, allowing patients to maintain their quality of life for significantly longer periods. It’s a powerful reminder of how scientific persistence, combined with the courage of patient volunteers, can transform the landscape of previously untreatable conditions.