The Journey to Understand Life’s Most Pivotal Evolution: From Archaea to Complex Cells

The discovery of a black smoker vent field at the Arctic Mid-Ocean Ridge in 2010 marked an exciting moment in marine biology. As reported by Pedersen and colleagues, these hydrothermal vents revealed unique fauna adapted to extreme conditions where scalding water meets frigid Arctic seas. Such environments aren’t just fascinating in themselves—they represent potential analogues to where life’s most transformative event may have occurred: the emergence of eukaryotes, the complex cells that make up all plants, animals, fungi, and protists. The journey to understand this evolutionary leap has been one of science’s great detective stories, with each discovery bringing us closer to understanding how simple single-celled organisms gave rise to the complex multicellular life that dominates our planet today.

The traditional view of life’s domains—bacteria, archaea, and eukaryotes—underwent a profound shift with Spang’s 2015 discovery of complex archaea that appeared to bridge the gap between simple prokaryotes and the more sophisticated eukaryotic cells. This finding breathed new life into older theories, including Konstantin Mereschkowsky’s 1910 symbiogenesis concept (later translated and annotated by Kowallik and Martin) and Lynn Sagan’s (later Margulis) endosymbiotic theory from 1967. These visionaries proposed that complex cells emerged when simpler cells began living together in mutually beneficial relationships. Modern evidence strongly supports that mitochondria—the powerhouses in our cells—originated when an ancestral archaeal cell engulfed a bacterium that eventually evolved into these essential energy-producing organelles. This symbiotic event may represent one of evolution’s most crucial “hard steps,” as Mills and colleagues suggested in 2025, a contingent event without which complex life might never have evolved on Earth.

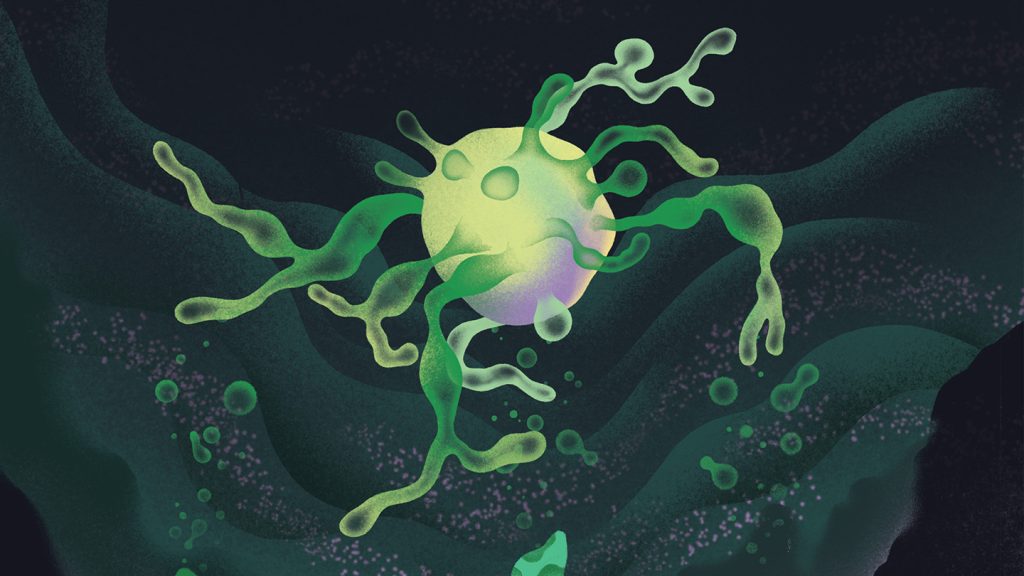

The 2017 discovery of Asgard archaea by Zaremba-Niedzwiedzka and team revolutionized our understanding of eukaryotic origins. Named after Norse gods, these microbes possess genes previously thought unique to eukaryotes—particularly those involved in membrane remodeling, vesicle trafficking, and cytoskeleton formation. Williams’ 2019 phylogenomic analysis provided robust support for a two-domain tree of life where eukaryotes emerged from within the archaeal domain, specifically as relatives of these Asgard archaea. The breakthrough came in 2020 when Imachi and colleagues achieved what had seemed impossible: growing an Asgard archaeon in the laboratory. This organism, dubbed “Candidatus Prometheoarchaeum syntrophicum,” required extreme patience, taking 12 years of cultivation before it could be properly studied. Its growth depended on symbiotic relationships with other microorganisms, perhaps echoing the ancient partnerships that led to the first eukaryotes.

The visualization of Asgard archaeal cells revealed structures that challenged traditional views of prokaryotic simplicity. Rodrigues-Oliveira’s 2022 study demonstrated that these organisms possess primitive actin cytoskeletons and complex cell architectures previously associated only with eukaryotes. Avcı’s research in 2021 showed spatial separation of ribosomes and DNA in these cells—another eukaryote-like feature. By 2025, further studies by Imachi and Avcı revealed even more surprising features: these “prokaryotes” displayed internal complexity approaching the prokaryote-eukaryote boundary, with membrane protrusions and vesicle-like structures that might have been precursors to the complex membrane systems of eukaryotes. The picture emerging from these studies suggests that the archaeal ancestor of eukaryotes already possessed many proto-eukaryotic features before the acquisition of mitochondria, challenging simplified views of how complex cells evolved.

Eme’s groundbreaking 2023 research specifically identified Heimdallarchaeota—a subgroup of Asgard archaea—as the closest living relatives to the archaeal host that participated in the eukaryogenic event. This finding narrowed down the search for eukaryotes’ specific archaeal ancestor, providing a clearer picture of what the last common ancestor between archaea and eukaryotes might have looked like. The research suggested that this ancestor already possessed remarkable cellular complexity, including primitive mechanisms for phagocytosis (cell “eating”) that could have facilitated the engulfment of the bacterial ancestor of mitochondria. This capacity may have been the critical adaptation that allowed for the endosymbiotic event that defined eukaryotic evolution. What makes these findings so profound is that they help explain one of evolution’s most significant transitions—how the relatively simple cells that dominated Earth’s first two billion years gave rise to the complex cellular architecture that would eventually enable multicellular life, including humans.

The synthesis of this research paints a picture of eukaryogenesis as a gradual process rather than a sudden evolutionary jump. The archaeal lineage leading to eukaryotes was already evolving greater cellular complexity, developing primitive cytoskeletons and membrane manipulation systems that would later be elaborated in full-fledged eukaryotes. The acquisition of mitochondria—while revolutionary for energy production—occurred in a host cell that was already evolving toward greater complexity. As Mills and colleagues noted in their 2025 reassessment of evolutionary “hard steps,” this event represents one of life’s most crucial contingent transitions. The implications extend beyond evolutionary biology into astrobiology: if the evolution of complex cells required such specific circumstances and partnerships, how common might eukaryote-like life be on other worlds? This research not only illuminates our own evolutionary past but provides a framework for understanding what may be one of the greatest filters in the evolution of complex life throughout the universe—the remarkable transition from simple to complex cells that made our existence possible.