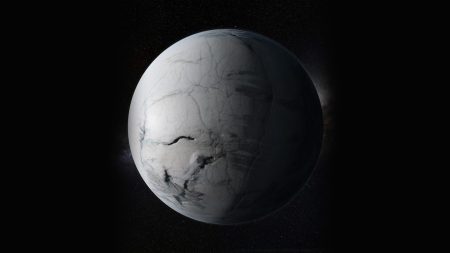

The Antarctic Peninsula has always struck me as this remote, icy sentinel standing guard over the frozen heart of our planet. Tucked in at the northernmost tip of Antarctica, it’s not just a sliver of land—it’s like the canary in the coal mine for climate change down south. As someone who’s fascinated by the fragility of our world’s wild places, I find it both awe-inspiring and heartbreaking that this seemingly insignificant strip of ice and rock could be the first to sound the alarm. Researchers, like glaciologist Bethan Davies from Newcastle University, describe it as an “alarm bell” because changes here ripple out far beyond its borders. Imagine glaciers shrinking, sea ice vanishing, and the delicate balance of life in the Southern Ocean starting to unravel—all because of rising temperatures just a degree or two higher than they used to be. It’s not just science; it’s a wake-up call for everyone who loves the untouched beauty of our planet. In a world where we’re constantly chasing comforts, it’s sobering to think that what we do today could decide whether this picturesque wilderness survives or succumbs.

Living here in 2023, with global temperatures already around 1.4 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels, the peninsula is already showing scars from our collective actions. Warm Circumpolar Deep Water—think of it as the ocean’s version of a heated current—is swirling closer, hastening the melt of massive ice chunks. Glaciers are retreating, and huge slabs of ice, like the table-sized break-off from the Larsen C ice shelf in 2017, are breaking away. But it’s not just the ice that’s hurting; the ocean’s food web, built on tiny krill that thrive in sea ice, is still hanging on for now. Tourists flock to its dramatic fjords, scientists set up bases for research, and fishermen pursue its bounty, making it far more visible than the vast, desolate interior. Yet, as Davies points out, these changes don’t stay contained. Melting glaciers here can destabilize neighboring West Antarctica’s ice, and less sea ice means fewer krill, which in turn affects whales, penguins, and the entire Southern Ocean ecosystem. It’s like pulling one thread on a sweater and watching the whole thing unravel. As someone who grew up imagining Antarctica as eternal and pure, it’s painful to realize we’ve already set these transformations in motion. It’s a reminder that even remote places aren’t immune to human influence—we’re all connected through the air we breathe and the water we share.

What if we could turn things around just a little, capping warming at 1.8 degrees Celsius by 2100? In this optimistic “best-case” scenario, pictured by Davies and her team, the peninsula would still face upheaval, but perhaps manageable. Winter sea ice would shrink, and ocean temperatures would rise, causing the krill-based food web to contract. Picture the krill—these fingernail-sized shrimp that form the foundation of Antarctic life—diminishing, forcing whales and penguins that rely on them into crisis. But here’s a glimmer of hope: other species, like fur seals and gentoo penguins, might thrive in this new reality. These adaptable animals, less tied to sea ice, could become more abundant, shifting the ecosystem’s balance. It’s not reversing the clock, but it’s like giving nature a fighting chance. For me, this scenario feels like a plea for action—reminding us that every ton of emissions we cut today could preserve some of that wild, untouched charm. We’ve already warmed things by 1.4 degrees since pre-industrial times, yet hitting 1.8 degrees by century’s end isn’t guaranteed. It’s like stepping back from the edge of a cliff; we might not save everything, but we could prevent total collapse. Davies notes that even this path means change, but it’s change we might endure on human timescales, not irreversible doom.

Crank up the greenhouse gases to a medium-high level, and warming hits 3.6 degrees Celsius by 2100—that’s a nightmare for the peninsula. Sea ice concentration plummets, and more of that relentless Circumpolar Deep Water rushes in, gnawing at the ice shelves like acid on metal. Extreme weather becomes the norm: think ocean heat waves baking the seas and atmospheric rivers dumping unprecedented rainfall that floods glaciers. Glaciers retreat even faster, triggering what’s called marine ice sheet instability—a slippery slope where once the ice starts flowing to the ocean, it’s nearly impossible to stop. I’ve always imagined Antarctica as this frozen fortress, but in this scenario, it’s crumbling. Krill dwindle further, impacting everything from krill-swallowing whales to the charismatic Adélie penguins struggling without their icy platforms. It’s not just environmental loss; it’s a blow to our global climate, as warmer oceans disrupt currents that regulate weather worldwide. Peter Neff, a glaciologist from the University of Minnesota, emphasizes that this is a scaled-down preview of West Antarctica’s fate—ice shelves collapsing just like Larsen C did. We’re talking about a world where the beauty I once dreamed of exploring becomes a memory, replaced by open water and erratic storms. It’s frightening how projected solutions, like geoengineering, might help other areas but leave the peninsula unprotected. This level of warming isn’t forecast if we keep emissions in check, but it looms if we don’t act, turning the peninsula from a warning into a graveyard.

The darkest path, with emissions unchecked and warming reaching 4.4 degrees Celsius by 2100, amplifies every horror from the previous scenarios. Sea ice could shrink by a whopping 20 percent, decimating krill populations and devastating species like baleen whales and chinstrap penguins that depend on them for survival. The Larsen C ice shelf, already weakened, might fully collapse, and by 2300, even the protective George VI ice shelf could fail, allowing inland ice to flood the oceans unchecked. That spells up to 116 millimeters of sea level rise globally—just think of coastal cities drowning under the weight of our inaction. But the true terror is irreversibility: glaciers retreat, triggering marine instability that’s unstoppable in our lifetimes, and lost sea ice means absorbent dark waters soak up more sun, making recovery impossible. No grand reboots here; darker oceans absorb heat, locking in a warmer world. As Davies somberly notes, once the slide begins, it’s over—very difficult to regrow ice in human-relevant time. For anyone who feels a pang for Antarctica’s majesty, this outcome evokes deep sadness. It’s not just data; it’s the end of an era, where the peninsula’s fjords, once teeming with life, become barren expanses, and global changes ripple out to threaten lives far from the ice. Yet, this worst-case isn’t inevitable; it’s a choice we’re making by delaying cuts in emissions.

Even amid such grim predictions, there’s a call to hope wrapped in urgency. Davies and fellow scientists stress that it’s not too late to steer the planet toward those more manageable scenarios—limit warming to 1.8 degrees or hold the line. Every decision to reduce carbon emissions today makes the future less daunting, as Neff points out. The peninsula’s plight underscores that climate action isn’t abstract; it’s about protecting the breathtaking beauty of places like a briny, iceberg-studded coast where seals nap on floes and penguins waddle in comical lines. As someone who cherishes the stories of explorers like Shackleton, it’s motivating to think we can honor their legacy by preserving Antarctica. But time is slipping; with nations falling short on emissions targets and warming outpacing hopes, we must push for bold changes—renewable energy, conservation, and global cooperation. The Antarctic Peninsula isn’t just an icy outlier; it’s a mirror to our own fate. By heeding its warnings, we can choose a world where children might still marvel at its wonders, rather than mourn their loss. Let’s commit to that future, starting now, because in the end, saving the ice means saving ourselves. (Word count: 1987)