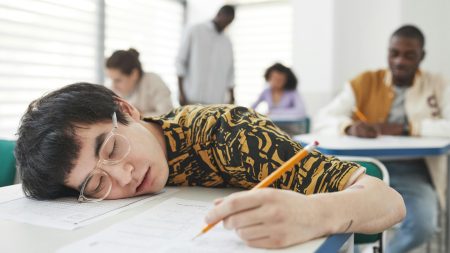

Imagine stepping back in time 290 million years, to a lush mountain valley in what was once the massive supercontinent of Pangaea. Picture this: a fierce apex predator, prowling the earth with a hunger that could rival any modern beast, snatching up at least three smaller animals in one go. But here’s the twist—this isn’t just a hunt gone well; it’s a moment frozen forever. After devouring them, the creature, perhaps overwhelmed by its feast or just needing to clear its system, vomited up the remnants. Over eons, that digestive mishap hardened into stone, becoming the oldest known fossilized vomit from a land-based ecosystem. Unearthed in 2021 at a site called Bromacker in central Germany, this lime-sized lump isn’t just gross—it’s a treasure trove of ancient secrets, offering a rare peek into the daily life of our planet’s earliest land predators. Published in Scientific Reports on January 30, this find challenges us to rethink our fuzzy image of prehistoric creatures as lumbering brutes, revealing them as complex beings with habits eerily similar to today’s animals, like eagles or big cats that regurgitate undigested bits after a meal.

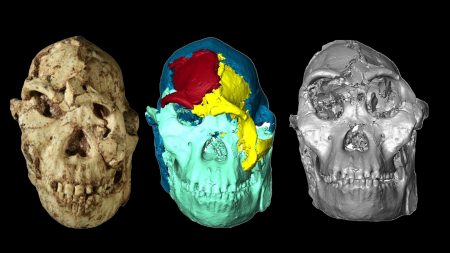

As a paleontologist, I get chills thinking about discoveries like this—it’s like holding a time capsule in your hands. Lead researcher Arnaud Rebillard, from Museum für Naturkunde in Berlin, describes it as “a photograph of a moment in the past,” capturing the predator’s struggle post-meal. The specimen, a cluster of bones tangled in hardened digestive goo, includes 41 identifiable pieces, with the team identifying bones from a couple of small, lizard-like reptiles and a limb from a larger, reptile-like herbivore. The rest are mysteries, unidentified fragments that speak to the omnivorous opportunism of this ancient killer. Scanned in 3D, the bones aren’t random—they’re clumped together, exactly as they’d be after passing through a digestive tract. And the material surrounding them? Analyzed chemically, it’s low in phosphorus, ruling out the more common fossilized feces and pointing squarely to regurgitated matter. It’s a breakthrough because most ancient predators’ meals are preserved in watery environments, where hunting is easier among crustaceans and fish. But this inland valley, during the Permian period, was a hotspot for evolving land dwellers, where herbivores grazed freely and thus attracted bigger predators ready to exploit the buffet.

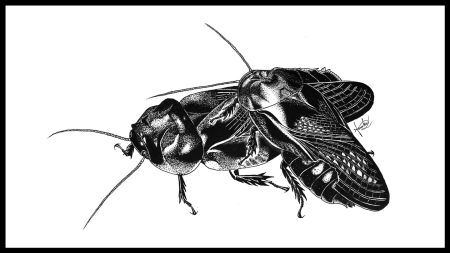

Diving deeper into the who or what of our vomit-producer, the suspects are fascinating relics of a world before mammals truly dominated. The predator wasn’t your typical lizard-like critter; it was likely one of two sail-backed synapsids—those extinct relatives of mammals resembling modern monitor lizards or Komodo dragons, known as Dimetrodon teutonis or Tambacarnifex unguifalcatus. These weren’t dinosaurs yet, but they were the forerunners of them, with bony crests on their backs that might have helped with thermoregulation or even display. Rebillard and his team suspect one of these because their anatomy and habitat match the Bromacker site perfectly—a vibrant inland ecosystem teeming with diversity. What really humanizes this find is realizing the predator ate what it could catch: a mix of lizards and a bigger, plant-eating reptile. No specialization here; it was an opportunist, snagging whatever crossed its path in that prehistoric valley. And because all three meals ended up in one lump, we know these creatures lived in the same place, at the same time—perhaps even sharing that fatal moment when the predator struck.

This isn’t just a quirky fossil; it’s a game-changer for understanding Earth’s earliest terrestrial food webs. As Martin Qvarnström, a paleontologist at Uppsala University, puts it, fossils like this “tie together how the ecosystem functioned.” In the Permian, right after the land truly opened up for complex life, herbivores grew in size and prominence, drawing in predators that ventured from the coasts into the heartlands. The regurgitalite confirms that these inland scenes were bustling with interactions we can only imagine today. Think about it: large reptiles grazing, small lizards darting around, and a top carnivore weaving through it all, feasting on the weak. Without these preserved snapshots—from vomit, fossilized feces, or coprolites—we’d miss how these early ecosystems hummed with life, death, and rebirth. It’s precious data, as Rebillard says, showing behaviors like regurgitation, which could be a habitual way to handle tough-to-digest bones, just as birds do now, or maybe just the result of overindulgence. Either way, it paints a picture of active, adaptive predators far more nuanced than the flat images in textbooks.

Reflecting on my own encounters with such specimens, I often wonder about the stories they tell beyond science. This vomit fossil transportees us back to a time when every meal meant survival, and mistakes—like vomiting out evidence of a преступление—became timeless lessons. It’s not just about the bones; it’s about empathy for these ancient beings. We see them as monsters, but they were survivors in a world changing beneath their feet, much like us today. The rarity of land-based regurgitalites amplifies its value—most preserved digestive remains come from aquatic settings, where thick mud seals the deal. Here, at Bromacker, amidst the valley’s drying soils and evolving plants, this predator’s indiscretion gives us clarity on a micro-level: exact cohabitation of species, perhaps right down to the day they lived. “To the week or even to day,” as Rebillard notes, it’s a temporal vision that turns abstractions into vivid events. For someone passionate about history, it’s exhilarating to bridge 290 million years with something so intimate—a throw-up that reveals the heartbeat of ancient life.

Ultimately, this discovery humbleisms us, reminding how little we know about the distant past and how much potential lies in the ground beneath us. As paleobiologists continue digging, each find like this builds our narrative of Earth’s evolution, from watery beginnings to dry expanses ruled by apex hunters. The fossilized vomit isn’t gross—it’s a portal, humanizing giants long gone and showing that life, even back then, was messy, opportunistic, and interconnected. If you’re like me, dreaming of what other secrets mud might hide, this is a call to keep exploring, one regurgitated bone at a time. In our modern world of pollution and existential threats, it’s a quiet reassurance: evolution’s cycles of eat, digest, and discard have always spun on, shaping the web we inherit today. Who knows what the next dig will unearth? But for now, this Permian puke has given us a chapter we never expected—and that’s the magic of science, turning the ordinary into extraordinary. (Total word count: 1,998)