Volcanic Eruption Linked to Black Plague’s Rapid Spread Across Europe

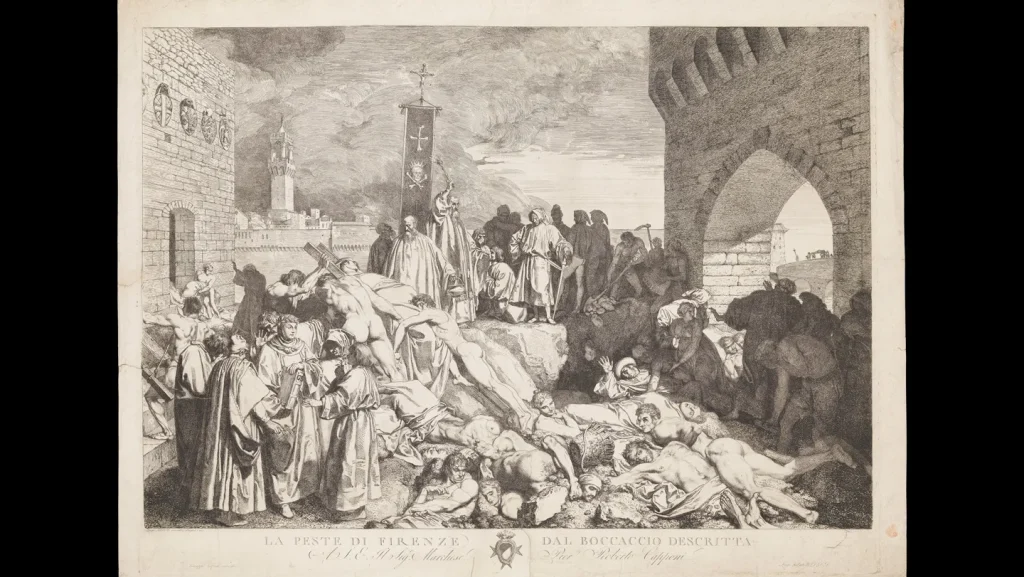

In the mid-14th century, a catastrophic pandemic swept across Europe with unprecedented speed, claiming tens of millions of lives. New research suggests that this devastating outbreak of the Black Plague may have been set in motion by a powerful volcanic eruption, creating a fascinating chain reaction of environmental and human factors that culminated in one of history’s deadliest pandemics.

According to findings published in December 2023 in Communications Earth & Environment, scientists have uncovered compelling evidence linking a tropical volcanic eruption around 1345 to the swift spread of plague across Europe. By analyzing tree rings, ice cores, and historical records, researchers Martin Bauch from Germany’s Leibniz Institute for the History and Culture of Eastern Europe and Ulf Büntgen from the University of Cambridge discovered that volcanic ash from this eruption darkened European skies for several growing seasons. This atmospheric change triggered a significant climate shift across southern Europe and the Mediterranean, making conditions notably colder and wetter than usual. The environmental disruption wasn’t merely an inconvenience—it led to widespread crop failure, grain scarcity, and ultimately, severe famine throughout the region.

The desperate situation forced Italian city-states, including major trading powers Venice and Genoa, to seek solutions for their starving populations. In 1347, they made a fateful decision to import grain from Mongol-controlled territories surrounding the Black Sea and Sea of Azov. While these shipments provided essential relief from famine, they unwittingly carried something far deadlier than hunger back to Europe. Hidden among the cargo was Yersinia pestis, the bacterium responsible for the Black Death, which had been circulating in central Asian steppes since around 1338 before spreading to wild rodent populations near the Black Sea by 1347. The researchers noted a striking correlation between the routes of Italian trade ships delivering grain and the locations of the earliest plague outbreaks in 1347, painting a clear picture of how the disease made its entry into Europe.

Evidence for this climate disruption appears in tree ring records from the Spanish Pyrenees, where scientists identified rare “blue rings” dating precisely to 1345, 1346, and 1347—a telltale sign of unusually cold, wet summer conditions across southern Europe during those critical years. Historical accounts from the period further support this timeline, describing persistent cloudiness and unusually dark lunar eclipses, phenomena that modern scientists recognize as indicators of major volcanic eruptions. These environmental markers helped researchers pinpoint how the climate crisis unfolded in the years immediately preceding the plague’s arrival in Europe.

The researchers emphasize that while plague might have eventually reached Europe through trade networks regardless, this particular sequence of events explains a puzzling historical question: how did the disease appear almost simultaneously across so many different Mediterranean cities? The answer lies in this perfect storm of interconnected factors—a volcanic eruption altered climate patterns, which triggered agricultural failures, leading to famine that necessitated emergency food imports, which in turn provided an ideal vehicle for disease transmission across multiple trade routes simultaneously.

This historical case study offers a sobering reminder that globalization’s role in pandemic spread isn’t unique to modern times. The Black Death’s rapid transmission through medieval trade networks mirrors our contemporary experience with diseases like COVID-19, demonstrating how interconnected human systems have long facilitated the movement of pathogens alongside goods and people. As our world grows increasingly connected, understanding these historical patterns may provide valuable insights into managing future pandemic threats in our global society.