Over the past five years, we’ve seen COVID-19 unfold as a virus that has completely changed our understanding of disease spread, hospitalization, and healthcare systems. However, there are still questions simmering beneath the surface, particularly about how best to manage the pandemic, both at the individual and population level. Here are a few key takeaways that highlight some of the most pressing issues and emerging challenges:

One of the biggest questions is: How can we more effectively predict the spread of COVID-19 to create a safer population? The uncertainty surrounding the virus’s mutations, seasonality, and genetic diversity means that models we’ve built for flu prevention alone can’t fully capture what’s happening here. We’re still trying to understand how transmittability changes with temperature, humidity, and even humidity from water droplets in public hangouts. Without better prediction tools, we risk overestimating cases and underestimating numbers. But just thinking about it, perhaps, as the virus spreads naturally from inputs like droplets, people, andJTIs, even if we don’t know all the details, it feels overwhelming. That’s why fighting COVID-19 is so hard—it’s a game without a winner.

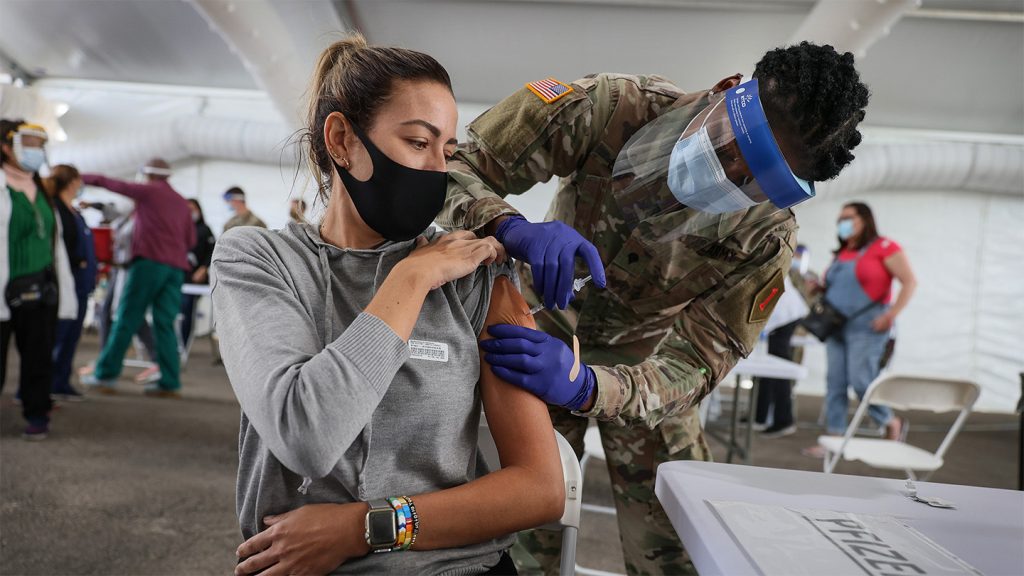

Another important question is: What’s the effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines? While the science of COVID-19 vaccines was relatively mature in the past few years, there are significant uncertainties when it comes to assessing their efficacy. The threshold for success is often elusive—whether a vaccine works just depends on how closely its data aligns with real health outcomes. Even some of the most advanced vaccines, like mRNA-based vaccines, have faced doubts about their safety and long-term protection. For example, some months have seen conflicting reports about how many people were protected versus how many might have required hospitalization. This lack of clarityaccentuates the uncertainty surrounding the vaccine’s full impact, making it so much harder to move forward with future pandemic preparedness.

Yet another issue is: How can we optimize testing strategies, especially considering the rapid pace of the disease and the need for timely diagnosis? Testing is a critical component of managing COVID-19, but modern testing technologies like RT-PCR are proving to be too sensitive to detect even tiny numbers of infected individuals. This leads to what they’ve called “false negatives high”. Even if a lab test indicates a positive, it doesn’t always confirm infection, which can lead to complications like respiratory issues or even alternative reproductive strategy in newborns. This_pm’s also highlights a potential depth of insight into human biology that is yet to be grasped, as even tested individuals can test negative without having been sick. This can’t prevent death or harm from the virus, but it does make managing the disease more difficult.

Additionally, the question of detecting SARS-CoV-2 in real-time is becoming increasingly important, particularly given the growing importance of real-time testing in addressing the pandemic. Here lies a challenge—testing swabs from droplets that are incubating, or even Bits in partnerships, is more complicated than it seems. Studies have shown that some officials from reliable companies provide unreliable。” results, which can lead to scattered attention, fewer discoveries from serums and antiviral medications, and higher rates of mild cases. This inefficiency not only reduces the overall effectiveness of the fight against the pandemic but also contributes to higher mortality rates. Moreover, the lack of testing infrastructure in some countries means that infected individuals with SARS-CoV-2 and recoveries from severe corona virus syndrome (severe symptomatic COVID-19) cannot receive the critical care they require, forcing those cases into the emergency room. This, in turn, isolates the individual and prevents them from receiving timely medical attention, which is crucial for recovery and preventing complications.

When it comes to overcoming stereotypes, misinformation, and uncertainty, one approach is to focus more on what we can control—how we can administer the vaccine, reduce infection transmission, and prioritize care. But to do all that, we need better infrastructure, expertise, and collaboration. Here’s a scenario: during the waves of COVID-19, some of the world’s best-prepared populations tried to lift protective measures, but unfortunately missing the chance to implement better-quumped antibodies or better strategies. This allowed the virus to cluster, spread, and eventually convictions. The only way to truly fight this is to not let the system get distracted and to instead actively stance it.

Finally, what neglects? Think about how we build our healthcare systems—how do we detect SARS-CoV-2, how do we administer vaccines, and how do we focus critical resources where they matter most. Paper shortages, supply chains, andembedement of healthcare are all real issues that need to be addressed. But perhaps, as a universal catalyst, the lack of robust testing infrastructure in some countries is one thing, but the belief in theirACK toward that as the only way of making their healthcare systems work is another.