The International Space Station (ISS), a symbol of international collaboration in space, has been orbiting Earth since 1998. Its creation involved a multinational agreement between the U.S., Russia, Japan, Canada, and eleven European nations, explicitly dedicated to peaceful scientific endeavors. However, China was notably excluded from this initial partnership. Almost a decade later, China expressed a desire to participate in the ISS project, garnering support from the European Space Agency and South Korea. Despite this international backing, the United States ultimately blocked China’s inclusion, citing security concerns rooted in legislation passed by Congress in 2011. This legislation prohibited collaboration with China on certain scientific research, especially in space, due to concerns about the opacity of China’s space program and its perceived close ties to the Chinese military.

This exclusion spurred China to independently develop its own space station program. Between 2011 and 2018, China launched and subsequently deorbited two temporary space labs, gaining valuable experience and demonstrating its growing capabilities. In 2021, China launched the core module of its permanent space station, Tiangong, or “Heavenly Palace,” marking a significant achievement in its space ambitions. This development has heightened concerns within the U.S. about falling behind in the renewed “space race” and the potential geopolitical implications of China’s growing dominance in low Earth orbit. The U.S. now faces the challenge of ensuring the continuity of its presence in space as the ISS nears the end of its operational life.

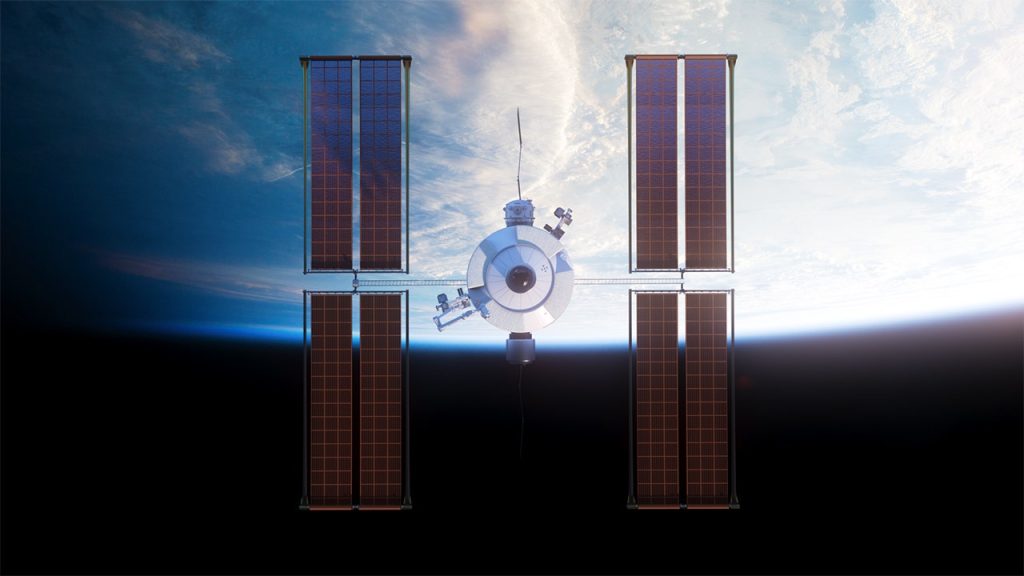

NASA is actively working with private companies like Voyager Space to develop commercially operated space stations to succeed the ISS. Voyager’s Starlab is projected to launch in 2028, but concerns linger about potential funding shortfalls and delays. These delays raise the unsettling prospect of the ISS being decommissioned before a replacement is ready, leaving China as the sole operator of a space station. This scenario evokes parallels with the retirement of the Space Shuttle program in 2011, which left the U.S. reliant on Russia for access to space for several years.

The Space Shuttle program, a pioneering endeavor in reusable spacecraft technology, was retired under President George W. Bush’s vision for a new space exploration initiative. The plan included developing a new Crew Exploration Vehicle to replace the Shuttle, but budgetary constraints and program delays during the Obama administration led to its cancellation. Instead, the government invested in commercial space companies to develop crew transportation capabilities. While this ultimately led to the successful development of commercially operated spacecraft like SpaceX’s Dragon, it also resulted in a nine-year gap in American human spaceflight capabilities, highlighting the risks of transitioning between major space programs.

NASA officials maintain that the current situation is different from the Shuttle era, emphasizing the U.S.’s continued leadership in space exploration and its strong international partnerships. However, the fact remains that only Chinese astronauts, or “taikonauts,” have visited the Tiangong station. China has expressed willingness to host astronauts from other nations and has increased cooperation with countries like Sweden, Russia, and Italy. Furthermore, the recent launch of China’s first international payload on a commercial rocket, carrying Oman’s first satellite, signals China’s growing influence in the global space arena.

This evolving landscape raises concerns about the potential for technology transfer and the strategic implications of relying on China for access to space. If China becomes the sole provider of long-duration low Earth orbit access, international partners and commercial companies might have little choice but to collaborate with China, potentially compromising sensitive technologies and further solidifying China’s position as a dominant space power. American companies like Arkisys are developing technologies like robotic servicing ports to maintain a U.S. presence in space, even if a commercial space station is not immediately available after the ISS retirement. This interim solution could serve as a bridge to the next generation of space stations, ensuring continued American involvement in space research and exploration.