Trump Seeks Death Penalty Revival in Washington, D.C. Amid Crime Crackdown

President Donald Trump has made waves with his recent announcement regarding the reintroduction of the death penalty in Washington, D.C., for those convicted of murder. During an August Cabinet meeting, while discussing his administration’s efforts to combat crime in the nation’s capital, Trump stated firmly, “If somebody kills somebody in the capital, Washington, D.C., we’re going to be seeking the death penalty.” This declaration comes as part of a broader crime reduction strategy that has already seen the deployment of hundreds of D.C. National Guard troops, resulting in more than 1,600 arrests since mid-August. Trump characterized capital punishment as “a very strong preventative” measure, adding, “everybody that’s heard it agrees with it.” Despite his conviction, the implementation of such a policy faces significant legal and jurisdictional complexities in a district where capital punishment has been absent for decades.

The president’s push for capital punishment in D.C. highlights an interesting jurisdictional dynamic between local and federal authority in the nation’s capital. While Washington’s Superior Court, which handles local matters, has been barred from utilizing the death penalty since its official rescission by the D.C. Council in 1981, the death penalty remains legal at the federal level. According to Matthew Cavedon, director of the Cato Institute’s Project on Criminal Justice, Trump’s strategy would involve the Department of Justice prosecuting major crimes through the United States Attorney’s Office—now led by Jeane Pirro—bringing cases in U.S. District Court rather than through D.C.’s internal court system. This approach would effectively circumvent the local prohibition on capital punishment by elevating murder cases to federal jurisdiction, where the death penalty remains an available sentencing option despite the District’s long-standing opposition to capital punishment.

Trump’s advocacy for the death penalty is not new. In January, he issued an executive order titled “Restoring the Death Penalty and Protecting Public Safety,” which directs the attorney general to “pursue the death penalty for all crimes of a severity demanding its use.” The order emphatically states that “capital punishment is an essential tool for deterring and punishing those who would commit the most heinous crimes and acts of lethal violence against American citizens.” It further argues that throughout American history, from the founding era to the present, “our cities, States, and country have continuously relied upon capital punishment as the ultimate deterrent and only proper punishment for the vilest crimes.” When combined with his recent statements, these actions indicate Trump’s intention to instruct federal prosecutors to aggressively seek the death penalty in Washington murder cases, regardless of local sentiment or policy.

The national landscape regarding capital punishment presents a divided picture, with 27 states permitting the death penalty and 23 prohibiting it. Among those that technically allow it, four states—California, Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Oregon—currently have gubernatorial holds on executions. Cavedon suggests that Trump’s push might inadvertently accelerate abolition efforts in states that still maintain the death penalty on their books but rarely use it, noting that “something like the president calling for lots and lots of executions might be enough to tip things over and get places like California to just do away with the death penalty on the state side.” This potential for backlash highlights the controversial nature of capital punishment in contemporary American society, where opinions remain deeply divided along political, moral, and practical lines.

Critics of Trump’s death penalty initiative, such as Georgetown Law professor Cliff Sloan, who teaches constitutional law and death penalty litigation, argue that the proposal is unnecessary on multiple grounds. Sloan points out that the homicide rate in Washington has actually been declining, undermining the premise that drastic measures are needed to address an escalating crisis. More fundamentally, he challenges the assumption that capital punishment effectively deters murder, noting that “there is absolutely no correlation between the death penalty and a reduction in homicides.” He cites evidence that states without the death penalty have not experienced increases in homicide rates after abolition, while states that actively impose capital punishment often have higher murder rates. These observations call into question the deterrent value that forms a central justification for Trump’s policy proposal.

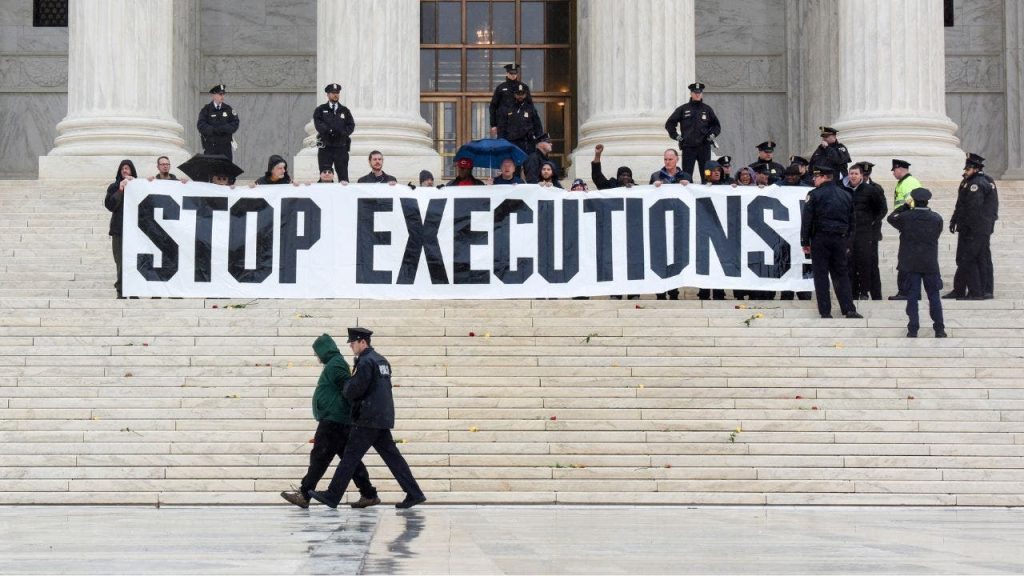

Public opinion on the death penalty continues to evolve, with support showing a gradual but consistent decline over recent decades. According to a Gallup poll from November, 53% of Americans still favor capital punishment, but this represents a five-decade low in public approval. This shifting sentiment reflects broader discussions about criminal justice reform, concerns about the irrevocable nature of execution in a system where wrongful convictions do occur, and questions about whether the practice aligns with evolving standards of justice and human rights. As Trump pushes forward with his plan to revitalize the death penalty in Washington, D.C.—a jurisdiction that hasn’t conducted an execution since 1957 and whose residents explicitly rejected capital punishment in a 1992 referendum—these tensions between federal authority, local governance, crime control strategies, and evolving public values are likely to intensify, creating yet another flashpoint in America’s ongoing debates about crime, punishment, and the proper limits of governmental power.