The Global Shift Toward Assisted Death: A New Frontier in Personal Autonomy

As More Countries Legalize Medical Assistance in Dying, Complex Questions Emerge

By Stephanie Nolen | Dec. 9, 2025

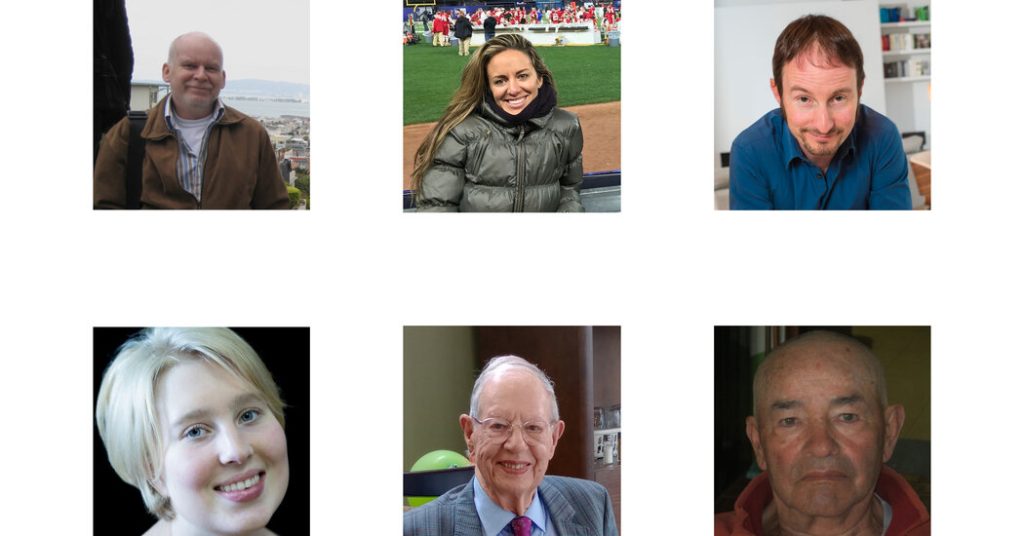

Ron Curtis, an English professor in Montreal, lived for 40 years with a degenerative spinal disease that trapped him in what he called the “black hole” of chronic pain. On a July day in 2022, after enjoying a final bowl of vegetable soup prepared by his wife Lori, the 64-year-old died peacefully in his bedroom overlooking a lake, with the assistance of a palliative care doctor.

In Belgium, successful stage and television actor Aron Wade, 54, could no longer endure the depression that had haunted him for three decades. After a medical panel determined he experienced “unbearable mental suffering,” a doctor came to his home and administered medication that stopped his heart, with his partner and two best friends by his side.

Argemiro Ariza, in his early 80s, began losing function in his limbs and could no longer care for his wife with dementia in their Bogotá home. After doctors diagnosed him with ALS, he told his daughter Olga that he wanted to die with dignity. His children threw him a farewell party with a mariachi band and lifted him from his wheelchair to dance. Days later, he received hospital-administered medication that ended his life.

Until recently, each of these deaths would have been classified as murder. Today, they represent a monumental global shift in how societies approach end-of-life care and individual autonomy. From liberal European nations to conservative Latin American countries, a fundamental reconsideration of death is taking hold.

A Rapid Global Expansion of End-of-Life Rights

Over the past five years, physician-assisted death has been legalized in nine countries across three continents. Courts or legislatures in a half-dozen more nations, including South Korea and South Africa, along with eight U.S. states where it remains prohibited, are actively considering legalization.

This represents the last frontier in expanding individual autonomy. More people are seeking to define their deaths in the same way they’ve controlled other aspects of their lives, such as marriage and childbearing. This trend extends even to Latin America, where conservative institutions like the Roman Catholic Church maintain significant influence.

“We believe in the priority of our control over our bodies, and as a heterogeneous culture, we believe in choices: If your choice does not affect me, go ahead,” explains Dr. Julieta Moreno Molina, a bioethicist who has advised Colombia’s Ministry of Health on assisted dying regulations.

Yet as assisted death gains broader acceptance, profound questions arise about eligibility. While most jurisdictions initially limit access to those with terminal illness—which garners the most public support—pressure to expand access often follows quickly, sparking intense societal debate.

Should Someone with Intractable Depression Be Allowed an Assisted Death?

European countries and Colombia permit individuals with irremediable suffering from conditions like depression or schizophrenia to seek assisted death. In Canada, however, this issue has become deeply contentious. While assisted death for people without a reasonably foreseeable natural death was legalized in 2021, the Canadian government has repeatedly excluded those with mental illness. Two individuals are now challenging this exclusion in court, arguing it violates their constitutional rights.

Those supporting assisted death for mental health conditions argue that individuals who have endured severe depression for years and exhausted various therapies and medications should be allowed to determine when they no longer wish to pursue further treatments. Opponents raise concerns that mental illness can involve a pathological desire to die, making it difficult to predict treatment effectiveness. They also worry that inadequate access to mental health care might lead people to choose death when their conditions could potentially improve with proper treatment.

Denise de Ruijter, diagnosed with autism, experienced episodes of depression and psychosis. As a teenager in the Netherlands, she craved the social connections her peers enjoyed—nights out, relationships—but couldn’t manage them. After multiple suicide attempts, she applied for assisted death at 18. Evaluators required her to try three additional years of therapy before determining her suffering was unbearable. She died in 2021, surrounded by family and her beloved Barbie dolls.

Should a Child with an Incurable Condition Be Able to Choose Assisted Death?

The capacity to consent is fundamental when requesting assisted death. Only a handful of countries extend this right to minors. Even in jurisdictions that do, pediatric assisted deaths remain rare, typically involving children with cancer.

In Colombia and the Netherlands, children over 12 can independently request assisted death, while parents can provide consent for those 11 and younger. This issue has come under renewed scrutiny in the Netherlands, where a growing number of adolescents have sought assisted death for psychiatric suffering from conditions like eating disorders and anxiety over the past decade.

Most such applications are either withdrawn or rejected, but public concern over high-profile cases of teenagers receiving assisted deaths has prompted the Dutch regulator to consider temporarily suspending approvals for children applying based on psychiatric suffering.

Should Someone with Dementia Be Allowed Assisted Death?

Many people fear losing cognitive abilities and autonomy, hoping to access assisted death when they reach that stage. But this presents more complex regulatory challenges than for someone who can clearly articulate their wishes.

How can someone with diminishing mental capacity consent to dying? Most governments and medical professionals remain uncomfortable permitting this, even though the concept typically enjoys support in countries with aging populations.

In Colombia, Spain, Ecuador, and Quebec, individuals diagnosed with Alzheimer’s or other cognitive decline can request assessment for assisted death before losing mental capacity and sign an advance request—allowing a physician to end their life after they’ve lost the ability to consent.

This raises another challenging question: After people lose the capacity to request assisted death, who decides when it’s time? Colombia entrusts families with this responsibility, while the Netherlands leaves it to doctors—though many refuse to administer lethal medication to patients who cannot clearly articulate a rational wish to die.

Jan Grijpma, 90, was always clear with his daughter Maria: when his mind deteriorated, he didn’t want to continue living. Maria collaborated with his longtime Amsterdam family doctor to identify when Mr. Grijpma, living in a nursing home, was approaching the point of losing his ability to consent. When that moment neared in 2023, they scheduled the procedure, and he methodically updated his day planner: “Thursday, visit the vicar; Friday, bicycle with physiotherapy and get a haircut; Sunday, pancakes with Maria; Monday, euthanasia.”

Who Has Broken the Taboo?

For decades, Switzerland stood alone in permitting assisted death; assisted suicide was legalized there in 1942. Another half-century passed before a few more countries liberalized their laws. Recently, decriminalization has spread across Europe.

Latin America has experienced a wave of legalization, where Colombia had been an outlier since allowing legal assisted dying in 2015. Paola Roldán Espinosa, a successful business professional in Ecuador with a young child, was diagnosed with ALS in 2023. As her condition rapidly deteriorated, requiring ventilator support, she sought to die on her terms and petitioned Ecuador’s highest court. In February 2024, the court responded by decriminalizing assisted dying. At 42, Roldán had the death she sought a month later, surrounded by family.

Ecuador decriminalized assisted dying through constitutional court cases, while Peru’s Supreme Court has permitted individual exceptions to prohibitive laws, potentially opening doors to expansion. Cuba’s national assembly legalized assisted dying in 2023, though regulations aren’t yet established. In October, Uruguay’s parliament passed legislation allowing assisted death for the terminally ill after extensive debate.

South Korea is taking initial steps toward legalization, with a bill to decriminalize assisted death repeatedly proposed in the National Assembly. Simultaneously, the Constitutional Court, which previously declined such cases, has agreed to adjudicate a petition from a disabled man with severe chronic pain seeking assisted death.

In the United States, access remains limited: 11 jurisdictions allow assisted suicide or physician-assisted death for patients with terminal diagnoses, sometimes only for those already in hospice care. Delaware will implement legalization on January 1, 2026.

Slovenia presents a complex case: in 2024, 55 percent of referendum voters favored legalizing assisted death, with parliament passing corresponding legislation in July. However, opposition from right-wing politicians forced a second referendum, where 54 percent of voters rejected legalization in late November.

The United Kingdom is considering legislation to permit assisted death for terminally ill individuals, facing strong opposition from more than 60 disability advocacy groups. These organizations argue that disabled individuals might face subtle coercion to end their lives rather than burden families or strain state resources for their care.

Why Now?

In many countries, assisted dying decriminalization has followed expanded rights for personal choice in other areas, such as same-sex marriage, abortion, and sometimes drug use.

“I would expect it to be on the agenda in every liberal democracy,” says Wayne Sumner, a medical ethicist at the University of Toronto who studies the evolution of norms around assisted dying. “They’ll come to it at their own speed, but it follows with these other policies.”

This shift is driven by converging political, demographic, and cultural factors. Aging populations and improved healthcare access mean more people living longer, often with chronic conditions. These individuals are contemplating death and determining what they will—and won’t—tolerate in their final years. Simultaneously, there’s decreasing tolerance for suffering perceived as unnecessary.

“Until very recently, we were a society where few people lived past 60—and now suddenly we live much longer,” explains Lina Paola Lara Negrette, a psychologist who until October directed Colombia’s Dying With Dignity Foundation. “Now people here need to think about the system, and the services that are available, and what they will want.”

Changes in family structures, particularly in rapidly urbanizing middle-income countries, have weakened traditional care networks, shifting perceptions about living with chronic illness or advanced age. “When you had many siblings and a lot of generations under one roof, the question of care was a family thing,” Negrette notes. “That has changed. And it shapes how we think about living, and dying.”

How Does Assisted Dying Work?

Beyond ethical considerations, implementing legalized assisted death involves countless practical decisions. Spain requires at least 15 days between patient assessments, though the average wait extends to 75 days. Most jurisdictions prescribe waiting periods under two weeks for terminal patients, but actual waits are often longer, according to Katrine Del Villar, constitutional law professor at Queensland University of Technology.

Most countries allow patients to choose between self-administering drugs or having healthcare providers administer them. When both options exist, the vast majority select provider-administered medication that stops their heart.

While many countries restrict drug administration to physicians, Canada and New Zealand also permit nurse practitioners to provide assisted deaths. One Australian state prohibits medical professionals from initiating discussions about assisted death—patients must raise the topic first.

Eligibility determination varies: the Netherlands requires assessment by two physicians; Colombia employs a panel including a medical specialist, psychologist, and lawyer; Britain’s draft legislation would require both a panel and two independent physicians.

Switzerland and the U.S. states of Oregon and Vermont are the only jurisdictions explicitly allowing non-residents access to assisted deaths.

Most countries permit individual healthcare professionals to conscientiously object to providing assisted deaths and allow faith-based institutions to decline participation. In Canada, while individual professionals can refuse, a legal challenge seeks to end the ability of publicly-funded faith-based hospitals to prohibit assisted deaths on their premises.

“Even when assisted dying has been legal and available somewhere for a long time, there can be a gap between what is legal and what is acceptable—what most physicians and patients and families feel comfortable with,” observes Dr. Sisco van Veen, ethicist and psychiatrist at Amsterdam Medical University. “And this isn’t static. It evolves over time.”

Reporting contributed by Jin Yu Young in Seoul, José Bautista in Madrid, José María León Cabrera in Quito, Veerle Schyns in Amsterdam and Koba Ryckewaert in Brussels.