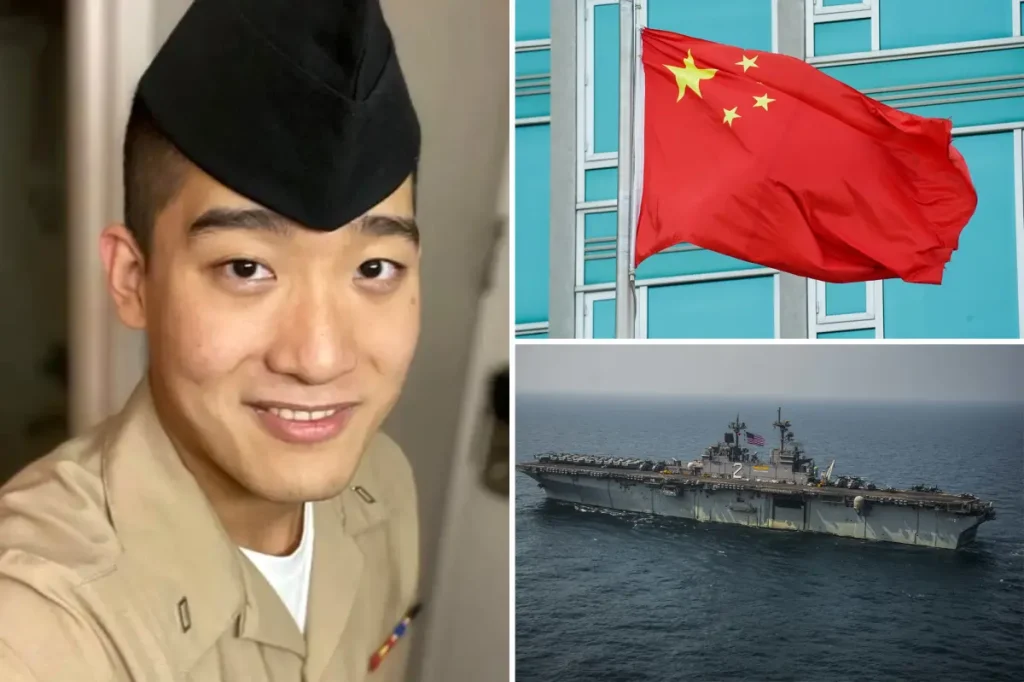

Naval Betrayal: The Story of a US Navy Sailor Who Spied for China

In a striking case of modern espionage, 25-year-old Jinchao Wei, a China-born US Navy sailor, was sentenced to 16 years in prison for selling sensitive military information to Chinese intelligence. The federal judge in San Diego who handed down the 200-month sentence described Wei as a “traitor” who compromised American national security for personal gain. Over 18 months, Wei received more than $12,000—approximately 20% of his annual Navy salary—for providing photographs, videos, and technical manuals detailing US Navy systems and operations to his Chinese handler. “This active-duty US Navy sailor betrayed his country and compromised the national security of the United States,” stated Deputy Attorney General Todd Blanche, underscoring the severity of Wei’s actions against the nation he had sworn to protect.

Wei’s journey into espionage began innocuously enough through social media, but quickly escalated into something far more sinister. While applying for US citizenship in February 2022, Wei was contacted by a man he would later call “Big Brother Andy,” who initially presented himself as a naval enthusiast working for China’s state-owned shipbuilding corporation. Court evidence revealed that Wei suspected early on that his contact was actually a Chinese military intelligence officer. In messages to a friend, Wei described the individual as “extremely suspicious” and recognized that the request to “walk the pier” to observe docked ships was “quite obviously f–king espionage.” Despite these misgivings, Wei established a relationship with the intelligence officer and began supplying sensitive information about the USS Essex, including ship locations and weapons details, through encrypted messaging applications.

The relationship between Wei and his Chinese handler became increasingly sophisticated as they employed various techniques to avoid detection. The handler used encrypted applications for their communications, regularly wiped messages and accounts, utilized 72-hour digital “dead drops” for information transfer, and even provided Wei with a new phone and computer to maintain operational security. This level of tradecraft suggests that the Chinese intelligence services were investing significant resources in Wei as an asset. Over time, Wei escalated his betrayal by selling at least 30 technical and operational manuals on US Navy systems—a major intelligence coup for China. The prosecution presented a wealth of evidence at trial, including calls, texts, and audio messages that documented their communication patterns, assigned tasks, cover-up efforts, and payment mechanisms.

Perhaps one of the most disturbing aspects of this case was the role played by Wei’s mother. According to prosecutors, she not only knew about her son’s espionage activities but actively encouraged him to continue, believing it might secure him future employment with the Chinese government. The intelligence officer had even offered to fly both Wei and his mother, who resides in Wisconsin, to China for an in-person meeting. Investigators discovered that Wei had searched online for flights to China prior to his arrest, suggesting he may have been considering defection. This familial dimension adds another layer of complexity to Wei’s betrayal, raising questions about divided loyalties within immigrant families and the pressure that can sometimes exist to maintain connections with one’s country of origin, even at the expense of adopted allegiances.

In his defense, Wei attempted to downplay his actions. Days before sentencing, he submitted a handwritten letter to the judge acknowledging his mistake: “Yes, I screwed up.” His attorneys sought a much lighter 30-month sentence, arguing that Wei genuinely believed his Chinese contact was merely a naval enthusiast working for a shipbuilding company, not an intelligence officer. They maintained that his actions were not motivated by “any hatred or animosity towards the US government, nor were they a means to get rich.” However, this portrayal contradicted evidence showing Wei’s awareness of the espionage nature of his activities. In August, Wei was convicted of conspiracy to commit espionage, espionage, and unlawful export of technical data related to defense articles in violation of the Arms Export Control Act and International Traffic in Arms Regulations. The jury found him not guilty on one count of naturalization fraud.

Wei’s case represents one of several recent instances of alleged Chinese espionage targeting the American military. He was one of two California-based sailors charged with spying for China in 2024. The other defendant, Wenheng Zhao, received a lighter sentence of just over two years after pleading guilty to conspiracy and accepting bribes in violation of his official duties. These cases highlight ongoing concerns about China’s aggressive intelligence gathering efforts aimed at American military technology and capabilities. They also underscore the vulnerabilities that can exist when service members face conflicting loyalties or financial temptations. For national security experts, Wei’s case serves as a sobering reminder of the persistent threat of insider threats and the need for robust counterintelligence measures within the U.S. military. Meanwhile, for Wei himself, his decision to betray his adopted country for $12,000 has resulted in the loss of 16 years of his life—a steep price for momentary gain.