Rising Tides of Change: How Human Activity is Reshaping Earth’s Marine Ecosystems

Coastal Communities Face Unprecedented Transformation as Sea Life Adapts to Multiple Threats

By Diana Richardson, Marine Science Correspondent

September 4, 2025

On a sweltering summer day on St. Helena Island, South Carolina, Ed Atkins stands on a weathered dock, pulling a five-foot cast net from the water. With practiced movements, he dumps a handful of glossy white shrimp onto the wooden planks – a small harvest from the salt marsh that has sustained his family for generations.

“When they passed, they made sure I tapped into it and keep it going,” Atkins says of the bait shop his parents established in 1957. “I’ve been doing it myself now for 40 years.”

The coastal marshes that underpin Atkins’ livelihood represent the blurred boundary between land and sea – crucial nursery habitats for countless marine species and the foundation for commercial and recreational fisheries that generate billions in economic activity. But these seemingly timeless seascapes have become some of the planet’s most vulnerable marine ecosystems, according to groundbreaking research published Thursday in the journal Science.

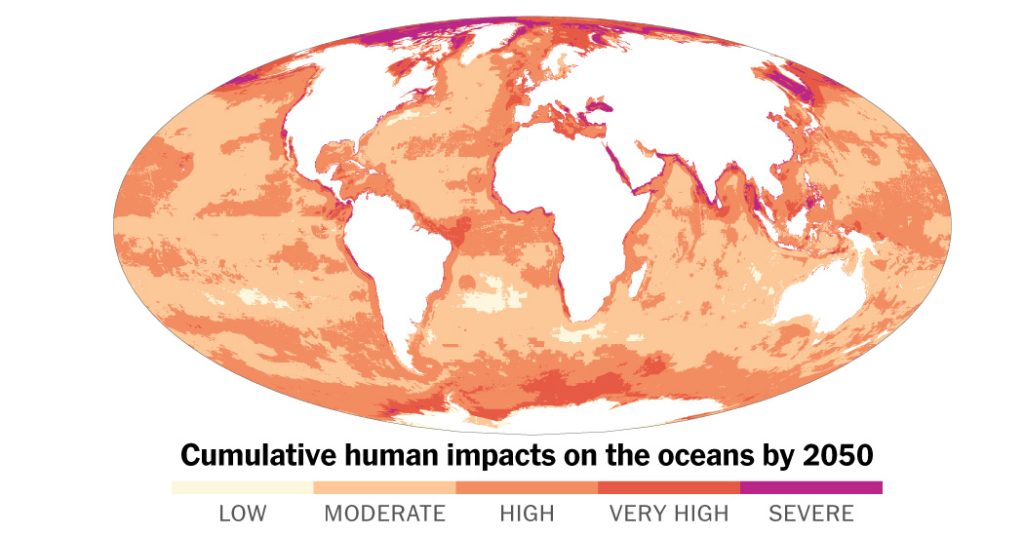

The comprehensive study, which maps and quantifies how human activity is reshaping oceans worldwide, delivers a sobering prediction: many of Earth’s marine ecosystems could be fundamentally and permanently altered if current pressures like climate change, overfishing, ocean acidification, and coastal development continue unabated.

“It’s death by a thousand cuts,” explains Ben Halpern, marine biologist and ecologist at the University of California, Santa Barbara, and one of the study’s lead authors. “It’s going to be a less rich community of species. And it may not be something we recognize.”

A Global Transformation Underway

The research identifies several coastal ecosystems at particularly high risk, including salt marshes, seagrass meadows, rocky intertidal zones, and mangrove forests. These nearshore environments – the ocean areas humans most depend upon – provide natural storm buffers, support biodiversity, and sustain the vast majority of commercial and recreational fishing, which supports more than two million American jobs alone.

For the Gullah Geechee people like Atkins, descendants of enslaved West Africans who worked plantations along the Southeastern coast, the stakes extend beyond economics to cultural identity and heritage.

“We have our own language, we have our own food ways, we have our own ecological system here,” explains Marquetta Goodwine, elected head of the Gullah Geechee Nation and a leader in coastal protection efforts. The distinctive culture depends on oyster beds, native grasses, and maritime forests that characterize the region’s tidal and barrier islands, collectively known as the Sea Islands.

“You don’t have that, you don’t have a Sea Island,” Goodwine, who also goes by Queen Quet, emphasizes. “You don’t have a Sea Island, you don’t have Gullah Geechee culture.”

Measuring the Unmeasurable

The groundbreaking study represents the culmination of research that began in the early 2000s, when widespread coral bleaching alarmed marine scientists worldwide. Halpern and colleagues developed a method to map ocean regions most and least affected by human activity.

Their approach tackles the inherent challenge of comparing vastly different marine habitats – from coral reefs to the deep ocean floor – and their varied responses to different human pressures. The researchers developed an “impact score” based on a formula incorporating each habitat’s location, the intensities of various pressures, and each ecosystem’s specific vulnerabilities.

Under current trajectories, approximately 3 percent of the global ocean is at risk of transforming beyond recognition by mid-century. But in nearshore environments, where human contact is most direct, that figure jumps dramatically to more than 12 percent.

The transformation will manifest differently across regions. Tropical and polar seas face more pronounced effects than temperate, mid-latitude waters. While human pressures are increasing faster in offshore zones, coastal waters will continue experiencing the most serious impacts, according to projections.

Nations particularly vulnerable to these changes include those most dependent on ocean resources, with Togo, Ghana, and Sri Lanka topping the researchers’ vulnerability index.

Across affected areas, marine ecosystems will likely become ecologically poorer, with reduced biodiversity, Halpern explains. This outcome stems from a simple reality: species resilient against climate change and other anthropogenic pressures are far fewer than vulnerable ones.

Cumulative Impacts Mount

The study identifies ocean warming and overfishing as the biggest current and future pressures on marine ecosystems. However, the researchers acknowledge likely underestimating fishing impacts, as their model assumes fishing activity will remain constant rather than increase. The analysis also focuses solely on targeted species, excluding bycatch and habitat destruction from practices like bottom trawling.

Some human activities remain difficult to fully quantify, including rapidly expanding seabed drilling and mining operations. Another limitation involves the study’s linear approach to calculating cumulative effects, when in reality, combined pressures might create synergistic effects greater than the sum of individual impacts.

“Some of these activities, they might be synergistic, they might be doubling,” notes Mike Elliott, marine biologist and emeritus professor at the University of Hull in England, who wasn’t involved in the study. “And some might be antagonistic, might be canceling.”

Despite these methodological constraints, Elliott agrees with the study’s broad conclusions. Scientists might debate whether cumulative effects will double or triple, he says, “but it will be more, because we’re doing more in the sea.”

“If we wait until we’ve got perfect data,” Elliott adds, “we’ll never do anything.”

Protection and Restoration Efforts Gain Momentum

Studies like this provide crucial guidance for ocean planning and management initiatives, including the global “30×30” effort to place 30 percent of Earth’s land and seas under protection by 2030.

South Carolina’s ACE Basin exemplifies such conservation approaches. This largely undeveloped 350,000-acre wetland, named for the Ashepoo, Combahee, and Edisto rivers that thread through it, presents an otherworldly landscape where visitors often become disoriented amid vast salt marshes stretching in every direction – a vivid tapestry of blues and greens dotted with white wading birds and surfacing dolphins.

In one secluded corner of the marsh, an unusual structure emerges at low tide: concrete blocks arranged like a wall, now nearly hidden beneath thousands of shells. These “oyster castles” – constructed by volunteers from Boeing’s North Charleston assembly plant in collaboration with the Nature Conservancy and South Carolina’s Department of Natural Resources – represent one component in a growing network of living shoreline projects.

These structures protect landscapes from erosion, sea level rise, and storm surges while allowing water to pass through and deposit sediment. Behind the oyster castles, mud accumulates significantly higher than in surrounding areas, allowing marsh grass to take root and flourish.

“We’ve been testing and piloting things for so long, and now is the time to scale it up,” says Elizabeth Fly, director of resilience and ocean conservation at the Nature Conservancy’s South Carolina chapter.

South Carolina’s oyster shell recycling program has established over 200 small living shorelines with volunteer assistance, often partnering with groups like the Gullah Geechee Nation. These projects now span locations from wastewater treatment plants to golf resorts, military bases, boat launches, and private docks.

Many efforts fall under the South Atlantic Salt Marsh Initiative, a collaboration between the Pew Charitable Trusts, Department of Defense, federal agencies, and state governments spanning one million acres of salt marsh across four Southeastern states.

Living with Change

While scientists work to better understand ocean pressures and conservation specialists implement protective measures, coastal communities are already experiencing environmental shifts – both subtle and profound.

In Mount Pleasant, South Carolina, the annual Sweetgrass Festival celebrates traditional Gullah Geechee basketry. Dozens of artisans brave summer heat to display intricate baskets woven from sweetgrass, bulrush, palmetto leaves, and pine needles.

Henrietta Snype, a 73-year-old master basket maker who began practicing at age seven, proudly displays works created by five generations of her family. While dedicated to preserving and teaching this cultural tradition, she acknowledges the changing environment around her.

Climate shifts have brought more frequent and destructive hurricanes, she observes. And basket-making itself has become more challenging as traditional materials grow scarcer. Sweetgrass is diminishing in coastal areas, and harvesters struggle to access gathering sites now located on private or developed property.

“The times bring on a lot of change,” Snype reflects – a simple observation that captures the profound transformations reshaping coastal communities and marine ecosystems worldwide.

As human pressures on oceans continue mounting, the research suggests we’re approaching a crossroads that will determine whether future generations inherit recognizable marine environments or fundamentally altered seascapes. The choices made in coming years – about conservation, development, climate action, and fishing practices – will shape not just ecosystems but the cultures and livelihoods intimately connected to them.

Methodology: Maps and data on human impacts on oceans reflect estimates based on the SSP2-4.5 “middle of the road” scenario, which approximates current climate policy trajectories.