Trump Administration’s Controversial Deportation Plan for MS-13 Gang Member

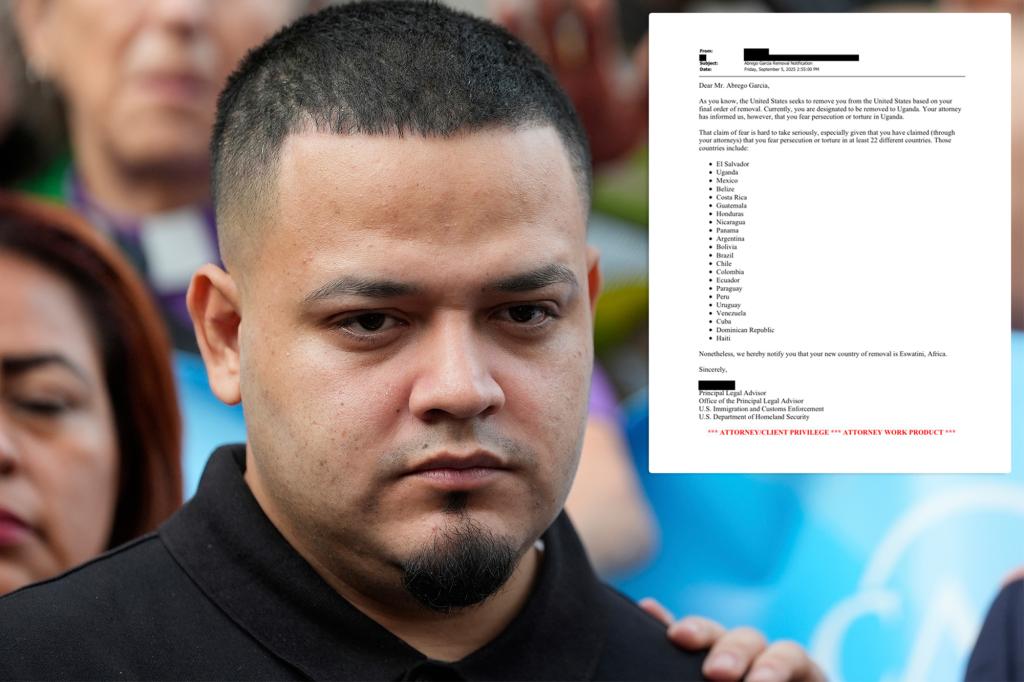

In a surprising turn of events, Kilmar Abrego Garcia, a 30-year-old alleged MS-13 gang member from El Salvador, now faces deportation to Eswatini, a tiny monarchy in southern Africa. This unusual development comes after Garcia rejected a plea deal offered by the Trump administration that would have allowed him to serve a sentence in Costa Rica for human smuggling charges. The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) informed Garcia of this decision in a Friday email, marking yet another controversial chapter in the administration’s aggressive approach to immigration enforcement. Garcia had previously submitted a list of 22 countries where he claimed he could not live due to “fear of persecution or torture,” including Uganda, Mexico, Costa Rica, Guatemala, Panama, Brazil, and several other South American nations. This extensive list of exclusions appears to have led authorities to select Eswatini as his destination—a country rarely mentioned in U.S. immigration proceedings.

Garcia’s case has followed a complex and winding path through the U.S. immigration system. Earlier this year, he was deported to El Salvador, where authorities initially accepted him into custody at the nation’s Terrorism Confinement Center on March 15. However, following a Supreme Court ruling, El Salvador released him back to the United States in June. Upon his return, Garcia was briefly held in Putnam County Jail in Tennessee before being released on August 22 under electronic surveillance and home confinement, allowing him to return to Maryland. This back-and-forth between countries reflects the complicated international politics surrounding deportation cases, especially those involving alleged gang members. The Trump administration had initially planned to deport Garcia to Uganda before shifting focus to Eswatini, seemingly in response to his claims of potential persecution in numerous other countries that might otherwise have been considered.

The decision to send Garcia to Eswatini represents part of a broader pattern, as the Trump administration has already deported five individuals to this small African nation. These deportations have not proceeded without controversy—they’ve already faced significant legal challenges. One such case involves a Jamaican national represented by the Legal Aid Society who claims to have been “inexplicably and illegally” sent to Eswatini despite Jamaica’s willingness to accept him back. DHS has rejected this claim, suggesting a growing tension between the administration’s deportation policies and legal advocacy groups concerned about due process and human rights. The choice of Eswatini—a country with limited connections to Central American migration patterns—raises questions about the criteria being used to determine deportation destinations when traditional repatriation options are contested.

Eswatini itself presents a stark contrast to Garcia’s home country of El Salvador. Formerly known as Swaziland, Eswatini is the last remaining absolute monarchy on the African continent. It’s one of Africa’s smallest countries, landlocked between South Africa and Mozambique. The current monarch, King Mswati III, is known for his polygamous lifestyle with 16 wives and dozens of children. Beyond its unique political structure, Eswatini faces significant socioeconomic challenges, with approximately 32% of its population living below the poverty line according to World Bank data. For someone like Garcia, who has presumably spent most of his life in El Salvador and more recently in the United States, adaptation to such a dramatically different cultural, political, and economic environment would likely present extraordinary challenges—a reality that has fueled criticism of this deportation approach.

Human rights advocates and immigration attorneys have expressed concern about what they see as the arbitrary nature of these deportation decisions. They question whether sending individuals to countries with which they have no cultural, linguistic, or familial ties constitutes a form of additional punishment rather than simply enforcing immigration law. The practice of sending deportees to third countries that are willing to accept them—especially when those countries are significantly different from their homelands—raises serious ethical and legal questions about the boundaries of deportation policy. For Garcia, who allegedly has ties to MS-13, one of the most notorious transnational gangs, the relocation to Eswatini seems designed to maximize his isolation from potential criminal networks, though critics argue this approach prioritizes punishment over more traditional goals of deportation.

As this case continues to develop, it highlights the increasingly complex intersection of immigration enforcement, international relations, and human rights considerations in American policy. The Trump administration’s willingness to pursue unconventional deportation destinations reflects its hardline stance on immigration enforcement, particularly regarding individuals with alleged gang affiliations. However, the legal challenges already emerging against similar deportations to Eswatini suggest this approach will face significant scrutiny in the courts. For Garcia himself, the future remains uncertain as he potentially faces relocation to a country thousands of miles from his homeland, with a vastly different culture, language, and social structure. His case exemplifies the human impact of evolving immigration policies and raises profound questions about the balance between national security concerns and the rights of even those accused of serious crimes.