Judge Blocks DOJ Access to Evidence in Potential Comey Prosecution Case

In a significant legal development, a federal judge in Washington, DC has temporarily restricted the Department of Justice from using certain evidence linked to Daniel Richman, a law professor and former attorney for ex-FBI Director James Comey. Judge Colleen Kollar-Kotelly’s ruling represents a setback for prosecutors who are considering renewing charges against Comey following a previously dismissed criminal case. This judicial intervention highlights the complex intersection of constitutional rights, prosecutorial authority, and the lingering political tensions surrounding investigations related to the 2016 presidential election.

The court’s decision specifically addresses materials seized from Richman’s electronic devices during investigations conducted in 2019 and 2020. Judge Kollar-Kotelly determined that Richman “is likely to succeed on the merits of his claim that the government has violated his Fourth Amendment right” by keeping and searching a complete copy of files from his personal computer without a warrant. The ruling orders the Justice Department to “identify, segregate, and secure” these materials and prohibits their access without court approval. This temporary restraining order aims to maintain the status quo while the court fully evaluates Richman’s motion for the return of his property, with the judge noting that the facts “weigh in favor of entering a prompt, temporary order” even before the government files its formal response.

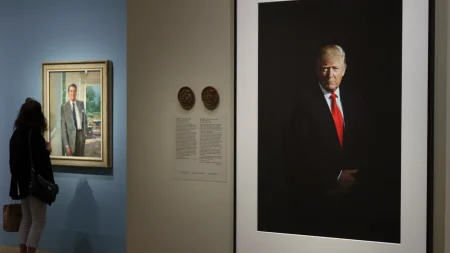

The significance of this ruling becomes clear when considering the broader context of the DOJ’s efforts against Comey. Prosecutors had previously used files obtained from Richman’s devices to indict the former FBI director on charges of making false statements and obstructing Congress regarding his 2020 testimony about FBI officials anonymously providing information to news outlets. The indictment specifically implicated Richman, who had served as a special FBI employee, alleging he communicated with reporters about investigations into Hillary Clinton during the contentious 2016 presidential election that resulted in Donald Trump’s victory. The evidence in question thus forms a crucial link in the government’s case against Comey, making this temporary restriction potentially consequential for any renewed prosecution efforts.

The timing of this judicial intervention is particularly notable as it comes while the Justice Department contemplates whether to pursue another indictment against Comey. The original case against the former FBI director was dismissed last month when another judge determined that lead prosecutor Lindsey Halligan had been unlawfully appointed. This procedural setback forced the DOJ to reconsider its approach, and Judge Kollar-Kotelly’s current ruling adds another layer of complexity to their deliberations. The temporary restraining order remains in effect through December 12 or until further court action, creating a defined timeline during which the DOJ must navigate these new restrictions as they decide whether to proceed with charges against Comey.

This legal battle reflects the continuing reverberations of the politically charged 2016 election period and its aftermath. Comey’s handling of investigations related to Hillary Clinton’s emails and possible Russian interference became extraordinarily controversial, with his decisions drawing criticism from across the political spectrum. The potential prosecution of Comey, who was fired by President Trump in 2017, touches on fundamental questions about accountability, the proper role of law enforcement in politically sensitive investigations, and the boundaries between legitimate prosecutorial discretion and potential political motivation. Richman’s involvement adds another dimension, as he became a significant figure when Comey acknowledged sharing memos about his interactions with President Trump through Richman to the press.

The case also underscores broader tensions regarding Fourth Amendment protections in the digital age. Richman’s challenge to the government’s retention and searching of his electronic files without a warrant raises important questions about privacy rights and proper procedures when law enforcement seizes digital information. As the courts continue to develop precedents in this area, Judge Kollar-Kotelly’s ruling suggests a judicial willingness to carefully scrutinize government handling of seized electronic data, particularly when it may be used in high-profile prosecutions with political implications. While temporary in nature, this restraining order represents an important assertion of judicial oversight in an area where technological advances have sometimes outpaced legal frameworks, creating new challenges for balancing effective law enforcement with constitutional protections.