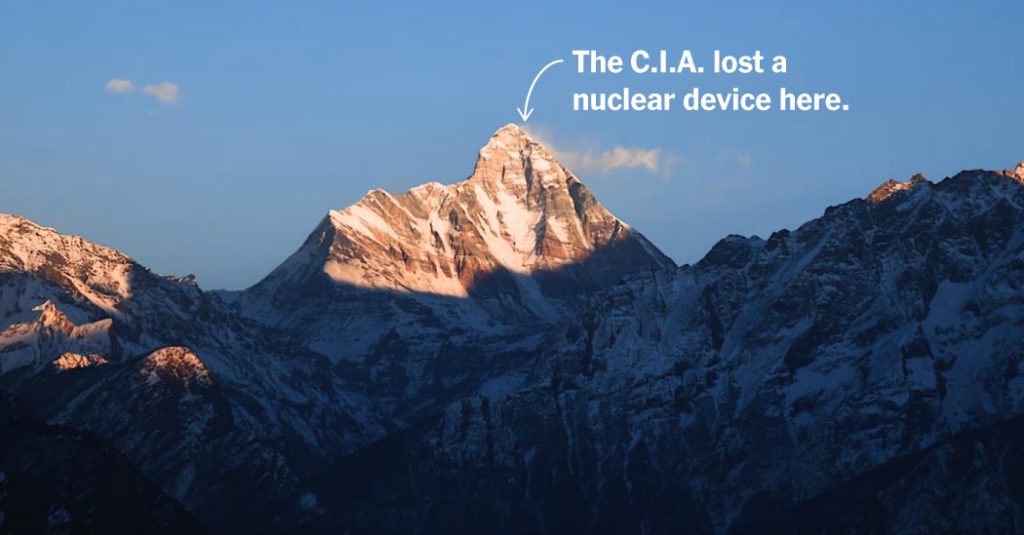

The Lost Nuclear Device of Nanda Devi: America’s Secret Himalayan Mission

Cold War Espionage Leaves Dangerous Legacy in the World’s Highest Mountains

In the shadowy landscape of Cold War espionage, few operations match the audacity—and ultimate failure—of a classified 1965 mission that sent American climbers to the roof of the world. Handpicked by the CIA for both their mountaineering prowess and discretion, these men were tasked with installing a nuclear-powered surveillance device atop one of the Himalayas’ most forbidding peaks. More than half a century later, the radioactive device they abandoned remains missing, its potential dangers unresolved, and the full story of what happened on that mountain continues to haunt those involved.

“I’ll never forget the moment Kohli left it up there,” recalls Jim McCarthy, now 92 and the last surviving American climber from the mission. “I had this flash of intuition we’d lose it. I told him, ‘You’re making a huge mistake. This is going to go very badly. You have to bring that generator down.'”

That generator—containing plutonium with nearly a third of the radioactive material used in the Nagasaki bomb—has never been seen since.

The Genesis of Operation “Nanda Devi”

The mission was born out of Cold War paranoia and geopolitical necessity. In October 1964, China detonated its first atomic bomb in the Xinjiang region, sending shockwaves through Washington. President Lyndon B. Johnson and his intelligence apparatus were desperate to monitor China’s emerging nuclear capabilities, but they faced significant challenges in gathering intelligence from inside the secretive nation.

The audacious plan reportedly emerged during a cocktail party conversation between Air Force General Curtis LeMay, a noted Cold War hawk, and Barry Bishop, a National Geographic photographer who had recently summited Mount Everest. As Bishop regaled LeMay with tales of the panoramic views from Everest—and how one could see hundreds of miles into Tibet and China—an idea formed that would eventually lead to one of the CIA’s most unconventional operations.

Soon after, the CIA summoned Bishop and outlined an ambitious scheme: American alpinists would secretly enter the Himalayas, haul surveillance equipment up treacherous slopes, and install a sensor at a mountain summit to intercept radio signals from Chinese missile tests. The device would be powered by a SNAP-19C generator—a portable nuclear power source containing highly radioactive plutonium, similar to those used for deep space exploration.

Bishop, with his National Geographic credentials providing perfect cover for prolonged disappearances to remote locations, became the mission’s civilian organizer. Documents recently discovered in his garage in Montana reveal his meticulous planning: phony business cards, letterhead for the fictional “Sikkim Scientific Expedition,” bank statements, gear lists, and even detailed menu plans down to the chocolate and honey bars the climbers would consume.

The Ascent Begins: American and Indian Climbers Join Forces

The operation relied on unprecedented cooperation between American and Indian intelligence services. While the United States feared China’s nuclear ambitions, India had even more immediate concerns, having suffered a humiliating defeat in a border war with China just three years earlier.

“You see, we had just lost a war to China—no, not just lost, we had been humiliated,” explained R.K. Yadav, a former Indian intelligence officer.

India’s Intelligence Bureau appointed Captain M.S. Kohli, a decorated naval officer and accomplished mountaineer who had recently led the first successful Indian expedition to Everest, to head the Indian contingent. The Americans recruited Jim McCarthy, an elite rock climber who had graced the cover of Sports Illustrated in 1958, among other skilled alpinists who could be trusted with state secrets.

The initial CIA proposal targeted Kanchenjunga, the world’s third-highest mountain, but both McCarthy and Kohli immediately rejected this as impractical. “I told them whoever is advising the CIA is a stupid man,” Kohli later recounted. “I told them it would be, if not impossible, extremely difficult.” Instead, the 25,645-foot Nanda Devi was selected—a mythic peak ringed by white-toothed mountains that Hugh Ruttledge, a famous pre-war British mountaineer, had described as harder to reach than the North Pole.

In mid-September 1965, the American climbers arrived in New Delhi under the cloak of secrecy. After a brief helicopter ride to the foot of Nanda Devi, around 15,000 feet above sea level, the team began their ascent. Battling altitude sickness, extreme cold, and treacherous conditions, the climbers and their Sherpa porters established a series of camps along the ridgeline that gradually narrowed to a knife’s edge.

Oddly enough, the radioactive material became a source of comfort in the bitter mountain environment. The plutonium-238 in the device generated heat due to its relatively short 88-year half-life. “The Sherpas loved them,” McCarthy remembered. “They put them in their tents. They snuggled up next to them.” Captain Kohli later noted with regret that “the Sherpas called the device Guru Rinpoche [the name of a Buddhist saint] because it was so warm,” adding grimly, “At the time, we had no idea about the danger.”

Disaster Strikes: The Abandoned Device

By mid-October, the mission was faltering. Handwritten notes in Bishop’s files chronicle the deteriorating situation: “High winds.” “Tent was lost.” “Short of food.” “Snows all day.” “Very discouraging evening.”

On October 16, as the team attempted to push for the summit, disaster struck. A blizzard engulfed the mountain, trapping several climbers high on the peak. “We were 99 percent dead,” remembered Sonam Wangyal, an Indian intelligence operative and experienced mountaineer who was near the summit. “We had empty stomachs, no water, no food, and we were totally exhausted. The snow was up to our thighs. It was falling so hard, we couldn’t see the man next to us, or the ropes.”

Captain Kohli, monitoring the situation from advance base camp, made the fateful decision that would haunt him for the rest of his life. Over the crackling radio, he ordered the climbers to abandon the nuclear device at Camp Four and descend immediately. “Secure the equipment. Don’t bring it down,” he instructed them.

McCarthy, who had just descended from a supply run to a lower camp, was furious when he overheard Kohli’s instructions. “You have to bring that generator down!” he shouted. But with the operation taking place on Indian soil, the Americans had no authority to countermand Kohli’s orders. The climbers stashed the nuclear device on a ledge of ice and rock, securing it with metal stakes and nylon rope before hurrying down the mountain to safety.

The team planned to return the following spring when weather conditions improved. But when they returned to Camp Four in May 1966, they found nothing. A winter avalanche had sheared away the entire ledge where the equipment had been secured. The nuclear device, with its seven tubular plutonium fuel capsules, had vanished into the vast white wilderness of the Himalayas.

A Secret Unravels: The Public Discovery

The mission remained classified for more than a decade, and might have stayed that way if not for the persistence of Howard Kohn, a journalist who had previously broken major stories for Rolling Stone. Through connections on Capitol Hill and interviews with bitter climbers from the expedition, Kohn uncovered the story and published “The Nanda Devi Caper” in Outside magazine on April 12, 1978.

The revelation caused an international uproar. In India, protesters took to the streets with signs reading “CIA is poisoning our waters.” Opposition leaders harassed the prime minister in Parliament, accusing him of collaborating with “the notorious CIA”—a particularly damaging charge for a nation that prided itself on leadership of the non-aligned movement during the Cold War.

The greatest concern centered on the Ganges River. Nanda Devi’s ancient glaciers feed tributaries of India’s most sacred river, which runs more than 1,500 miles and sustains hundreds of millions of people. Could the device contaminate this vital waterway?

Indian Prime Minister Morarji Desai stood before Parliament and assured the nation there was “no cause for alarm.” But to be “triply sure,” he appointed a committee of experts to investigate potential risks to “the waters of our sacred river Ganga.”

Behind the scenes, diplomatic cables reveal that the United States urged India to deny the operation entirely. Desai largely complied, avoiding any mention of the CIA in his public statements. President Jimmy Carter expressed his gratitude in a secret message to Desai dated May 8, 1978: “May I express my admiration and appreciation for the manner in which you handled the Himalayan device problem.”

When the two leaders met in the Oval Office weeks later, Carter told Desai that “he was glad that neither of them had been involved” in the mission, which had occurred years before they took office. Historians note how effectively they collaborated to manage the potential diplomatic crisis.

“This was the kind of thing that you could have made a big deal out of—that the CIA was messing around with plutonium in the Himalayas,” observed Gary Bass, a Princeton historian. “Instead, they both work to hush it up.”

The Ongoing Threat: Environmental and Security Concerns

In February 2021, a massive landslide near Nanda Devi triggered a surge of water, mud, and debris that killed more than 200 people and destroyed a hydroelectric dam. Many locals immediately suspected the missing nuclear device, though scientists later attributed the disaster to climate change causing glacial fractures.

The question remains: How dangerous is the missing device? The Indian government’s 1979 expert committee concluded that even if the generator cracked open and the plutonium capsules were exposed, the risks of radiation poisoning the water supply were “negligibly small.” Modern scientists generally agree, given the enormous volume of water flowing through the Himalayan river system.

However, serious concerns persist. As global warming accelerates and glaciers retreat, objects long buried in ice are increasingly being exposed. The greatest worry is that someone might find the device and not understand its dangers—or worse, that its radioactive materials could be recovered by those with nefarious intentions.

“The biggest danger is a dirty bomb,” explains David Hammer, a professor of nuclear energy engineering at Cornell University. If the generator’s capsules ended up in the wrong hands, they could be used to make a weapon that would spread panic by dispersing radioactive dust over a populated area. The missing plutonium, he notes, represents “quite a lot of material.”

McCarthy believes his testicular cancer diagnosis in 1971 resulted from exposure to the device. “There’s no history of cancer in my family, none, going back generations,” he said. “I have to assume that after loading this goddamn thing, I was exposed.” He claims the engineers misled the team about radiation risks: “They told me it was completely shielded. That thing should have weighed 100 pounds if it were completely shielded. It weighed 50.”

Legacy of a Failed Mission

Today, as India pursues development in the Himalayas—building hydroelectric dams, widening mountain roads, and establishing military outposts along the Chinese border—the lost nuclear device represents an uncomfortable chapter in the nation’s history that refuses to be forgotten.

“The radioactive material is right there, inside the snow,” says Satpal Maharaj, the tourism minister for Uttarakhand state. “Once and for all, this device must be excavated and the fears put to rest.”

In July, Nishikant Dubey, a member of Parliament from Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s party, questioned whether the device might be responsible for a series of natural disasters in the region. “Who owns that device should take out that device,” he insisted.

The American government maintains its decades-long silence. When asked about the mission recently, the State Department offered nearly the identical response it gave in 1978: “As a general practice, we don’t comment on intelligence matters.”

For Captain Kohli, who died in June, the mission represented a painful regret. “I would not have done the mission in the same way,” he reflected in one of his final interviews. “The CIA kept us out of the picture. Their plan was foolish, their actions were foolish, whoever advised them was foolish. And we were caught in that.”

As his gaze drifted past his climbing medals and a painting of a Himalayan peak jutting into a deep blue sky, he concluded: “The whole thing is a sad chapter in my life.”

Six decades after its loss, the nuclear device remains somewhere beneath the ice and rock of one of the world’s most remote regions—a dangerous relic of Cold War ambitions and miscalculations that continues to cast a long shadow over the sacred peaks of the Himalayas.