The Unabomber’s Harvard Experiment: How Unethical Research Potentially Shaped a Criminal Mind

Before Ted Kaczynski became known worldwide as the “Unabomber,” he was just a 16-year-old prodigy who had earned his place at Harvard University in 1958. However, during his time at this prestigious institution, young Kaczynski was selected to participate in a psychological experiment that many experts now question for its potential influence on his later transformation into one of America’s most notorious domestic terrorists. At this formative age, when most teenagers are still developing their sense of self and worldview, Kaczynski became a subject in psychologist Henry A. Murray’s controversial three-year study that probed the depths of the human psyche in ways that would be considered ethically problematic by today’s standards. Dr. Ann Wolbert Burgess, a pioneer of the FBI’s Behavioral Science Unit, reflected on the impact this experience likely had on the impressionable teen, noting, “He was very vulnerable because of his age and all… I think it would affect him. I think it did affect him.”

Murray’s experiment, conducted during the Cold War era when psychological research was intensely focused on potential national security applications, began innocently enough. Twenty-two Harvard students, including Kaczynski, were asked to write comprehensive essays detailing their personal philosophies and worldviews. However, what followed crossed boundaries that modern research ethics would never permit. After submitting their deeply personal essays, the students were wired to electrodes, seated under harsh lighting, and subjected to what Murray himself described as “vehement, sweeping, and personally abusive” interrogations designed to attack and undermine their most cherished beliefs. The students had not been fully informed about the true nature of the experiment – that they were essentially test subjects for developing interrogation techniques that could be used by government agents and law enforcement officials. This deception violated a fundamental principle of ethical research: informed consent.

The psychological impact of such treatment on a 16-year-old boy cannot be overstated. As Dr. Burgess explained, the timing of this experiment coincided with a critical developmental period in Kaczynski’s life: “Their whole being, at that particular point in their development, is academics and knowledge. They were being demeaned for that, or devalued for that in this critical time.” While Murray’s research did not technically violate the ethical guidelines of that era – it fell under the non-legally binding Nuremberg Code established after World War II – Dr. Burgess maintains that the experiment was inherently harmful. “You’re not there to injure,” she emphasized, “and certainly what Murray and his crew were doing was injurious.” The practice of hooking participants to electrodes while subjecting them to personal attacks violated modern ethical principles that require research to avoid harm and to provide some form of compensation or benefit to participants.

As investigators pieced together Kaczynski’s life following his arrest, the revelations about Murray’s experiments cast a shadow over the psychologist’s professional legacy, despite his death in 1988. The question lingered: did this intense psychological experience contribute to Kaczynski’s descent into violence? After his 17-year bombing campaign that killed three people and injured 23 others, Kaczynski was eventually diagnosed with schizophrenia. This mental illness, potentially exacerbated by the psychological trauma he experienced during the Murray experiments, may help explain how a brilliant mathematician transformed into a reclusive terrorist who waged war against modern technology and industrial society. Kaczynski’s defense lawyers reportedly wanted to argue that Murray’s experiments had affected his thinking, and many experts believe there’s merit to this theory, though definitive proof remains elusive.

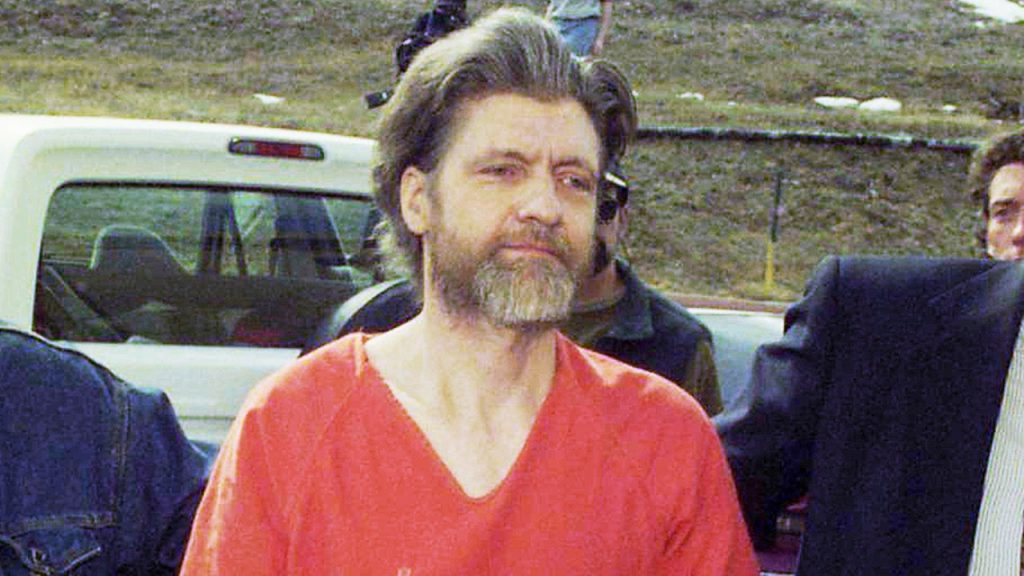

In 1998, Kaczynski pleaded guilty to charges related to his bombing campaign and was sentenced to life imprisonment. He ultimately died by suicide in 2023 while incarcerated at a federal prison medical center in Butner, North Carolina. His death closed the final chapter on his life but left many questions unanswered about the factors that contributed to his radicalization and violence. Harvard University has remained silent on the matter, declining to comment on this dark chapter in its research history. Meanwhile, despite the controversy surrounding Murray’s methods, elements of his research approach reportedly continue to influence modern psychological examinations, though presumably with greater ethical safeguards.

The case of Ted Kaczynski serves as a haunting reminder of the potential consequences when psychological research crosses ethical boundaries, especially when involving vulnerable subjects. While we cannot definitively state that Murray’s experiments directly caused Kaczynski’s later criminal behavior, the timing and nature of this intense psychological experience during his formative years raise troubling questions about its impact. As Dr. Burgess poignantly noted, “Did any of this affect him? Evidently, his defense lawyers at his trial wanted to make the argument that this did affect his thinking – and it very well could have.” The Unabomber case thus stands as a cautionary tale about the profound responsibility researchers bear when probing the human mind and the lasting damage that can occur when that responsibility is not fully honored.