For much of the post-Cold War era, Europe lived under the illusion that peace was a permanent condition. Budgets once set aside for defense were joyfully redirected into social programs—healthcare, pensions, housing subsidies—anchored in a hopeful outlook that the days of large-scale land wars were behind us. NATO, buoyed by America’s vast military expenditures, acted as the continent’s safety net, ensuring collective security even as European defense spending dwindled. But that optimism has all but vanished. Today, Europe finds itself grappling with anxieties spawned from an ongoing war in Ukraine, a resurgent Russia, and the prospect of a familiar—but starkly isolationist—Donald Trump returning to the White House.

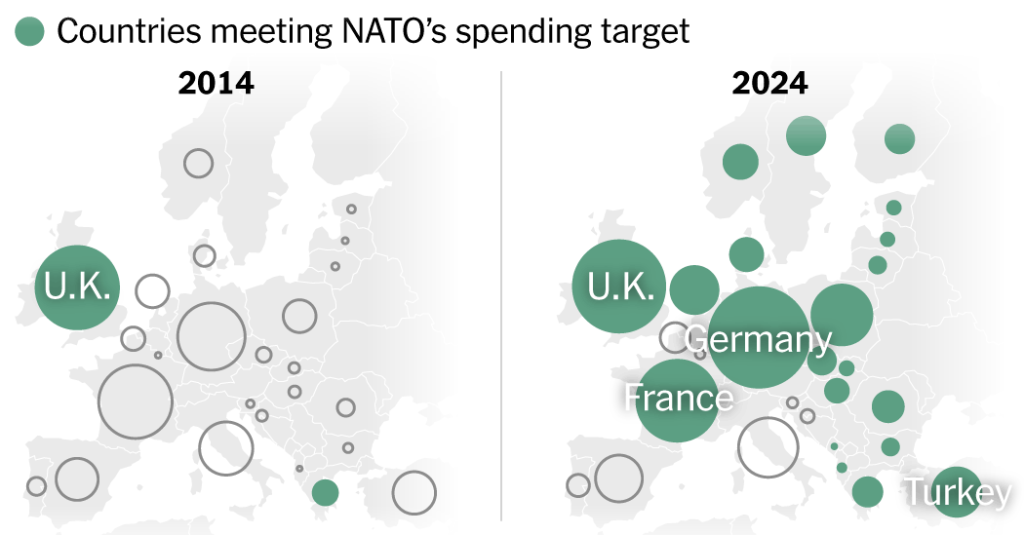

The decades-long stagnation or reduction in European defense spending left militaries on the continent unprepared for a major conflict. Their equipment is outdated, forces are undersized, and operational independence from the United States seems a distant dream. Back in 2014, when Russia annexed Crimea, NATO members formally agreed to allocate at least 2% of GDP to military expenses, a target that had lingered on the fringes of policy discussions for years. Yet, with 2024 now underway, eight NATO countries remain below that threshold, and many experts argue that 2% is no longer sufficient. While European leaders debate how to ramp up spending, former U.S. President Trump has reignited pressure for radical increases, proposing NATO members hike their military budgets to an eye-watering 5% of GDP—more than twice the current target and surpassing America’s own defense spending relative to its economy.

But Trump isn’t the only voice pushing for higher military budgets. Germany’s economic minister, Robert Habeck, recently floated the idea of raising his country’s defense spending to 3.5% of GDP, arguing that “we need to spend almost twice as much on defense so that Putin does not dare to attack us.” On Europe’s eastern flank, where the proximity to Moscow’s aggression feels like an ever-present danger, nations like Poland have already raised their defense spending dramatically, allocating 4% of GDP to their military budget in 2024, the highest ratio in NATO. For countries farther from Russia’s reach, like Spain and Italy, the pace of change has been notably slower. Both devote less than 1.5% of their GDP to defense—a stark contrast to their swelling budgets for pensions and healthcare, driven largely by aging populations.

Yet analysts warn that even countries currently posting higher numbers have been playing catch-up rather than growing genuinely robust armies. For much of the last thirty years, European defense strategies revolved around assumptions that future wars would be short, surgical, and technologically driven. This led to investments in high-precision weapons and specialized forces but not the tanks, long-range missiles, or expansive logistical capacities required for drawn-out conflicts like the one unfolding in Ukraine. Decades of underfunding—and wrongly betting on the nature of future warfare—left Europe ill-equipped for the modern realities of sustained, large-scale ground combat.

Sean Monaghan, a strategist with the Center for Strategic and International Studies, points out that much of Europe’s current military spending is going toward replacing weapons and equipment sent to Ukraine or catching up on basic deficiencies in its aging inventories. As alarming as the rhetoric about higher defense goals may sound, Monaghan suggests that Europe remains far from developing the kind of military capacity required to confront a major nuclear power like Russia on its own. “It’s not substantially increasing Europe’s defense capabilities in a way that would enable it to succeed in a war against Russia,” he observes.

The backdrop for this renewed urgency in Europe’s military discourse is a fundamental shift in U.S.-European dynamics within NATO. Historically, the United States has bankrolled roughly two-thirds of NATO’s military budget. For decades, European countries leaned on this American commitment, holding fast to NATO’s principle that an attack on one member would be treated as an attack on all. That sense of security allowed European nations to limit their defense spending, prioritizing generous social safety nets instead.

But Trump’s previous rhetoric during his presidency already shook those assumptions. He openly expressed disdain for NATO allies who didn’t meet spending targets, often conflating contributions to the NATO budget with bilateral defense capabilities. As his potential return to office looms on the horizon, his criticism has grown harsher. He has suggested allowing Russia free rein with NATO nations that fail to pay what he deems an acceptable share, saying he would encourage them to “do whatever the hell they want” in such cases. His blunt demand that European countries aim for 5% of GDP sends a clear signal: America’s support cannot be taken for granted under his administration.

This growing sentiment of uncertainty has driven many European policymakers to reconsider long-held economic and political trade-offs. Over the past three decades, spending on healthcare, housing, and other social protections steadily grew across Western Europe. Redirecting resources from hospitals or pensions to tanks and aircraft carriers reveals the kind of existential trade-offs countries are now weighing. As Daniel Fiott of the Brussels School of Governance notes, the 2% spending goal once seen as a ceiling is increasingly viewed as a baseline. However, this pivot comes with challenges. Spending beyond the current benchmarks could mean significant adjustments to other budget priorities, particularly for nations with already strained public finances.

Some countries have less flexibility to navigate these changes. Spain and Italy, for example, have ballooning expenses tied to aging demographics, further complicating efforts to reallocate funding for defense. A European-wide shift toward higher military budgets also faces structural hurdles. Unlike the United States, which benefits from economies of scale by drawing funding into centralized defense projects, Europe’s patchwork of national militaries drives inefficiencies. Countries often prioritize funneling contracts to their domestic defense industries, leading to overlapping efforts and redundant costs rather than cohesive capabilities.

And while certain militaries invest in growth, others are already eyeing an exit ramp. German Economic Minister Robert Habeck suggested that if Germany commits to higher spending in the short term, it could reduce the defense target once it achieves a “reasonable state” of security. Analysts like Monaghan call such intentions “wishful thinking,” emphasizing that the current aggression from Russia is unlikely to dissipate soon. “The constant threat from Russia is the new normal, and we need to prepare for that and invest in our defense for that,” he cautions.

Meanwhile, Vladimir Putin’s Russia, unrestrained by the same internal debates that preoccupy European policymakers, has ramped up its military spending to 6.3% of GDP. This starkly contrasts with Europe, where leaders are fiercely protective of expansive social programs. Despite the war on NATO’s eastern doorstep, the path to significantly increasing defense spending remains fraught, with few nations eager to embrace politically painful measures such as higher taxes or reductions in social safety nets.

All of this underscores an existential question for post-Cold War Europe: Can it adapt its priorities to address the new geopolitical reality of a perpetually assertive Russia and an increasingly unreliable America? So far, there’s little consensus on how that transformation should unfold—if at all. While some imagine a future of peace and reduced spending after meeting short-term needs, experts caution against prematurely scaling back. If Europe is to secure long-term safety and stability, it must confront difficult and often uncomfortable decisions about its collective approach to defense. Ultimately, the integration of robust military capability into Europe’s budgetary ecosystem requires a political willpower that has yet to fully coalesce. For now, Europe is still struggling to fully come to terms with the stark reality that came rushing in when the illusion of eternal peace crumbled.