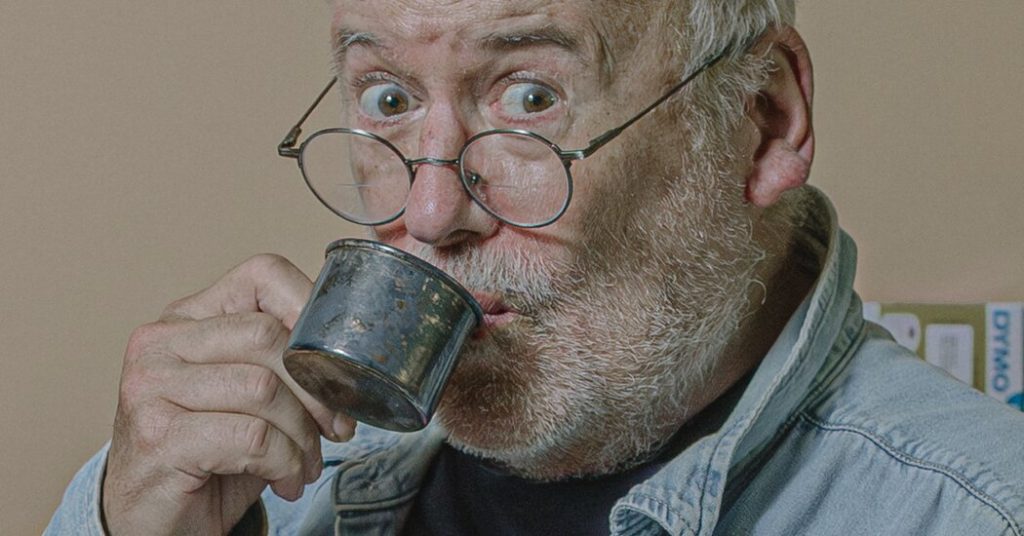

Robert Munsch: A Storyteller’s Twilight

In a quiet moment of unexpected creativity, children’s author Robert Munsch found one last story bubbling up from his imagination in 2023. Despite living with advancing dementia, Munsch’s thoughts turned to Ruth, a woman in her nineties who lived nearby and had recently been hospitalized. This sparked a whimsical question: “What if she had gone to the hospital when she was 6 years old?” From this simple wondering emerged “Bounce!” – a tale of two young girls, Ruth and Barbara, who are taken to a hospital for a scraped knee, only to find themselves bouncing on a hospital bed, pressing buttons, and eventually getting trapped inside when the bed snaps shut. Over several days, Munsch wrote and refined this story, not before actual children as he had done throughout his career, but before an imaginary audience of youngsters in his mind – calling out, growing restless, interrupting just as real children would. When his editor received the draft, she was astonished. After years without new material, this story had simply “happened,” as Munsch himself put it. Published in 2024, “Bounce!” became his unexpected late-career gift to young readers, alongside “The Perfect Paper Airplane,” an earlier work he recently revised for publication by Scholastic. Since then, the wellspring of new stories has gone quiet.

The silence of Munsch’s creative voice stems from his dementia, but perhaps equally from his separation from the children who were always more than just his audience – they were essential collaborators in his creative process. Throughout his celebrated career, Munsch developed stories by telling them directly to children, watching their reactions, and adapting his narratives based on their engagement. It was a symbiotic relationship that fueled his unique storytelling style. Now, as health limitations keep him largely isolated from these young creative partners, Munsch feels his former self “going further and further away.” The distance grows between the storyteller he was and the man he is becoming – a transformation he observes with remarkable clarity and occasional humor, despite its painful reality. His career, which produced beloved classics like “Love You Forever” and “The Paper Bag Princess,” now exists largely in memory, both for his millions of readers and, increasingly, for Munsch himself.

Munsch now exists in that disquieting space where he remains self-aware enough to witness his own cognitive decline. With characteristic directness, he wonders if in a year he might be “a turnip” – his colorful metaphor for profound cognitive impairment. This awareness brings both blessing and burden; he can still connect with loved ones and appreciate his legacy, yet must face the progressive loss of his abilities with full understanding. Recently, his seven-year-old grandchild asked the difficult questions children often pose with disarming straightforwardness: Was he sick? Would he die? Munsch responded with a simple “Yes,” adhering to his lifelong principle of honesty with children. There’s something profoundly fitting about this exchange – the man who spoke truth to children through stories for decades continues to offer them honesty, even when the truth is difficult. Throughout his career, Munsch never shied away from challenging topics in his children’s books, addressing emotions and situations that many authors might avoid. Now, he brings that same unflinching approach to his own mortality.

With the pragmatism that has characterized much of his life, Munsch has made preparations for his end. Shortly after his diagnosis, he applied for and received approval for medical assistance in dying, an option legalized in Canada in 2016. He approaches even this solemn subject with his trademark humor, joking about greeting the doctor with “Hello, Doc – come kill me!” His decision was influenced by watching his brother, a monk, suffer through a prolonged death from Lou Gehrig’s disease, as those around him advocated for continued medical interventions, believing it aligned with divine will. Munsch’s perspective was different: “Let him die.” This experience solidified his determination to avoid a similar prolonged decline. With characteristic clarity, he has established his own threshold: “When I start having real trouble talking and communicating. Then I’ll know.” Communication – the foundation of his life’s work as a storyteller – remains his benchmark for a life worth living.

The trajectory of Munsch’s life reveals a man whose connection to children has been the consistent thread through personal and professional challenges. Long before dementia, Munsch navigated other difficulties including struggles with addiction and mental health, which he has discussed openly. His honesty about these struggles, like his approach to storytelling, reflected his belief that children deserve authenticity. Munsch’s stories have always occupied that special place where simplicity meets profundity – tales that make children laugh while touching on deeper truths about emotions, relationships, and the human experience. His work resonated because it acknowledged children as complete human beings with complex inner lives, not merely as simplified creatures requiring watered-down content. This respect for children’s emotional intelligence became his hallmark, creating stories that children requested again and again, and that parents found themselves reciting from memory after countless bedtime readings.

As Munsch faces the final chapter of his own story, there’s a poetic resonance to how his approach to storytelling parallels his approach to living and dying. Throughout his career, he trusted children with difficult emotions, with understanding complexity, with facing uncomfortable truths wrapped in humor and humanity. Now, he approaches his own mortality with that same combination of honesty, directness, and occasional laughter. The man who wrote “Love You Forever,” a story that has moved generations of parents to tears as it confronts the cycle of care between generations, now navigates his own place in that cycle with clear-eyed awareness. While dementia progressively claims parts of his identity, the essence of Robert Munsch – his respect for children, his belief in emotional honesty, his ability to find humor in difficult situations – remains visible in how he faces his final journey. For a man who spent his life crafting memorable endings to stories that delighted millions of children, there is dignity in how he contemplates the conclusion of his own remarkable tale.