The Judgment of Reading: One Woman’s 120-Book Triumph Sparks Debate

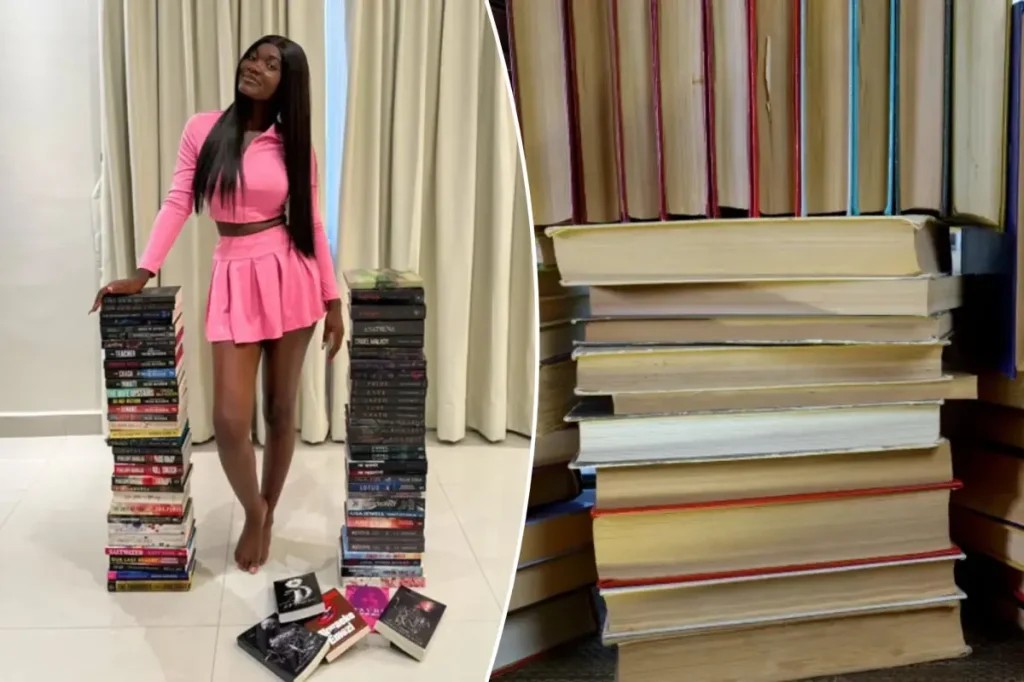

As we approach 2026, many people are crafting New Year’s resolutions, with “read more books” being a popular goal on many lists. While setting ambitious reading targets might seem admirable, one woman’s recent achievement has sparked an unexpected online debate about what “counts” as reading and whether quantity should be celebrated over quality. Digital marketer and book content creator Armah recently shared her triumphant moment on X (formerly Twitter), posting a photo of herself beside two impressive stacks of books with the caption, “I did it!! 120 books read this year.” Her accomplishment quickly went viral, garnering nearly 29 million views and igniting a passionate conversation about reading habits, preferences, and judgments.

Many initial responses celebrated Armah’s dedication to reading in an age when digital distractions often pull us away from books. Supportive commenters acknowledged the difficulty of finishing even a single book in today’s fast-paced world. “That’s pretty good. Any book I try to read, 3 pages in I’m sleeping,” confessed one commenter, while another exclaimed, “Wow, 120 books in a year! That’s seriously impressive. Whether fiction or not, your brain must be doing some serious heavy lifting.” These encouraging reactions highlighted how many people struggle with consistent reading habits despite good intentions, making Armah’s accomplishment seem all the more remarkable to those who battle to finish even a handful of books annually.

However, the congratulatory tone quickly shifted when some users discovered many of Armah’s completed titles were e-books and romance novels with mature content—or what some dismissively labeled as “smut books.” Critics began questioning the legitimacy and value of her reading choices, suggesting that certain genres are somehow less worthy of being counted toward reading goals. “Most fiction is slop. Reading 100 trashy fiction books is the equivalent of watching hours of reality TV. Only truly great fiction should be considered reading,” declared one particularly judgmental response. Another bluntly stated, “I didn’t realize smut counts as books,” revealing a troubling hierarchy that many readers impose on different literary genres and formats.

The criticism extended beyond genre preferences into unsolicited life advice and assumptions about Armah’s character and lifestyle. One particularly presumptuous comment suggested: “There is no flex in proving you read 120 books. Congrats to that, but let’s be honest, are you better than academics/students who spend more than a year reading textbooks, articles, journals, to become experts in their field which obviously adds value to the society? I love to read too but you gotta socialize a little bit. Don’t be this lonely, go out, watch a movie with a friend or two.” Others demanded specific types of reading material: “Hood books don’t count. Where are the self-development books?” These comments revealed more about the critics’ biases than about Armah’s reading habits, suggesting that unless someone reads “important” or “valuable” books, their reading somehow doesn’t count.

The controversy highlights a broader cultural tension around reading in the digital age. At a time when many lament declining reading rates and shortened attention spans, it seems counterproductive to gatekeep what “counts” as legitimate reading. Whether someone chooses romance novels, classic literature, graphic novels, or audiobooks, engaging with stories and ideas through reading represents a conscious choice to step away from endless scrolling and passive content consumption. The judgment cast on Armah’s romance novel choices also reveals persistent biases against genres primarily written by and for women—a form of literary snobbery that has diminished women’s writing throughout history while elevating traditionally masculine genres and themes.

When faced with accusations of exaggeration or dishonesty, Armah responded by sharing a screenshot of her Goodreads account, proving the accuracy of her reading count. This digital validation silenced some critics but couldn’t address the underlying issue: why do we feel entitled to judge others’ reading choices at all? In a world where reading any book requires committing time and attention that could easily go to more passive forms of entertainment, perhaps we should celebrate the act of reading itself rather than policing its forms. As we contemplate our own reading resolutions for the coming year, Armah’s experience serves as a reminder that reading should ultimately be a personal journey—one where enjoyment, curiosity, and personal growth matter far more than arbitrary numbers or external validation about what constitutes “worthy” literature.