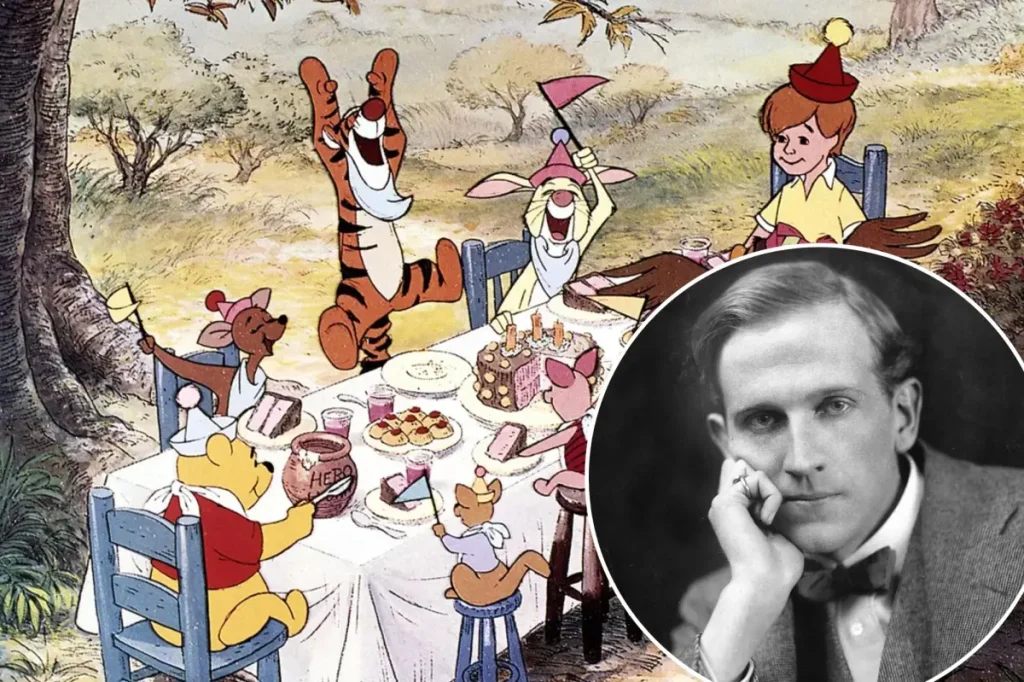

The Man Behind Winnie-the-Pooh: A.A. Milne’s Complex Legacy

Since its publication in 1926, Winnie-the-Pooh has captured the hearts of millions around the world, selling over 50 million copies and becoming one of the most beloved children’s book series of all time. The charming tales of a honey-obsessed bear and his woodland friends in the Hundred Acre Wood have delighted generations of readers. However, as Gyles Brandreth reveals in his book “Somewhere, a Boy and a Bear: A.A. Milne and the Creation of ‘Winnie-the-Pooh’,” the man behind these heartwarming stories led a complex life marked by professional frustration, strained relationships, and the lasting trauma of war. Alan Alexander Milne, despite creating a world of childhood wonder and innocence, was a complicated individual whose personal life often contradicted the simple joy found in his most famous works.

The origin of Winnie-the-Pooh is now the stuff of literary legend. Christopher Robin, A.A. Milne’s only child, received a stuffed bear on his first birthday that the family named Winnie-the-Pooh (after Winnipeg, a popular black bear at London Zoo). Although Christopher was primarily raised by a nanny, he enjoyed special moments with his mother, Dorothy, a wealthy socialite who brought his stuffed animals to life by giving them distinct voices and personalities. His father took notice and began crafting stories around these toys, eventually developing them into the characters readers have cherished for nearly a century. Christopher initially enjoyed the attention that came with being the real-life inspiration for these stories, even recording albums as his fictional counterpart. “Even though I was shy, I think I quite liked the attention,” he later confessed to Brandreth. Yet this blurring of reality and fiction created a confusing childhood experience where the stories became inseparable from their actual lives: “We lived them, thought them, spoke them,” Christopher recalled.

Despite the intimate connection between Milne’s most famous works and his son, their relationship was surprisingly distant. “My father’s heart remained buttoned-up all through his life,” Christopher told Brandreth. “I’m not sure how well I knew him. I’m not sure how well he knew me.” This emotional distance eventually evolved into resentment as Christopher grew older. In his 1974 memoir “The Enchanted Places,” he wrote that it seemed his father “had got to where he was by climbing upon my infant shoulders, that he had filched from me my good name and had left me with nothing but the empty fame of being his son.” This strained relationship worsened when Christopher married his first cousin, which his father strongly disapproved of, driving them further apart. Milne’s difficult personality extended beyond his family – Ernest Shepard, the illustrator of his children’s books, described him as “rather cagey,” while fellow writer P.G. Wodehouse noted Milne’s “curious jealous streak” and admitted he “never liked him much.” Milne’s tendency toward conflict led to estrangements from various family members, including his parents and his brother Barry, with whom he refused to reconcile even as Barry lay dying.

Ironically, the tremendous success of Winnie-the-Pooh became a source of frustration for Milne himself. Before creating his famous bear, he had established himself as a playwright and novelist for adults, writing sophisticated comedies about marriage and relationships, detective mysteries, and psychological portraits of soldiers returning from war. He resented how Pooh overshadowed all his “serious” literary efforts, feeling that critics and readers no longer viewed him as a legitimate author of adult fiction. This professional frustration was compounded by the lasting psychological impact of his service in World War I. Despite being a pacifist at heart, Milne had volunteered for the British Army in 1914, believing it was the “war to end all wars.” His experiences in the Battle of the Somme, where he witnessed fellow soldiers being “blown to pieces,” haunted him for the remainder of his life. “It makes me almost physically sick to think of that nightmare of mental and moral degradation, the war,” he later wrote, revealing how deeply the conflict had affected him.

The later years of Milne’s life were marked by further personal struggles and emotional withdrawal. After his older brother and closest friend Ken died of tuberculosis in 1929, Milne became increasingly isolated and reserved. His marriage also suffered, with both he and his wife engaging in extramarital affairs – she with an American playwright and he with a young actress – though they remained married until his death. Following a stroke in 1952, Milne passed away in 1956 at the age of 74. Christopher attended his father’s funeral but never spoke to his mother again, suggesting that the family rifts continued beyond Milne’s lifetime. The complex relationships within the Milne family stand in stark contrast to the simple, loving friendships portrayed in the Hundred Acre Wood, highlighting the divide between the author’s creative work and personal reality.

By the 1980s, when Christopher Robin Milne spoke with Brandreth, he had made peace with his complicated legacy as the inspiration for one of literature’s most famous characters. “I now realize that life is too short for regrets,” he reflected. “Our childhood is whatever our childhood was. It’s made us who we are. We cannot change it… But we can visit and revisit the best of it whenever we want. And be grateful.” This sentiment echoes the enduring wisdom found in Winnie-the-Pooh itself – that despite life’s complexities and disappointments, there remains value in appreciating simple joys and cherishing fond memories. Perhaps this is the most profound legacy of A.A. Milne’s work: that even a man who struggled with personal relationships and professional dissatisfaction could create stories that continue to offer comfort, wisdom, and delight to readers of all ages. The tales of Pooh, Piglet, Eeyore, and their friends endure not because their creator led an exemplary life, but because they speak to universal truths about friendship, adventure, and the endearing innocence of childhood that resonate across generations.