The narrative of space exploration, often dominated by figures like Glenn, Armstrong, and Aldrin, is far more intricate and surprising than commonly perceived. While these individuals were undoubtedly crucial in shaping the public image of space travel, their triumphs were built upon the foundations laid by less celebrated, and sometimes controversial, pioneers. One such figure is Wernher von Braun, a Nazi scientist who played a pivotal role in the development of the V-2 rocket, the world’s first long-range guided ballistic missile. Captured by American forces at the close of World War II, von Braun’s expertise proved invaluable to the nascent American space program, despite the ethical implications of embracing a former SS officer. His contributions were instrumental in launching America’s first satellite and designing the Saturn V rocket that propelled astronauts to the moon. This decision, though morally complex, underscores the pragmatic approach adopted by the United States in its pursuit of space dominance.

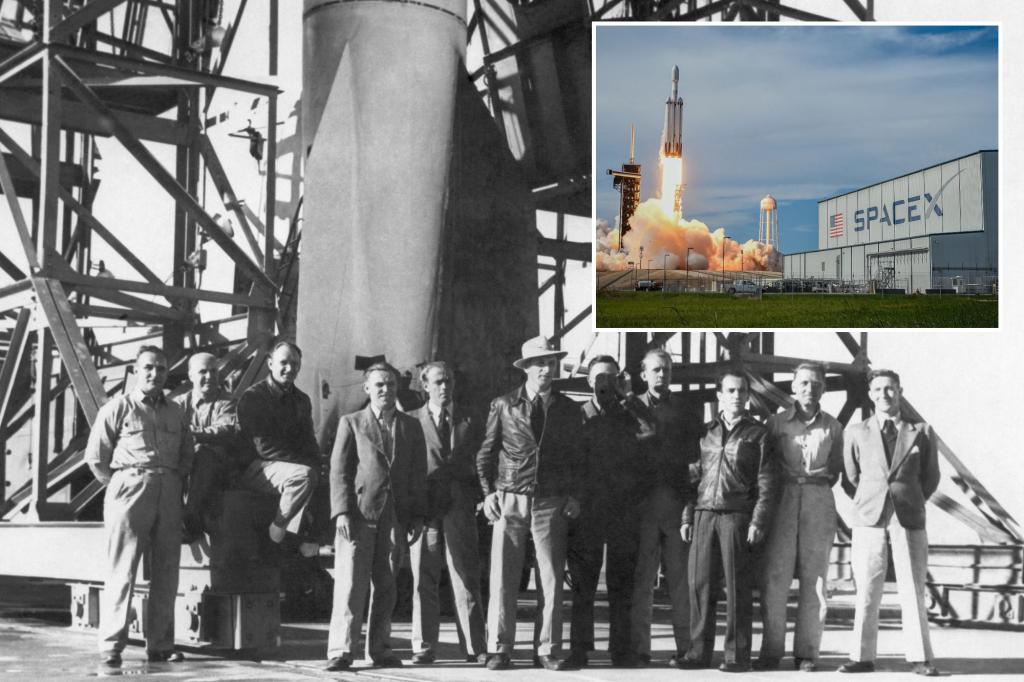

Von Braun’s recruitment was part of Operation Paperclip, a clandestine program that brought over 1,600 German scientists, engineers, and technicians to the United States after the war. These individuals, many with ties to the Nazi regime, possessed specialized knowledge crucial for advancing American rocketry. Among them were Kurt Debus, Arthur Rudolph, and Hubertus Strughold, who contributed significantly to launch operations, Saturn V development, and space medicine, respectively. Their involvement highlights the complicated moral calculus of the Cold War era, as the United States prioritized scientific advancement, often overlooking the past affiliations of these individuals. The integration of these German scientists into the American space program, while ethically questionable, undoubtedly accelerated its progress, transforming former enemies into key contributors to a national endeavor.

However, the narrative of American space exploration extends beyond the contributions of reformed Nazis. Concurrent with the influx of German expertise, homegrown talent was also making significant strides. At the California Institute of Technology, a group of engineers known as the “Suicide Squad,” due to their risky and often explosive experiments, was pushing the boundaries of rocketry. Led by Frank Malina, and including Jack Parsons and Ed Forman, this team developed liquid-fueled launch vehicles, laying the groundwork for what would eventually become the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), a cornerstone of NASA’s deep space exploration program. Their unconventional methods and dedication, despite facing scrutiny from the FBI for their personal lives and political leanings, demonstrate the diverse and sometimes eccentric nature of the individuals who propelled America’s space ambitions.

The combined efforts of these disparate groups – reformed Nazi scientists and American pioneers – culminated in the historic moon landing in 1969. This monumental achievement, a symbol of national pride and technological prowess, marked a turning point in human history. Yet, the momentum of the Apollo program eventually waned, and the late 1970s witnessed a lull in crewed spaceflights. However, the seeds of a new era in space exploration were being sown, driven not by government agencies, but by private individuals with a vision for a future beyond Earth. This shift towards private enterprise marked a paradigm shift in the landscape of space travel, paving the way for commercial ventures that would challenge the traditional dominance of government-led programs.

The resurgence of interest in space exploration was ignited by individuals like David Hannah, a Houston real estate investor inspired by the ideas of physicist Gerard K. O’Neill. O’Neill’s vision of space colonization, driven by the need to address Earth’s dwindling resources, resonated with Hannah, who founded Space Services, Inc. of America (SSIA). In 1982, SSIA launched the Conestoga 1, becoming the first private company to successfully launch a rocket into space. This pioneering achievement, often referred to as the “Kitty Hawk of the commercial space industry,” signaled a new era of private sector involvement in space, demonstrating the potential for commercial ventures to contribute significantly to space exploration. This landmark event laid the foundation for the emergence of private space companies that would redefine the possibilities of space travel in the decades to come.

The transition to private space exploration gained further momentum with the support of the Bush and Obama administrations, which fostered the growth of commercial space ventures through milestone-based contracts. This policy shift opened the door for entrepreneurs like Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos to invest heavily in space technology, developing innovative rockets and spacecraft. Their endeavors, fueled by both ambition and financial resources, have propelled space exploration into a new era, marked by reusable rockets, ambitious plans for Mars colonization, and the increasing accessibility of space travel for private citizens. This privatization of space, while raising new questions about regulation and access, has injected a dynamism and entrepreneurial spirit into the field, pushing the boundaries of what is possible and democratizing access to the cosmos. The question now is not whether humanity will continue to explore space, but rather how this exploration will unfold and what role private enterprise will play in shaping its future.