The Evolving Opera Landscape: Challenges and Opportunities

In a stunning revelation that sent shockwaves through the opera world, renowned tenor Jonas Kaufmann recently announced he would no longer perform at London’s Royal Opera House due to inadequate compensation. “I don’t know how you do it,” he confessed during a BBC Radio 3 interview, where he also declared he would cease appearances at New York’s Metropolitan Opera due to ideological differences. For someone of Kaufmann’s stature—arguably opera’s biggest star—to abandon two of the world’s most prestigious venues is nothing short of cataclysmic. His lament for the next generation of performers underscores a profound crisis in the opera industry. This revelation forces a painful recognition that even at the pinnacle of operatic success, the fundamental challenges of the profession remain unresolved. The romantic notion that reaching the top tier would make the sacrifices worthwhile—the missed holidays, constant travel, vocal health concerns, and emotional toll of rejection—now appears increasingly hollow.

The current state of crisis shouldn’t surprise keen observers of the art form. Stage director Yuval Sharon’s assessment that opera “demands death in order to fulfill its true imperative: to be reborn” captures the existential crossroads facing the industry. In her incisive new book “Opera Wars,” librettist Caitlin Vincent argues that “opera needs to be saved from itself.” The fundamental business model of opera companies has remained largely unchanged since World War II and barely qualifies as a business at all—as one singer aptly noted, “Businesses make money.” The stark reality is that opera has become almost entirely dependent on donations, with even top companies generating only 20-40% of their budgets from ticket sales, while most fall significantly below that threshold. Vincent identifies several contributing factors to this financial predicament, including conflicts between singers and conductors, battles between traditionalists and progressivists, and tensions between outdated cultural representations and evolving societal sensibilities in an increasingly race-conscious and politically polarized environment.

While many regard opera as a static museum piece, Vincent challenges this perception by noting that even Mozart modified “The Marriage of Figaro” between its premiere and subsequent performances. This historical precedent raises important questions about the almost religious reverence modern companies show toward musical scores. The rigid adherence to tradition, often attributed to German influence, may be stifling innovation. However, Vincent cautions against radical reinterpretations that fundamentally alter the essence of classic works. She critically examines the 2018 Maggio Musicale Fiorentino production of “Carmen” that reversed the tragic ending, having the title character kill Don Jose rather than becoming his victim. Though this controversial staging sold out, Vincent dismisses such extreme revisions as ineffective solutions to opera’s troubling audience retention problem, with 80-85% of first-time operagoers never returning for a second performance. The average audience member likely cares less about musical nuances like optional high notes and more about the overall experience, staging, and cultural relevance.

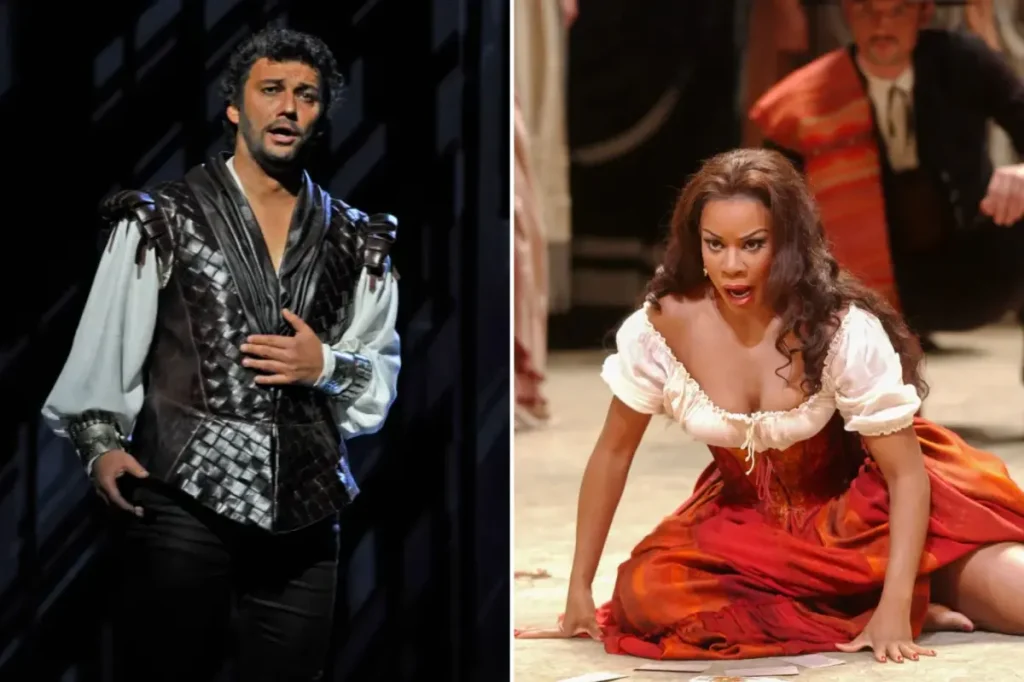

The portrayal of non-Western cultures and characters presents another significant challenge for modern opera companies. Vincent approaches this contentious issue with remarkable balance, drawing on interviews with Black and Asian artists who often feel pigeonholed into roles corresponding to their ethnic backgrounds. Companies struggle to honor both the original material and contemporary sensibilities, sometimes with questionable results. One Korean American performer recounted a production of “The King and I” that cast almost exclusively Asian performers, yet not a single cast member was actually Thai—the nationality depicted in the story. This example highlights the complexity of addressing racial representation in opera. As George Shirley, the first African American tenor to sing a leading role at the Metropolitan Opera, eloquently stated: “You don’t have to be Ethiopian to sing ‘Aida,’ or Japanese to sing ‘Madama Butterfly.’ We see or hear something for which we have an affinity and we are drawn to it, no matter its origin.” Ultimately, these casting debates, regardless of which philosophy companies adopt, may amount to rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic as opera faces more existential threats.

Opera’s greatest battle remains establishing its cultural relevance in contemporary society. Attempts to chase social media trends or political moments have yielded minimal success, largely due to the industry’s glacial planning timeline, with seasons and casting often arranged years in advance. By the time a “timely” production premieres, the cultural moment it aimed to capture has typically passed. Metropolitan Opera bass John Relyea laments the disappearance of the special significance that once accompanied being present at historic performances: “It used to mean something that you were there… That’s almost gone now.” Where Vincent’s analysis shines brightest is in her passionate advocacy for new operas. As a librettist herself, she champions the creation of contemporary works, suggesting that a blend of new pieces alongside traditional favorites represents the most promising path forward. However, the opera industry must first address fundamental accessibility issues, eliminating what Sharon describes as the “barely decipherable ceremony” that alienates newcomers who feel uninitiated into proper opera etiquette. Unlike Broadway shows or foreign-language films, opera continues to struggle with explaining basic attendance protocols and appropriate attire.

In our current era dominated by digital technology and artificial intelligence, opera possesses a unique opportunity to position itself as the ultimate authentic human experience: unamplified voices achieving extraordinary feats without technological enhancement. This distinctive quality could serve as opera’s most compelling selling point to our smartphone-dependent society—if only the industry could effectively market this message. As performing baritone Gideon Dabi concludes, this represents “a war worth fighting.” Opera stands at a crucial crossroads, facing challenges of financial sustainability, cultural relevance, and accessibility. Yet within these challenges lie opportunities for meaningful innovation that honors the art form’s rich traditions while embracing necessary evolution. By addressing these fundamental issues with creativity and courage, opera may indeed experience the rebirth that Sharon envisioned—not as a relic of the past, but as a vibrant, relevant, and deeply human art form for generations to come.