The Breakfast Connection: How Meal Timing Affects Aging and Health

For older adults, the timing of breakfast might matter more than previously thought. According to groundbreaking research from Mass General Brigham, eating breakfast later in the day could be linked to a host of health concerns including depression, fatigue, oral health problems, and even a slightly higher risk of early death. This significant finding suggests that something as simple as when we eat our morning meal could serve as an important indicator of overall health in our later years. “Our research suggests that changes in when older adults eat, especially the timing of breakfast, could serve as an easy-to-monitor marker of their overall health status,” explains lead study author Hassan Dashti, who works as both a nutrition scientist and circadian biologist at Massachusetts General Hospital. The implications of this research could transform how we view daily routines as we age.

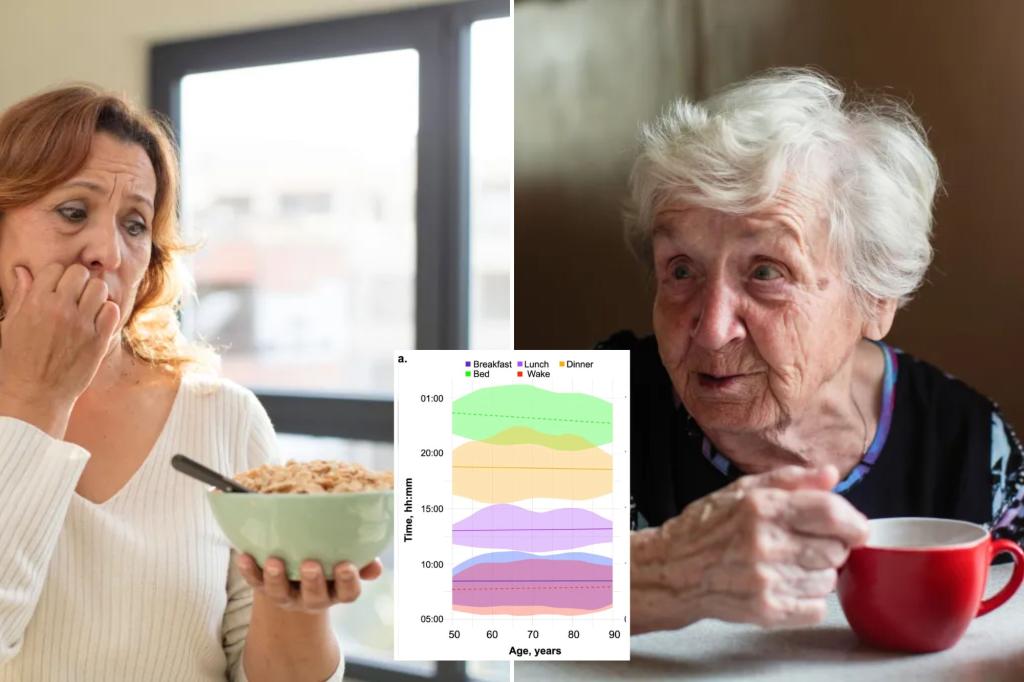

The comprehensive study analyzed data from nearly 3,000 UK residents with an average age of 64, tracking their habits and health outcomes over more than two decades. Researchers collected blood samples and detailed information about participants’ meal and sleep patterns, allowing them to calculate important time intervals: from waking to breakfast, from dinner to bedtime, and between breakfast and dinner. On average, participants ate breakfast about thirty minutes after getting up and had dinner approximately five hours before going to bed. The typical meal schedule showed breakfast at 8:22 a.m., lunch at 12:38 p.m., and dinner at 5:51 p.m. This baseline helped researchers identify shifts in eating patterns as participants aged, revealing that each additional decade of life typically led to progressively later breakfast and dinner times, even if only by a few minutes.

The findings revealed a concerning pattern: “We found that as people aged, they tended to eat breakfast and dinner later, and those with more health problems or a genetic tendency to stay up late also tended to eat later,” the researchers noted in their publication in Communications Medicine. This observation aligns with previous research demonstrating that consistently eating later can disrupt the body’s natural 24-hour biological clock, potentially causing blood sugar spikes and elevated stress hormone levels. Perhaps most striking was the mortality difference between early and late eaters. During the follow-up period, over 2,300 deaths occurred among participants, with researchers calculating that the late-eating group had 10-year survival rates of 86.7% compared to 89.5% in the early-eating group. While this difference might seem modest, it represents a meaningful distinction when considering population-level health outcomes.

The relationship between late eating and health problems appears to be complex and potentially cyclical. Those who struggled with adequate sleep and meal preparation often fell into the late-eating category, suggesting that delayed mealtimes might be both a cause and consequence of other health challenges. “Patients and clinicians can possibly use shifts in mealtime routines as an early warning sign to look into underlying physical and mental health issues,” Dashti explained. This perspective opens up new possibilities for preventive healthcare approaches, where simple lifestyle patterns could serve as early indicators of developing health concerns. The research team suggests that “encouraging older adults in having consistent meal schedules could become part of broader strategies to promoting healthy aging and longevity,” offering a relatively straightforward intervention that might yield significant health benefits.

While the study provides valuable insights, the researchers acknowledge certain limitations that warrant consideration. Their data collection didn’t capture participants’ snacking habits outside of traditional meal times, nor did it measure levels of physical activity, which could influence both meal timing and health outcomes. Additionally, the study population consisted primarily of unemployed women, potentially limiting how broadly the conclusions can be applied across more diverse populations with different lifestyle patterns and socioeconomic circumstances. These limitations highlight the need for further research to explore these relationships across different demographic groups and to investigate potential mechanisms behind the observed associations.

Despite these limitations, Dashti emphasized that the findings help fill an important “gap by showing that later meal timing, especially delayed breakfast, is tied to both health challenges and increased mortality risk in older adults.” The study adds new significance to the age-old wisdom that “breakfast is the most important meal of the day,” particularly for older individuals. As our global population continues to age, understanding how daily routines like meal timing impact health becomes increasingly important. This research suggests that something as simple as maintaining consistent, earlier mealtimes might contribute to healthier aging. For older adults and their caregivers, paying attention to when meals are consumed—not just what’s on the plate—could be a practical way to support overall health and potentially extend lifespan. This perspective transforms breakfast from a mere morning ritual into a potential tool for monitoring and maintaining health as we age.