The Curious Rise of “6-7” Among Today’s Youth: A Blend of Modern Slang and Historical Context

In an unexpected linguistic phenomenon sweeping through schools and playgrounds across America, the seemingly nonsensical phrase “6-7” has become the latest slang obsession among children and teenagers. This peculiar expression, which appears to carry little inherent meaning to most adults, has grown so ubiquitous that it’s driving parents to distraction and even prompting lighthearted interventions from local authorities in some communities.

The fascination with this phrase has reached such proportions that in Tippecanoe County, Indiana, sheriff’s deputies have begun issuing mock “tickets” to children caught using the term excessively. In a tongue-in-cheek social media video, one deputy declared it “against the law to use the words ‘six’ and ‘seven’ unless using them in a math problem or someone’s age.” While clearly meant in good humor, this creative approach highlights just how pervasive the expression has become in youth culture, particularly among elementary school children. The playful citations serve a dual purpose: engaging with young people in a positive way while giving beleaguered parents a moment of respite from the constant repetition of a phrase that seems, to adult ears, completely devoid of substance or utility.

What makes this linguistic trend particularly interesting is the contrast between its apparent meaninglessness in modern usage and its potentially rich historical roots. David Marcus, a columnist for Fox News Digital, stumbled upon this connection after attempting to decipher the expression following his teenager’s use of it. Marcus proposes that “6-7” isn’t a contemporary invention but rather the revival of a much older phrase with legitimate historical significance. According to his research, the expression can be traced back to medieval times and a dice game called Hazard (the predecessor to modern craps). In this gambling context, “six and seven” represented particularly unfavorable outcomes with lower odds of winning compared to more advantageous numbers like five, eight, or nine. Over time, Marcus suggests, “six and seven, taken together, became forever associated with risk and worry” in common parlance.

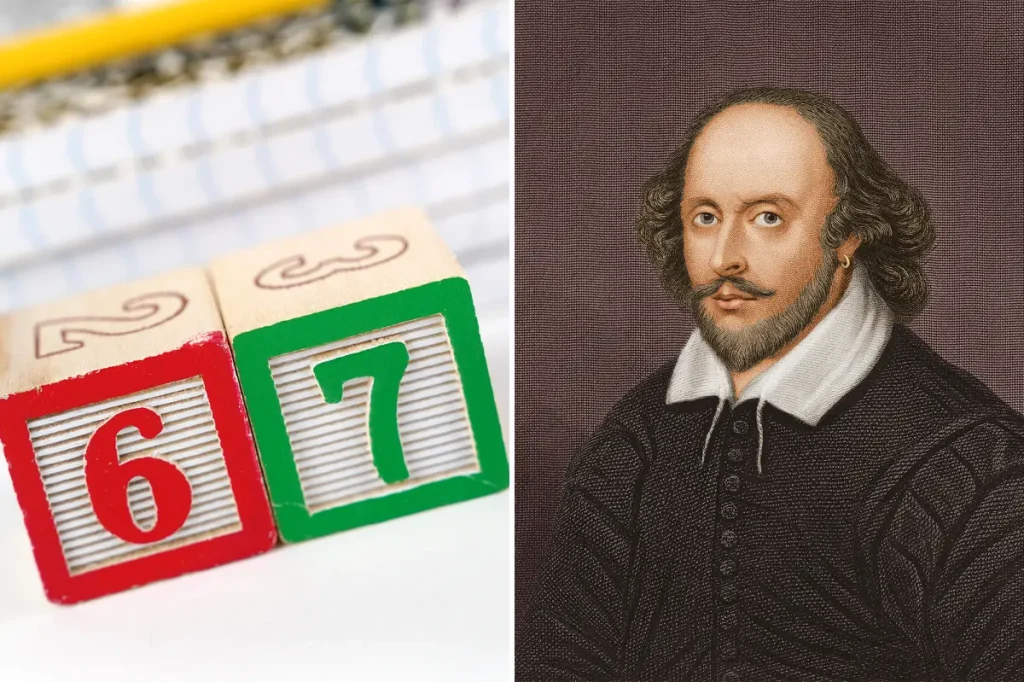

The historical lineage of this expression appears impressively distinguished if Marcus’s theory holds water. He points to evidence of the phrase in Geoffrey Chaucer’s works and, perhaps most notably, in William Shakespeare’s play “Richard II,” where the Bard wrote: “I should to Plashy too, but time will not permit. All is uneven, and everything is left at six and seven.” This Shakespearean usage seems to employ the phrase to convey a state of disorder or confusion. Marcus argues that this historical context actually aligns with the modern usage more than today’s youth might realize—the expression has long been associated with “risk, worry and confusion,” sentiments that might resonate with the uncertain navigation of adolescence and childhood social dynamics. The irony, of course, is that today’s young people employing the phrase are almost certainly unaware of this rich etymological backstory.

What we’re witnessing with “6-7” may represent a fascinating linguistic phenomenon where an ancient expression has been unconsciously revived and repurposed, divorced from its original context but perhaps still carrying some of its emotional undertones. Children and teenagers have always developed their own vernacular as a means of establishing group identity and distinguishing themselves from adults, but rarely does youth slang have such potential historical depth. It raises interesting questions about the cyclical nature of language and how expressions can fall dormant for generations before resurging in new contexts. The fact that modern kids use “6-7” without understanding its potential historical significance doesn’t diminish the phenomenon—it might actually make it more intriguing from a sociolinguistic perspective.

While parents and teachers might find themselves increasingly exasperated by the relentless repetition of “6-7” in their children’s vocabulary, there’s perhaps some comfort to be found in viewing it through this historical lens. Rather than dismissing it as merely “brain-rotting slang” without substance, we might appreciate it as part of the ever-evolving tapestry of language that connects us—however unwittingly—to centuries of linguistic heritage. And for the parents currently driven to distraction by this particular expression, history offers another consolation: like all slang trends, this too shall pass, eventually replaced by the next inexplicable phrase that will leave adults once again scratching their heads in bewilderment. Until then, the playful “tickets” issued by understanding police officers and the good-humored exasperation of parents form part of the timeless dance between generations, each developing their own linguistic markers of identity and belonging.