From Script to Screen: Anthony Hopkins’ Journey as Hannibal Lecter

In his newly released memoir, “We Did OK, Kid,” Sir Anthony Hopkins offers a fascinating glimpse into his experience portraying one of cinema’s most chilling villains, Hannibal Lecter in “The Silence of the Lambs.” At 87, Hopkins reflects on the role that not only earned him an Academy Award but also cemented his place in film history. His recollections reveal not just the making of a memorable performance, but the personal insights and creative instincts that brought this complex character to life.

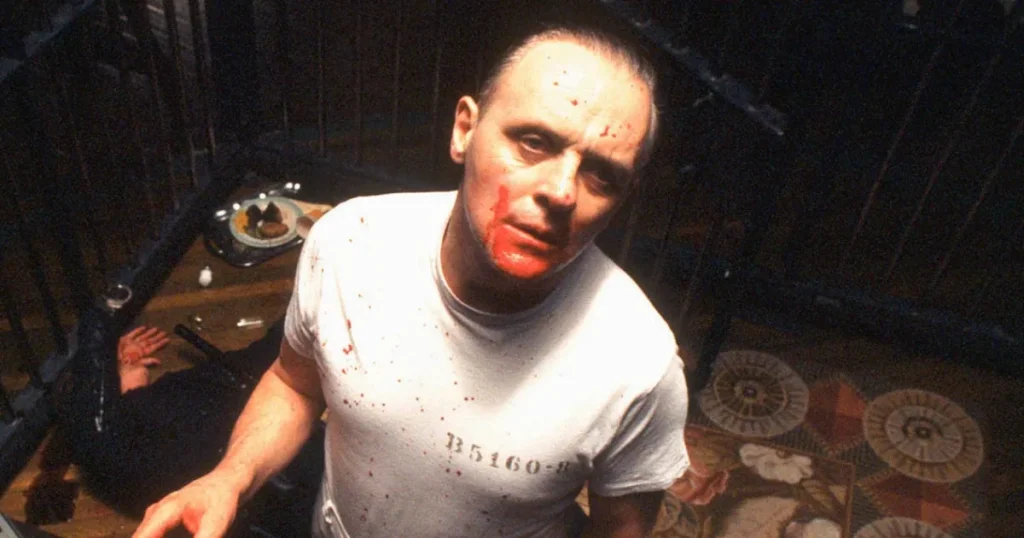

Upon first reading the script, Hopkins experienced what can only be described as an actor’s moment of clarity – an instant connection with the character that would define much of his career. “When I read those lines, I knew the character instantly. The pattern of his personality clicked in my mind,” he writes. Rather than leaning into the obvious monstrosity of Lecter, Hopkins made the crucial creative decision to play against type, opting for a “quiet, friendly version” of the killer. This counterintuitive approach – portraying a notorious serial killer with charm and sophistication rather than overt menace – is precisely what made his performance so unnerving. Hopkins tapped into a profound psychological truth: true evil often presents itself not as obviously monstrous, but as disarmingly personable. “I have the devil in me. We all have the devil in us. I know what scares people,” he confesses in his memoir, revealing how he accessed the darker aspects of human nature to inform his portrayal.

The physical embodiment of Lecter came from an unexpected source – Hopkins’ childhood fear of spiders. He recalls a formative memory from his father’s bakery, where encountering a large spider produced a visceral reaction. “One night I switched on the light in my father’s bakery, and right next to the switch was a huge black spider – patient and still, yet completely alert at the same time. I almost jumped through the roof,” he writes. This image – of something simultaneously motionless yet intensely present and threatening – became the blueprint for Lecter’s demeanor. Hopkins transformed this personal fear into Lecter’s predatory stillness, creating a character who, like the spider, could remain perfectly composed while radiating danger. Despite his confidence in his approach to the character, Hopkins initially harbored doubts about his suitability for the role based on his Welsh background, even asking director Jonathan Demme if he’d prefer an American actor. Demme’s bemused response – “Don’t you want to do it?” – reassured Hopkins, who by then had already developed a clear instinct for how to bring Hannibal to life.

The dynamic between Hopkins and his co-star Jodie Foster, who played FBI agent Clarice Starling, was marked by a deliberate distance that ultimately enhanced their on-screen chemistry. Hopkins recalls that from the very first table read, his interpretation of Lecter had a powerful effect on Foster: “A couple of seconds after I started to speak as Lecter, I saw Jodie grow tense. She later confirmed that she had been petrified.” This initial tension established a creative boundary that persisted throughout filming. The physical constraints of the set design – particularly the glass-box cell that separated their characters – further reinforced this distance. “It took about 20 minutes to get me in and out of that set, so I wasn’t really able to chat with Jodie or anyone else in those times,” Hopkins explains. The technical requirements of shooting their interactions through glass meant they often worked separately, filming their respective sides of conversations on different days, which naturally limited their personal interaction during production.

Despite this professional distance, Hopkins and Foster eventually shared a meaningful connection during a lunch break. In a moment of vulnerability, Foster confessed her fear of Hopkins – or more accurately, of the character he was portraying with such convincing menace. Hopkins, in turn, admitted his own intimidation by Foster’s talent and presence. This mutual acknowledgment culminated in “a big hug” that broke the tension between them. Hopkins notes that since that moment, they have “always greeted each other with great warmth,” a testament to the respect that emerged from their shared experience creating such intense, psychologically complex characters. Their limited interaction during filming, rather than hindering their performances, may have actually enhanced the authenticity of their characters’ relationship – the wary FBI trainee and the manipulative killer who develops a strange fascination with her.

Perhaps one of the most surprising revelations in Hopkins’ memoir is his attitude toward the acclaim that followed his performance. Despite creating what would become one of cinema’s most iconic villains, Hopkins was so convinced he had no chance of winning an Academy Award that he attempted to avoid attending the ceremony altogether. He eventually relented out of a sense of professional obligation, only to find himself called to the stage to accept the Oscar for Best Actor. “I remember getting up onstage. Kathy Bates handed me the Oscar. Apparently I gave a speech,” he recalls with characteristic humility. The disorienting experience of public recognition – “Questions by journalists. It all went well. I’d made it through with little or no anxiety” – stands in stark contrast to the meticulous control and awareness he brought to his portrayal of Lecter. This disconnect between the mastery of his craft and his modest self-assessment offers a glimpse into the mind of an actor who, despite his extraordinary talent, remained somewhat detached from Hollywood’s validation – perhaps another trait that allowed him to bring such authenticity to characters who exist on society’s margins. Through his reflections in “We Did OK, Kid,” Hopkins provides not just a behind-the-scenes look at a cinematic classic, but a masterclass in the psychology of performance and the personal experiences that shape an actor’s creative choices.