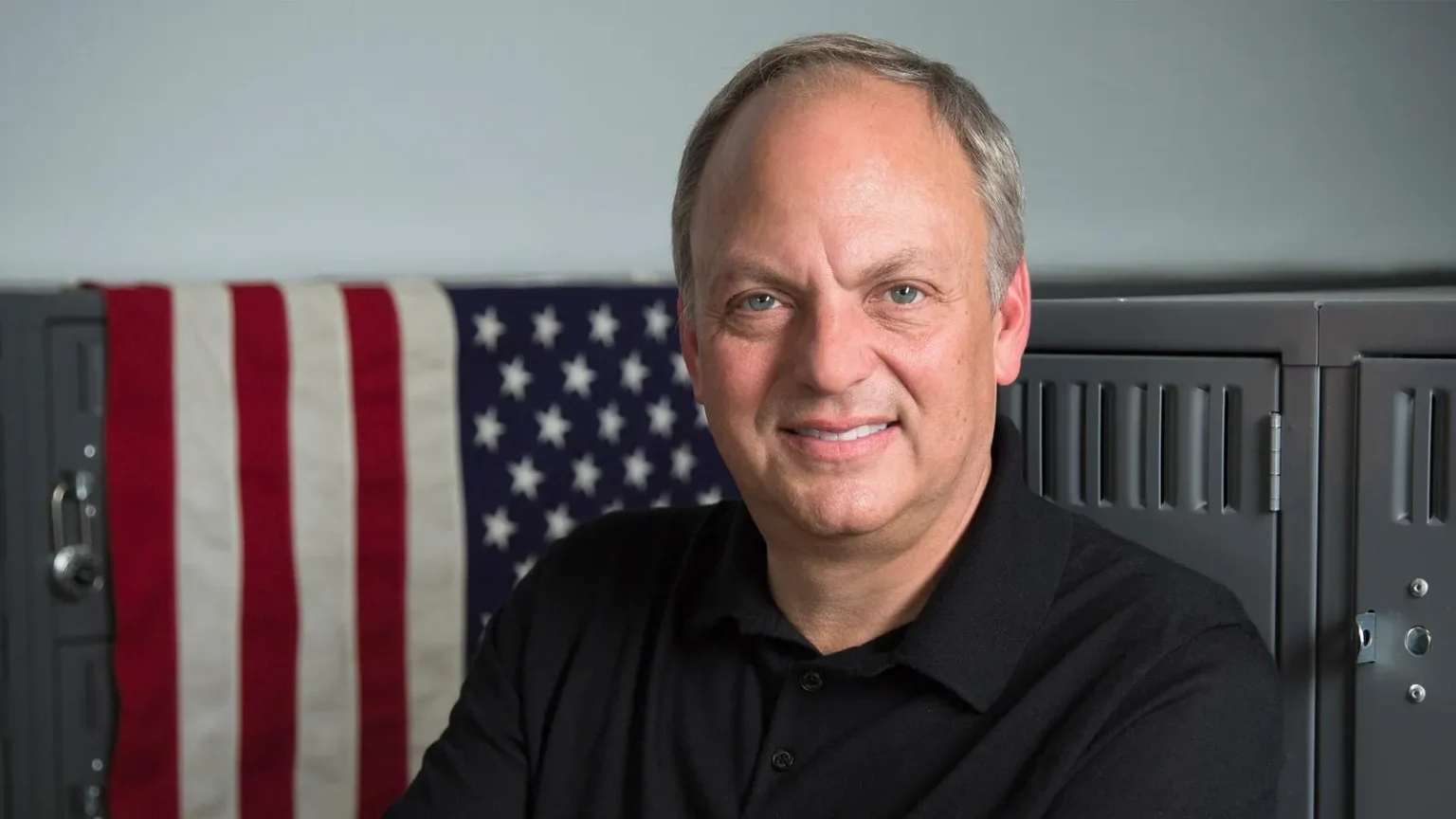

David MacNeil: The Patriotic Entrepreneur Nominated for the FTC

David MacNeil, founder of the $800 million revenue company WeatherTech, has built his business on a simple yet powerful principle: American manufacturing matters. In a December phone call with Forbes, MacNeil passionately argued that consumers are being “deceived and cheated” by online retailers not disclosing where products are made—an issue he believes requires urgent regulatory attention. This advocacy for transparency in country-of-origin labeling isn’t just business for MacNeil; it’s personal. His commitment to American manufacturing has now caught the attention of President Trump, who recently nominated the Mar-a-Lago member to fill one of three open spots on the Federal Trade Commission. If confirmed, MacNeil—whose net worth Forbes estimates at over $4 billion—would join the elite group of billionaires serving in Trump’s government, becoming the 12th such appointee.

Long before “Made in America” became a political rallying cry, MacNeil was building a manufacturing powerhouse on U.S. soil. He began selling American-made merchandise in 1994, just as NAFTA was ushering in an era of offshoring. Today, WeatherTech operates 11 factory facilities in Illinois, sources all materials domestically, and maintains remarkable vertical integration—from extruding its own plastic to cooking food for employees in-house. “We are so vertically integrated, we cook our own food for the employees. We cut our own lawns,” MacNeil explains. His commitment to domestic production has been showcased on billboards, in Super Bowl advertisements, and even at a donor lunch with Trump before his first election. When Trump questioned why he didn’t manufacture in China to increase profits, MacNeil responded, “It’s more important to provide jobs to my fellow Americans than it is to make another buck supporting Chinese manufacturing.” Trump’s second-term tariffs have already given WeatherTech an edge over competitors who manufacture abroad, with the company gaining “a larger slice of a shrinking pie” according to MacNeil.

The success of WeatherTech has built MacNeil an impressive fortune. Beyond the company—valued at about $2.4 billion—he owns at least $320 million in personal real estate (mostly in Florida), a collection of about 350 cars worth over $400 million, and $90 million in aircraft that he largely pilots himself. Commercial real estate holdings in Illinois and Florida round out his portfolio. Tax filings leaked to ProPublica revealed MacNeil collected roughly $180 million between 2016 and 2018, though he says he began lowering his compensation in 2019 to reinvest in the business. MacNeil insists his success benefits more than just himself: “We have to maintain our industrial might. If we don’t have the ability to manufacture things, we’re lost as a society. We’ve become a country of services—people cutting lawns and cutting hair.”

MacNeil’s patriotic fervor makes sense when you consider his background. Born in Canada in 1959, he immigrated to the Chicago suburbs on a green card before his first birthday and was raised by his mother, who taught pediatric nursing and instilled in him a strong work ethic. His career path wound through jobs as a gas station attendant, taxi driver, machinist, car salesman, and eventually a VP of sales at auto engineering firm AMG before he opened his own classic car dealership. Cars have always been his passion—he bought his first vehicle in 1976 for $300, a two-door 1968 Chevy Impala with a fried engine that he repaired himself. The idea for WeatherTech came during a 1989 trip to Scotland, where MacNeil noticed the superior floor mats in his rental car. Despite his wife’s skepticism about his enthusiasm for “rubber floor mats,” he secured distribution rights from UK-based Cannon Rubber, mortgaged his house for $50,000 to buy his first inventory, and sold $30,000 worth in the first month by personally visiting dealerships and placing magazine ads.

The WeatherTech brand evolved significantly over the years. After parting ways with Cannon in 2007 over quality concerns, MacNeil began manufacturing his own products. Early marketing focused on the emotional connection people have with their vehicles—”when somebody buys a new car, anything that happens in that new car is a tragic event,” explains former ad executive Dave Sollitt. The company’s first television commercials showed relatable messes like spilled coffee and muddy paw prints, driving sales up 250% in initial markets. In 2014, MacNeil gambled $4 million on WeatherTech’s first Super Bowl ad, reasoning that “if you’re going to become a household name, you need to be in every household.” The product line expanded beyond auto accessories to include indoor mats, boot trays, coasters, tablet holders, and even pet bowls—the latter designed after MacNeil learned some imported feeders contained radioactive material. Today, WeatherTech spends over $100 million annually on marketing, including prominent Chicago billboards and Super Bowl ads featuring American imagery and MacNeil’s beloved dogs. The approach has worked: Brand Keys ranked WeatherTech as the 24th most patriotic brand in America last year.

MacNeil’s FTC nomination raises questions about potential conflicts of interest, particularly regarding his advocacy for country-of-origin labeling rules that would benefit WeatherTech. The commission can prosecute companies for falsely claiming U.S. origins and could shift resources toward enforcement priorities that align with MacNeil’s interests. Ethics experts suggest he should recuse himself from matters directly affecting WeatherTech or involving his previous lobbying efforts. MacNeil himself seems unconcerned: “I won’t do anything that won’t benefit all people. I have no allegiance to anyone but the American people.” He plans to step back from day-to-day operations if confirmed and promises to recuse himself from potential conflicts. While he’s entertained offers for WeatherTech, saying “everything’s for sale except my dogs, daughter and wife,” he hasn’t actively sought buyers. For now, MacNeil is focused on the Senate confirmation process and the opportunity ahead. His journey from immigrant child to billionaire businessman to potential FTC Commissioner embodies a particular version of the American dream—one built on manufacturing, marketing, and an unwavering belief in American-made products.