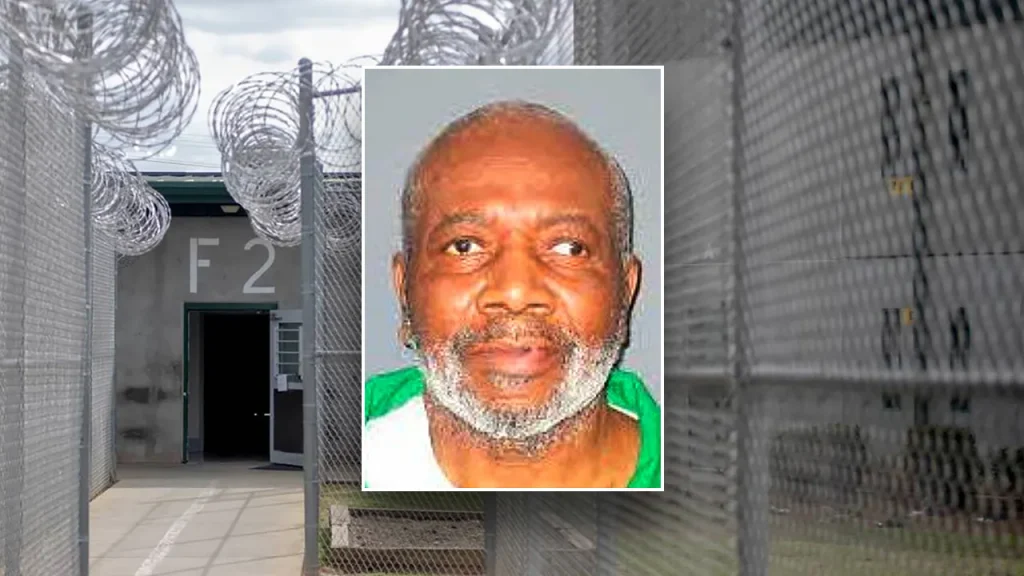

Death Row’s Longest Resident: The Story of Fred Singleton

In a quiet end to a complex legal saga, Fred Singleton, an 81-year-old man who held the somber distinction of being “South Carolina’s longest serving Death Row resident,” passed away from natural causes on Monday at the Kirkland Correctional Institution’s infirmary. The South Carolina Department of Corrections announced his death on Friday, closing a chapter that began nearly four decades ago. Singleton’s case had become a notable example of the intersection between mental health and capital punishment in America’s justice system, raising questions about competency, ethical treatment, and the purpose of the death penalty that remained unresolved until his death.

Singleton’s journey to death row began in 1982 with a horrific crime that shocked the small community in Newberry County. According to court records, he broke into the home of Elizabeth Lominick, a 73-year-old widow, where he raped and strangled her before stealing her jewelry. The evidence against him was substantial – his fingerprints were found on a bathroom window screen and inside Lominick’s car, which was discovered near where he was eventually arrested in Georgetown County. When police apprehended Singleton, they found Lominick’s diamond and gold rings in his pockets. The brutal nature of the crime, with Lominick being strangled with a bedsheet and discovered by her own sisters and niece, led to his death sentence in 1983.

What made Singleton’s case particularly remarkable was the legal limbo that followed. By 1993, the South Carolina Supreme Court had reached a complex decision regarding his fate. The justices ruled that Singleton wasn’t competent to be executed because he didn’t understand the consequences of his sentence – he couldn’t comprehend that he might die in the electric chair and was only able to respond to his attorneys’ questions with simple “yes” or “no” answers. This mental incompetency created an ethical dilemma that the court attempted to navigate. Rather than commuting his sentence, they maintained his death sentence in case advances in psychology might someday improve his mental state. Importantly, they also ruled that he couldn’t be forcibly medicated solely to make him competent enough for execution – a decision that reflected the moral complexity surrounding capital punishment for individuals with serious mental limitations.

For the next three decades, Singleton remained on death row in a state of legal suspension – technically sentenced to die, but protected from execution by his own mental incapacity. His case exemplified the challenging questions that arise when the criminal justice system encounters individuals whose mental faculties may not align with the underlying assumptions of criminal punishment. Can a person truly be held accountable in the ultimate way if they cannot understand the nature of their punishment? Is the purpose of execution deterrence, retribution, or something else entirely? And how should the state handle cases where a convicted person’s mental state places them in a gray area between culpability and diminished capacity? Singleton’s situation provided no easy answers, and his natural death at an advanced age meant that these questions would remain theoretical in his particular case.

South Carolina’s death row population now stands at 24 men following Singleton’s passing. The state has recently resumed executions after a lengthy hiatus, carrying out two firing squad executions this year. In March, 67-year-old Brad Sigmon, who was convicted of killing his ex-girlfriend’s parents with a baseball bat in 2001, became the first person executed by firing squad in the United States in 15 years. The following month, 42-year-old Mikal Mahdi met the same fate after being convicted of the 2004 killings of an off-duty police officer in South Carolina and a convenience store clerk in North Carolina. These recent executions mark a significant shift in the state’s implementation of capital punishment, coming after years of challenges related to the availability of lethal injection drugs that had effectively halted executions.

Singleton’s death brings a quiet conclusion to a case that epitomized the complications and contradictions inherent in America’s capital punishment system. While some might view his natural death as a frustration of justice that denied closure to the victim’s family, others might see it as a merciful end that spared the state from the ethical quandary of potentially executing a man who couldn’t comprehend his own punishment. What remains clear is that Singleton’s nearly four decades on death row – without execution – represents an extraordinary liminal existence that few have experienced. His story, though ending with little fanfare in a prison infirmary, nonetheless illuminates the profound questions about justice, mercy, mental capacity, and punishment that continue to challenge our legal system and our collective conscience as we grapple with the most severe penalty our society imposes.