The Shifting Sands: U.S. Withdrawal and Iran’s Rising Influence in the Middle East

In a significant shift in Middle Eastern policy, the Biden administration recently confirmed plans to reduce American troop levels in Iraq, following a similar drawdown in Syria initiated under the Trump administration just six months prior. This evolving military posture, ostensibly justified by a diminished ISIS threat and growing domestic pressure to end “forever wars,” has raised serious concerns among security experts about the power vacuum it may create—and who stands ready to fill it. At the center of these concerns lies Iran, a regional power that has spent decades meticulously expanding its influence throughout Iraq and Syria, creating what experts describe as a “shadow empire” that transcends traditional borders.

The relationship between Iran and Syria dates back to the 1980s, long before the Syrian civil war erupted. According to Gregg Roman, Executive Director of the Middle East Forum, Iran has transformed decades of diplomatic relations into a sophisticated enterprise that extends far beyond conventional military presence. Through its Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), Tehran has constructed a “parallel military infrastructure” across Syria, effectively turning the country into an “Iranian forward operating base.” This infrastructure isn’t limited to underground tunnels and weapons depots; Iran has embedded itself deeply into Syrian society through integrated systems that blend military operations with civil programs. Perhaps most concerning is the command structure Iran has established, which transcends traditional borders by integrating Iranian, Lebanese, and Iraqi commanders into a cohesive network that operates with remarkable efficiency across multiple countries.

The collapse of Bashar al-Assad’s regime in Syria in December 2024 and the subsequent takeover by Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HST)—a Sunni paramilitary organization once designated by the U.S. as a terrorist group with al-Qaeda connections—has complicated the regional dynamic but hasn’t necessarily diminished Iran’s influence. In fact, security experts warn that without a unified government in Syria, Iran is well-positioned to exploit the fragmentation and continue expanding its regional interests amid a complex geopolitical landscape where Israel, Turkey, and Russia are all competing for influence. Roman points out that if HST, in coordination with Kurdish forces in the northeast or the Druze in the southwest, fails to create a “bulwark” against Iranian influence, Tehran could strengthen its shadow empire even further. What’s particularly alarming is the precedent Iran has established—a template for building parallel military infrastructure that operates independently of host government control while maintaining strategic capabilities despite international scrutiny, a model that could be replicated elsewhere in the region.

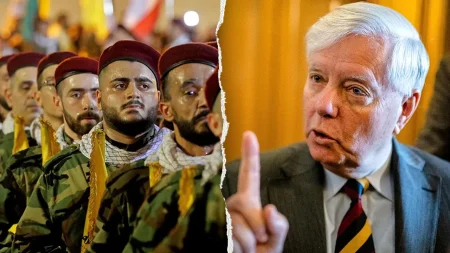

Iraq presents another theater where Iran has masterfully exploited power vacuums to extend its reach and counter U.S. influence. According to Bill Roggio, terrorism analyst and senior editor at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies’ “Long War Journal,” Iran’s strategy in Iraq is both effective and multifaceted, utilizing military, political, and economic means to achieve its goals. “There are hundreds of thousands of Iran-backed militants in Iraq,” Roggio explains, many of whom belong to the Popular Mobilization Forces—officially part of the Iraqi Armed Forces under the prime minister’s command, but heavily influenced by Tehran. These forces played a crucial role in fighting ISIS, giving them legitimacy while allowing Iran to maintain significant control. Beyond military influence, Iran-backed groups “wield significant influence in the Iraqi government” and “occupy a large, dominant block in the Iraqi parliament,” according to Roggio. Additionally, these militias possess considerable economic power, following a model similar to Hezbollah in Lebanon, with the ultimate aim of becoming analogous to the IRGC in Iran—a parallel power structure that serves Tehran’s interests.

Both Roman and Roggio express profound concern about the withdrawal of U.S. troops from the region and, more significantly, the diminishing American influence at a time when Iran is actively working to counter Washington’s interests. “We haven’t learned the lessons of Afghanistan and even the lessons of Iraq,” Roggio laments, arguing that the focus on troop numbers misses the more important questions about America’s mission in Iraq. “Is it a counter-ISIS mission? Is it a stave off Iranian influence mission?” he asks, questioning whether the U.S. has “the right mixture of military and diplomatic and political and economic influence in Iraq to achieve those goals.” The experts suggest that America’s approach to Iran has been consistently inadequate across both Republican and Democratic administrations, failing to recognize the seriousness and persistence of the threat Tehran poses.

The fundamental mismatch in strategic timelines presents perhaps the most concerning aspect of this geopolitical chess game. “The Iranians are patient. They’re operating on timeframes of decades and generations. And we aren’t patient. We operate in timeframes and two and four-year election cycles,” Roggio observes. This strategic patience allows Iran to pursue long-term objectives while the United States shifts policies with each administration. Iran’s ultimate goal, according to security experts, is to drive the United States from the region entirely, creating space to expand its influence throughout neighboring countries—from Afghanistan and Iraq to the Gulf states. As American forces draw down in both Syria and Iraq, the question remains whether U.S. policymakers fully understand the consequences of creating power vacuums in regions where Iran has demonstrated both the capability and determination to establish dominance, potentially reshaping the Middle Eastern landscape for generations to come.